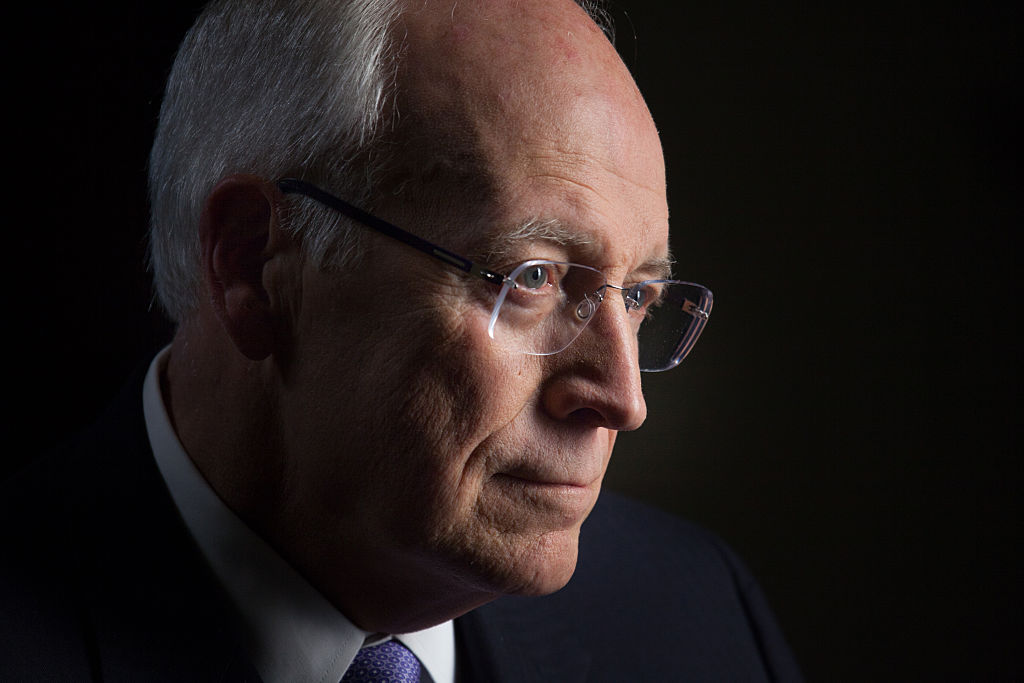

He was the peanut farmer from Georgia who rose to become the leader of the free world. Jimmy Carter, who has died at the age of 100, served as president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. While his term in office was not a success, his post-presidency — the longest in American history — was unparalleled in its public service. Uniquely among America’s modern leaders, he will be remembered more for what he did after the White House than what he did in it.

Carter’s long life was characterized by service: service to country as a decorated lieutenant in the US Navy just after World War Two, service to God as a Baptist Sunday school teacher in his hometown of Plains — and then service to government as a Democratic state senator, governor and finally president. But it was his later service as a statesman, post-presidency, that won him most plaudits. Shunning offers of corporate directorships and lucrative speaking engagements, he preferred to dedicate his life to advancing human rights abroad via the Carter Center which he founded in 1982.

For the last four decades of his life, Carter undertook numerous philanthropic and diplomatic pursuits. These ranged from building homes in Georgia with Habitat for Humanity to negotiating with the North Korean dictator Kim Il-sung as part of a peace mission in 1994. The Carter Center meanwhile worked to eradicate diseases and oversee free elections in countries around the world. These included the parasite guinea worm, which Carter swore to destroy. In 1980 there were 1 million reported human cases across the world; last year there were just four. For these efforts Jimmy Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002.

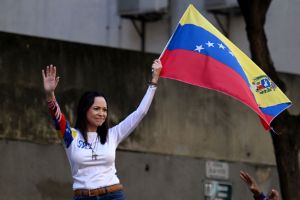

After leaving office, Carter regained much of his popularity

As president, some felt he deserved to win the award twenty-five years earlier, for his leading role in the Camp David Accords in 1978. The agreements between Israel and Egypt represented Carter at his best: thoughtful, dedicated, engaged and brave. His endeavors sustained twelve days of talks between Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin, leading to an historic breakthrough ending three decades of conflict between the two nations. Carter was credited with saving the summit on several occasions when it looked certain to collapse, citing passages from his annotated Bible and arguing passionately late into the night.

That personal triumph was a rare high point during Carter’s troubled four-year term in office. Elected in 1976 on a reformist platform, the 39th president sought to “clean up Washington” in the aftermath of the scandal-ridden Nixon administration. However, Carter’s tenure was marked by continuing recession, with inflation reaching a peak of 13.5 percent in 1980, virtually dooming any chances of a successful reelection. His presidency coincided with a major oil crisis that saw the price of gasoline double, sparking long lines of angry motorists at gas stations.

Domestic strife was accompanied by drift abroad. The American embassy in Tehran was stormed in November 1979, holding sixty-six Americans captive. The thirteen-month stalemate and a failed rescue operation left Carter looking weak and ineffective, with the prisoners only being released once he had returned to private life. Seven weeks after the hostage crisis began, the Soviet Union marched into Afghanistan, signaling the end of the détente period in the Cold War.

Burdened by economic woes and international decline, Carter faced an uphill struggle in the 1980 election to retain the presidency. His Republican opponent Ronald Reagan quipped: “Recession is when your neighbor loses his job. Depression is when you lose yours. And recovery is when Jimmy Carter loses his.” The voters evidently thought the same as Reagan won the election by a landslide, taking forty-four states to Carter’s six. Several key initiatives associated with the Reagan presidency — like deregulated air travel and Paul Volcker’s tenure as Fed chairman — began under his predecessor.

After leaving office, Carter regained much of his popularity through his philanthropic efforts. Such was his longevity that he outlived not one, but two of his obituary writers, at both the New York Times and the Washington Post. He returned to the home in which he had been raised, a tiny circle of Georgia farmland, a mile in diameter, alongside his wife of seventy-seven years, Rosalynn. Asked in one of his last interviews whether there was anything else he wanted in life, he replied simply: “I can’t think of anything. We feel at home here and the folks in town, when we need it, they take care of us.”

Leave a Reply