This is my second Christmas as a Christian. As an atheist, I had dismissed the bright lights and customs of Christmas as traditions that had evolved to keep our spirits up as the cold of winter creeps in. But the more I learn about, and participate in, the rituals of my adopted faith, the less Grinch-like I become. Christmas isn’t just crass commercialism, it’s vital to a western revival. Celebrating it is more important than ever.

The date of December 25 was significant before the birth of Christ of course. It coincided with the Ancient Roman celebration of Winter Solstice, just as March 25 was the Spring Equinox. The twenty-fifth was also, as of 274 AD, the Roman holiday Sol Invictus — the celebration of the rebirth of the sun, which lasted until the Emperor Constantine enshrined Christianity as the religion of Rome in 313 AD. Constantine also set the Christian Sabbath on a Sunday — the day of the Sun. Sol Invictus followed Saturnalia: the week of festivities celebrating the Roman god Saturn.

Atheists would say this proves that Christianity is just one among many competing superstitions. But just because Christianity has its roots in our political and philosophical traditions doesn’t make it false. Ritual is important. A decorated tree, the exchanging of gifts and a roasted goose are an excuse to gather the family around the hearth. In an age when family breakdown, divorce and single-motherhood is rife, a rekindling of that hearth helps heal our culture.

So do the stories of our faith. Jordan Peterson has written a new book about how the biblical stories informed all the assumptions upon which western liberal democracies rest. Our most important ideas — freedom of conscience, the presumption of innocence and forgiveness — are Christian innovations, so to celebrate Christmas is to celebrate both the reason of Ancient Greece and the moral law inscribed on the tablets given to Moses on Mount Sinai.

I hope I have imparted to my sons a love of my adopted spiritual home so that they are spared my wandering through the wilderness. But what is encouraging is that religious revival has taken root among the young. The New York Times has noticed that many American white men are returning to Church, which makes sense. Young white men are the public enemy number one of identity politics. They have the most incentive to look for alternatives to our current culture.

The greatest innovation of Christianity was to argue that all of us, Jew or gentile, were made in the image of God and could aspire to salvation. Isn’t it wonderful that so many people are being persuaded of that revelation? But more must be done to persuade young women also to return to the Church. Without their equal participation, congregations will wither and die.

Unlike Christianity, the politics of resentment has no doctrine of human dignity. It encourages you to dissolve the bonds of family and faith in favor of freedom; to consume and seek pleasure without responsibilities. Liberalism, when it ditches the guard rails of classical philosophy and Christianity, becomes hedonism, nihilism and misery. When faced with that prospect, the wisdom of the past seems like a much more attractive alternative.

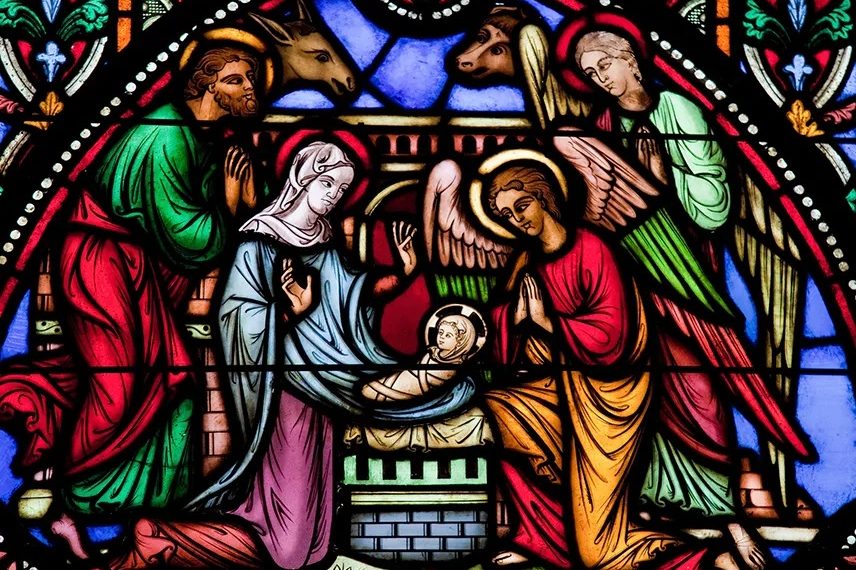

I have not become a Christian because I want others to abide by its ethics. I have become a Christian because the way it leads to a more well-rounded, fulfilling family life is so self-evident that there must be something more to it, something that can overcome our modern doubts. Whether in the Nativity scenes I visit with my children, or in the Evensong services we attend, I am participating in something transcendent, something that secularism can never offer.

Even Richard Dawkins, the hardest-hearted of atheists, has admitted that the songs, sights and sounds of this time of year move him deeply. Perhaps they will move him to join in the renewal of the western spirit too. Christmas is, after all, a time for miracles.