This Christmas, a Royal Navy Trident submarine will be quietly prowling the seas as part of the Continuous At Sea Deterrent mission. She will have slipped out of HM Naval Base Clyde in Scotland in late August. Her location is a secret, known only to a handful of officers aboard. Even the highest ranks of the navy, such as the chief of defense staff and the first sea lord, remain unaware of where their “bomber” is. For the rest of the crew, the submarine’s whereabouts are a mystery, with only the temperature of the water against the hull offering them a vague sense of geography.

One captain opened a present from his wife only to discover she had given him a nose-hair plucker

For more than fifty years, the Silent Service has been safeguarding Britain’s national security, usually unnoticed and unsung. But on Christmas Day, it’s worth remembering those who are far from home, lurking beneath the waves, ensuring our safety.

Navy submariners are a unique breed — wily, resourceful and rebellious. When an admiral once likened them to pirates, they embraced the comparison and began flying the Jolly Roger to mark operational successes, an unofficial tradition that persists to this day. These men and women, referred to as “sun dodgers” by their surface fleet counterparts, live a life like no other, with cramped quarters and long, intense watches.

Once submerged, the ship’s company follows a relentless schedule — six hours on duty, six hours off — around the clock. Roughly one third of the 100 to 135 men and women on board are asleep at any one time. The air inside is thick and fetid. After sea-riding in both attack and deterrent boats, I’ve concluded it’s a disturbing blend of hydraulic oil, sweat and the inevitable flatulence that accompanies a carb-heavy diet in which curry sauce plays a starring role. For submariners, food is more than just sustenance; it’s a morale booster, a small comfort in an otherwise grueling environment. Submariners rely on an unchanging weekly menu to tell them both what day it is and whether it’s light or dark above the waves.

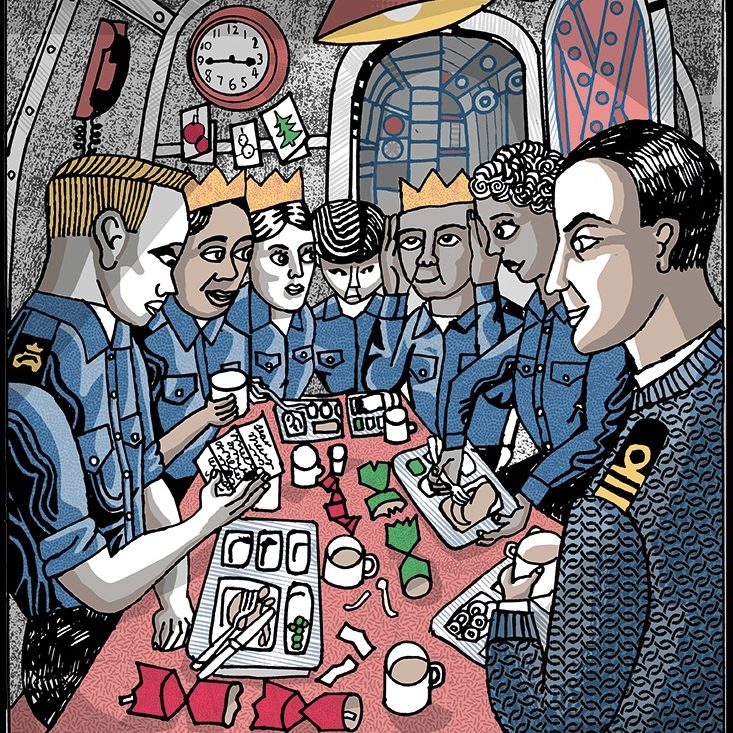

Ahead of Christmas, vast quantities of excellent “scran” (food) is loaded on to the submarine. On Christmas Day, it is a long-held naval tradition that the captain carves the meat — which might be pork, lamb, chicken or turkey — while officers serve the matelots. The head chef is likely to be discreetly rolling his eyes at the amateur meat hacking. Though alcohol is off-limits for the senior officers, sailors are allowed to indulge, albeit in strictly controlled amounts.

Christmas aboard a submarine is as festive as circumstances allow. All decide how they want to mark Christmas Day amid their usual workloads. Some submariners hold Mario Kart tournaments, while others transform spaces into makeshift cinemas, with screenings of submarine-themed films such as The Hunt for Red October. Christmas films tend to be vetoed for being far too emotional.

Communication with the outside world is severely limited while on patrol. Submarines cannot send messages for fear of revealing their position, but they can receive them. These are screened, coded and transmitted from the Northwood Headquarters to the boat, with the captain reading them first to shield the recipient from any potential bad news. Family deaths are only broken to the unknowingly bereaved as the boat sails back into the naval base, often months later.

Every sailor is entitled to receive one sixty-word “Familygram” message from ashore each week, which is doubled in length for Christmas. One humorous message received by a sailor was from his dog, which read “Woof, woof, woof” sixty times. Festive video messages are also allowed.

Given there’s no way Santa can squeeze down an optronic mast (periscopes are becoming passé), when a Christmas patrol is scheduled, submariner families fervently discuss where to source snowy cards and reindeer wrapping paper in high summer. Everyone does their best to send a bit of Christmas cheer in the form of compact presents like scratch cards or tiny Lego sets that can be built over weeks. Photographic cards are popular too, as they can be stuck on to the bulkheads above racks (bunks), adding to the sailors’ collections of family pictures.

Some submariners prefer to open their presents in private, finding solace in a quiet moment to reflect on what they’re missing back home. One captain opened a present from his wife in the wardroom only to discover that she had given him a nose-hair plucker. He was mercilessly reminded of this for the remainder of the patrol. A charity box of small presents is distributed to all on board and mess chiefs ensure that everyone has something to unwrap on Christmas Day.

Being at sea during the holidays is tough, both for the submariners and their families. One sailor, unable to be with his girlfriend, arranged a flower delivery service to present her with bouquets months after placing the order. He also bought her a handbag, which was stashed in his mother’s wardrobe all autumn before being produced with a flourish after the Queen’s speech.

Defending a maritime nation means the navy is on permanent high alert, even at Christmas. Not long ago, a hunter killer crew was activated to intercept a Russian submarine on December 23. Some 130 men swiftly converged at Devonport and were at sea within twenty-four hours in a Trafalgar-class boat, which has sophisticated passive listening devices fitted and small sensors pulled behind it.

While Christmas on patrol can be challenging, the camaraderie among the crew provides comfort. For these sailors, humor is an essential weapon in the face of adversity. When one captain announced they wouldn’t make it back for Christmas, one matelot quickly responded: “Thank fuck I don’t have to spend it with the mother-in-law!”

Though public recognition is rare for these covert operations and these sailors would never seek it, Christmas messages from senior officials, including the prime minister, first sea lord and fleet commander, acknowledge the sacrifices these men and women make. On Christmas Day itself, submariners speak of feeling utterly alone in the world, as they navigate through the inky darkness, imagining what their families are doing at that exact moment. It’s a time of profound isolation, amplified by the eerie silence of the deep, where the only sounds are the distant chatter of shrimp and the occasional whale song.

Nevertheless, it’s invariably standing room only in the Senior Ratings Mess for the non-denominational carol service. Carols are sung badly around a Christmas tree and the occasional tear is shed. When one crew forgot the music accompaniment CD, they simply decided to sing every carol to the tune of “O Little Town of Bethlehem.”

Leave a Reply