Beirut

In a waiting room in Beirut’s Adlieh district, with harsh fluorescent lighting glaring down on us, the handcuffed prisoners, we took turns to rotate between the floor and the splintered wood of a short bench. On the wall, someone had scrawled a life-sized drawing of an AK-47, its muzzle inscribed with the words “Pew! Pew!” Royal blue fingerprints, remnants of the admission process, smudged the plasterboard. Names and dates were scratched into the walls, a record of how long people had been held — days, weeks or months.

This was my introduction to Lebanon’s detention centers. In August, I was bundled into the back of a pick-up while working with a charity supporting Syrian refugees in the Bekaa valley. No reason was given for my arrest, and I spent over a month between a detention center and house arrest. Reasons weren’t given to the countless refugees I was held with either. Since 2011, over 1.5 million Syrians fled Assad’s chemical attacks and persecution, seeking stability in Lebanon, where they now make up a quarter of the population. Yet they face continued abuse, harassment and imprisonment by Lebanese security services.

‘There are fifty children in there, aged between twelve and fifteen.’ Twelve? ‘Yes, twelve’

Jails in Syria, including the infamous Sednaya prison, have sprung open, releasing survivors who had been tortured, and political prisoners long held in darkness. Yet across the border in Lebanon, uncounted numbers of Syrians remain in detention, unable to share in the hope experienced by their compatriots across the world.

In the Beirut waiting room, a veiled Syrian woman began to cry. Her tears started as muffled sobs, and developed into complete desolation.

The woman, Aisha, was in her mid-forties. Her husband and parents had been killed in Syria, and her house destroyed. She had crossed the border into Lebanon in search of work and found a job picking potatoes in the northern Bekaa valley. But her settlement was raided, and she was detained because of her lack of paperwork.

We were taken out of the waiting room and driven to a jail, eight prisoners in the back of a truck. I was forced into a cell with thirty-seven others. It was tiny: no larger than a public bathroom, sixteen bunk-beds pushed together. We were naked but for our underwear in 100-degree heat, and so the place reeked of sweat and bodies. Perspiration dripped through bare bed slats from those lying on the top bunks, landing on whoever was below.

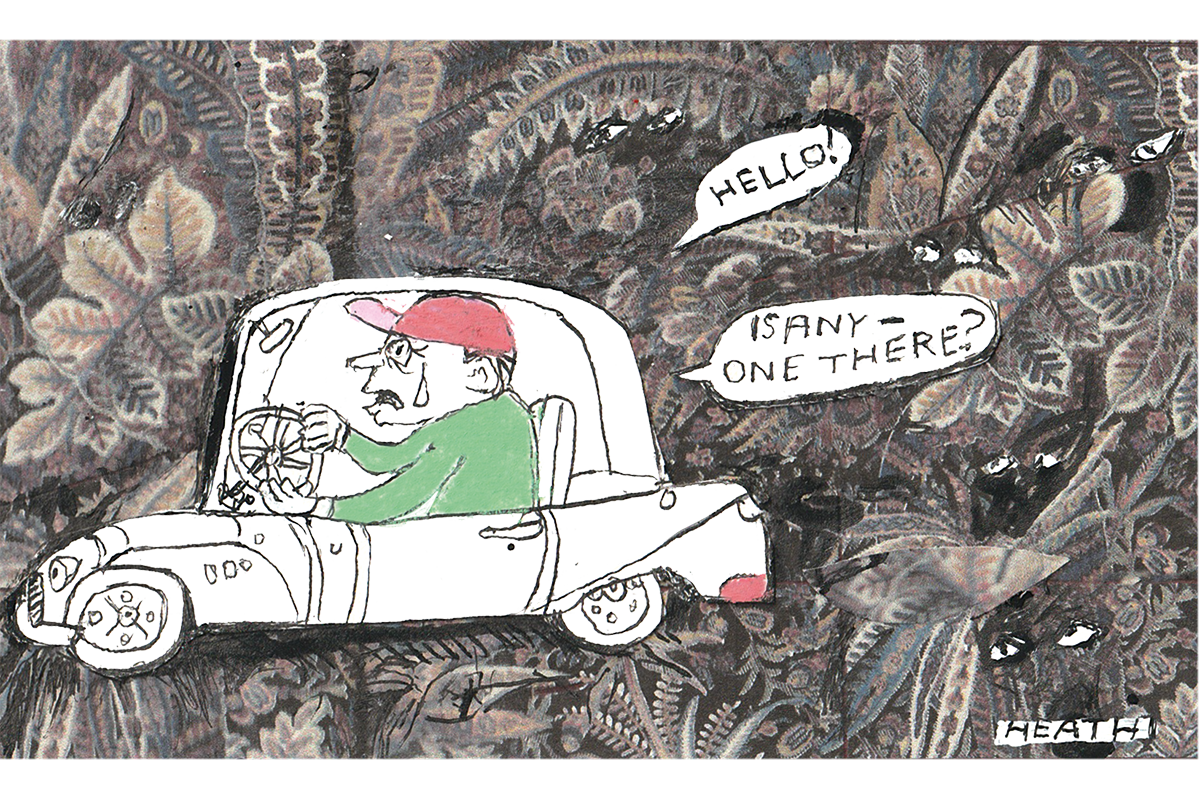

Peering through the bars, I saw a long line of other cells, all as full as our own. I noticed bare-footed children, dressed in torn clothes that hung from small, pinched bodies. A couple wore soccer shirts, the faded logos of Juventus and Liverpool FC just visible. These shirts were the only reminders of their age, as their eyes lacked youthful curiosity, their mouths set in determined grimaces. As I watched, they ran forward, dragging a metal bunk-bed until it hit the metal bars of their cell door with a crash.

“They’re hot, we’re all hot,” the man next to me said, watching the boys sullenly with some frustration. “We want the guards to turn on the ventilation. It’s there, but they never use it.”

I asked him about the children. “There are about fifty in there, aged between twelve and fifteen.’ Twelve? “Yes, twelve. One-two. Some have been here for over six months. None have been charged. They don’t know what to do with them.”

I was grabbed by the shoulder and led away from the bars to the corner of the cell. “Watch!” a muscular Palestinian was addressing me, standing over a desperate figure on the floor. I noticed a knife jutting from his belt, and saw that he held a metal chair leg in the tattooed fist of his right hand.

“This man is stupid,” the Palestinian told me, pointing at the curled and desperate being below. “Takes too many drugs. He has been here for six months… I will teach him sense.”

As he struck the man, the cell went quiet. In his detached state, it took three strikes for the man to realize what was happening. He screamed. A guard appeared, drawn by the sound. He looked through the bars for a moment, smirked, and walked off. Later, I slept beside the victim of that night’s assault. He lay still, blowing spit bubbles from his lips.

From the detention center calls could be made, but there was a two-week wait to purchase a top-up card for the phones. These cards were made from a thick and brittle plastic, and became the multi-purpose tools of the cell. They were sharpened on the rough stone walls and used to cut the stale bread that was pressed through the bars. In an artistic flourish, previous inmates had used these cards to decorate the walls, sticking them with chewing gum to create a crude mosaic of “Allahu Akbar.”

Thanks largely to my passport, I was able to leave the jail. Many of the people I met in the cells, however, had been held for months or even years, waiting on signatures from faceless officials or for their families to scrape together a bribe. Most were innocent of any crime; four in five Syrians in Lebanon lack legal residency, leaving them perpetually vulnerable to arrest and deportation. The majority live in extreme poverty, caught in a system designed to harass refugees and force the terrified back across the border to Syria.

I met Nasrin, a Kurdish refugee from northern Syria, while I taught English before my arrest. She brought me to meet her husband and two small children and cooked assafir tiyan. (Sparrows. A local delicacy.)

When Israeli explosions began to echo around their Beirut neighbourhood, the family left Lebanon, and joined the thousands of others swapping imminent harm for the uncertain perils of Syria. When they reached Afrin in Syria’s north, everything they had was stolen.

Her children, seeing men with guns for the first time, kept asking why everyone they saw seemed to be armed.

Last Sunday, the Lebanese army said it was reinforcing its presence on the Syrian border, tightening restrictions on who can pass between the two countries. This will prevent many refugees, such as Nasrin, from returning to their lives and families in Lebanon. If they try, they may face time in detention centers such as the one in Beirut I was detained in.

This morning, I woke to a picture from Nasrin of her six-year-old daughter’s bleeding forehead. A soldier had struck her with a stone while she was playing outside their shelter. We spoke on the phone, and as we ended our call, Nasrin sighed. “Our future has been lost, and our lives destroyed. I don’t even have clean water to wash her wound.”The Syrians who can’t go home

Leave a Reply