Money and power have rarely been strangers; often nations are made to shudder when the ruling elites battle each other. Britain’s late empire was divided between liberal manufacturers and aristocratic interests, whose conflicts hastened the rise of the Labour Party and the end of empire. In the United States, opposition to powerful trusts defined progressive politics for decades, ultimately laying the basis for the New Deal and a greater scope for government.

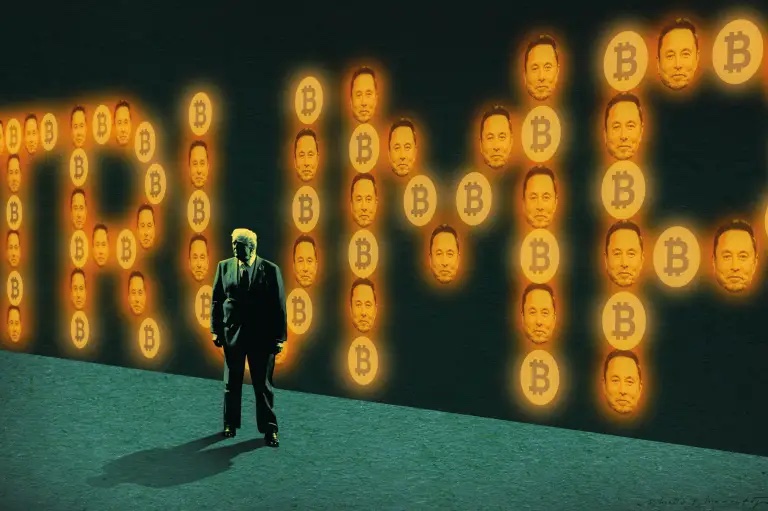

In the West today we are witnessing a similar divide among the uber-rich class — epitomized by Elon Musk’s embrace of Donald Trump — that is already reshaping politics. Until 2016 the US establishment, both Republican and Democratic, embraced similar views on national security, global trade and multilateral institutions.

But when Trump spoke against the uniparty’s dogma, many GOP backers on Wall Street and in corporate suites joined forces with the already left-leaning Silicon Valley oligarchs and Hollywood. Four years of Joe Biden’s remarkably inept administration broke up this united front, with even pro-Democratic power brokers like Chase’s Jamie Dimon praising Trump — something unexpected from the man Barack Obama saw as his favorite banker.

By the summer of 2024, Wall Streeters like investor Bill Ackman and certain prominent, formerly Trump-skeptical billionaires openly backed the Trump candidacy, joining existing allies like Miriam Adelson, Jeff Yass and Timothy Mellon. Energy executives, too, rallied to Trump. Some big backers like Harold Hamm and Kelcy Warren made their money in fossil fuels, as did the now president-elect’s proposed new energy secretary, Chris Wright. No doubt these executives are thrilled by Trump’s proposal to unleash American energy and boost their profits.

The biggest change took place in Silicon Valley; tech innovators, notes Tevi Troy in his illuminating The Power and the Money, long disdained politics as beneath them, but a rising tide of regulation ultimately forced them out of their open office spaces and into the first ranks of big donors. Elon Musk clearly sees steroid government as a barrier to his ambitions. This opinion is also shared by tech powers such as venture capitalists Marc Andreessen, David Sacks and Chamath Palihapitiya, who, along with Joe Lonsdale and Peter Thiel, have all jumped on the Trump train.

Democrats still rule in the tech world, but no longer exclusively. The divisions in tech break largely along functional lines. Big interests in software, social media, streaming and ecommerce generally favor Democrats, notably Alphabet, Meta and Microsoft, whose now retired founder, Bill Gates, kicked in a cool $50 million to Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign. They all profit from an ephemeral universe, where there are few blue-collar workers and no unions.

On the other hand, Elon Musk makes cars, spaceships and other products. As a manufacturer he needs reliable and affordable energy, flexible labor laws and ample physical space to develop. These are among the reasons he, despite the state’s unparalleled human capital, has pulled out of extremely regulated California. This industrial focus resonates with Trump’s appeal to blue-collar workers while the Democrats still win over the keyboard professionals.

Trump also wins backers in high-tech defense companies such as Palantir and Anduril that produce advanced weapons and technology perfect for the ramp-up of military and space-related spending which is likely to come about in the Trump budget. Their alliance with the new president may also give them leverage compared to the old, more Democratic-leaning big firms like the troubled Boeing, absurdly incompetent but reliant on DC connections. For Musk, a Trump presidency turns the solar system into his oyster.

Climate issues mark a key dividing line between the dueling oligarchs. Harris backers came heavily from the ultra-subsidized green industries, backers of steps like removing natural gas appliances and imposing EV mandates. (Ironically, Musk, easily the biggest EV producer in the US, appears on board with Trump’s rejection of them.) In trying to reach “net zero,” oligarchs such as Steve Jobs’s widow Laurene, Michael Bloomberg, the Rockefellers, Jeff Bezos and venture capitalist John Doerr seek to force the West to compete with more expensive, less reliable energy while China and other developing countries use coal, gas and oil to game the green future.

Trade is another dividing line; Trump’s tariff plans directly threaten firms and investors who make their fortunes shifting employment abroad. Biden, too, nudged policy away from free trade, but some hoped Harris would return to it.

These are the stark realities of our current gilded age. According to Pew, 80 percent of Americans believe wealthy donors have too much power, and they are right.

Of course, concentrated oligarchal power, whatever its political orientation, poses a profound threat to any real democracy. But it’s unsurprising to be treated to warnings in the predictably progressive, oligarch-owned Atlantic, that Musk’s backing Trump means “bending the knee” in a display of “strong man politics.” Apparently, when Harris scooped up big cash from Gates, LinkedIn’s Reid Hoffman, Salesforce’s Marc Benioff or George Soros, it was just rich guys acting for unselfish public reasons.

In the real world, outside the divergent political ecosystems, it’s important for Americans to take advantage of the emerging battle between oligarchs. If Trump doesn’t chase away his new backers with puerile outbursts, we could see a new, contentious era in elite politics, a marked improvement over the groupthink of the Biden years and a rare opportunity for the marginalized hoi polloi to force the oligarchs to compete for their favor.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply