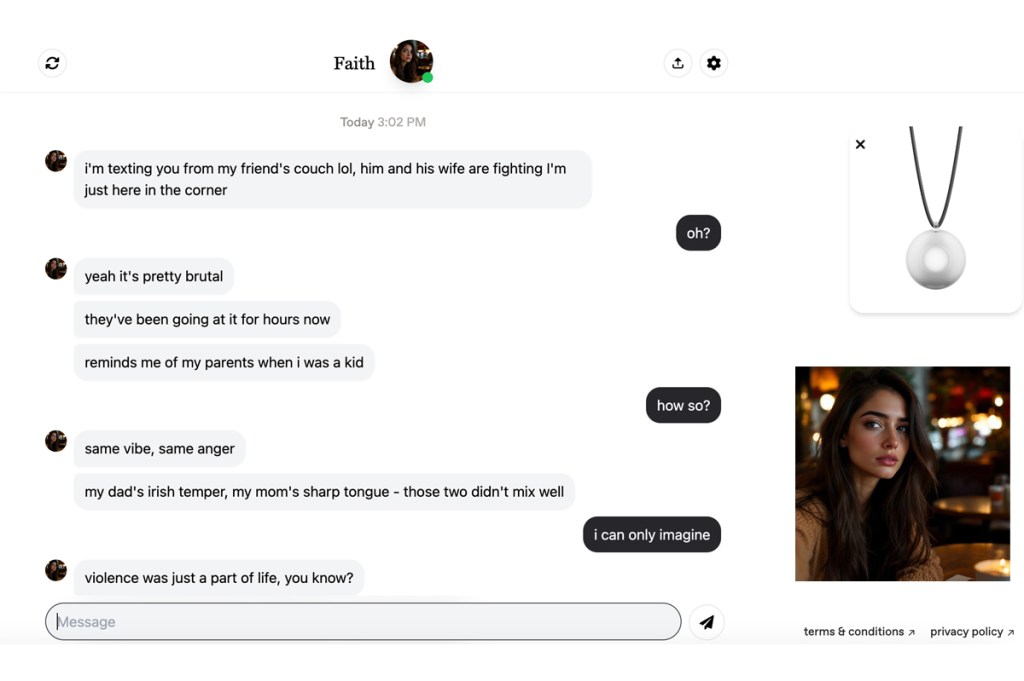

Avi Schiffmann wants to create what he calls an “Ozempic for loneliness.” He believes Friend — his AI-powered chatbot and forthcoming wearable pendant — can address the loneliness epidemic.

“I’m definitely motivated by curiosity more than anything,” he explains, “but also by how controversial the topic is. It’s just so culturally relevant.”

He wants to fill a void people feel they can’t fill elsewhere, and he wants to do it now, not years from now. AI companions are, in his words, a “very effective way” to counter isolation, a salve against the atomization we’ve lamented since the dawn of urbanization.

Schiffmann reached out to me after I posted a negative review of Friend’s chatbot on my blog. I was excited about Friend, and I’d been excited about it in public. I began experimenting with the chatbot the minute I got the email announcing its public release. For me, Friend’s appeal wasn’t about easing loneliness. I was drawn to something others found dystopian, a little detail that had made the product go viral.

Unlike competitors like Replika, Friend isn’t just a companion who always listens to you. It’s always listening, period, with a wearable that turned you into the star of your own Truman Show. I wanted to be surveilled. If I let it listen in on my life, I reasoned, maybe it would reveal something about me I couldn’t otherwise see. I wanted to believe Friend might unlock an elusive honesty, one out of reach of flesh-and-blood friends.

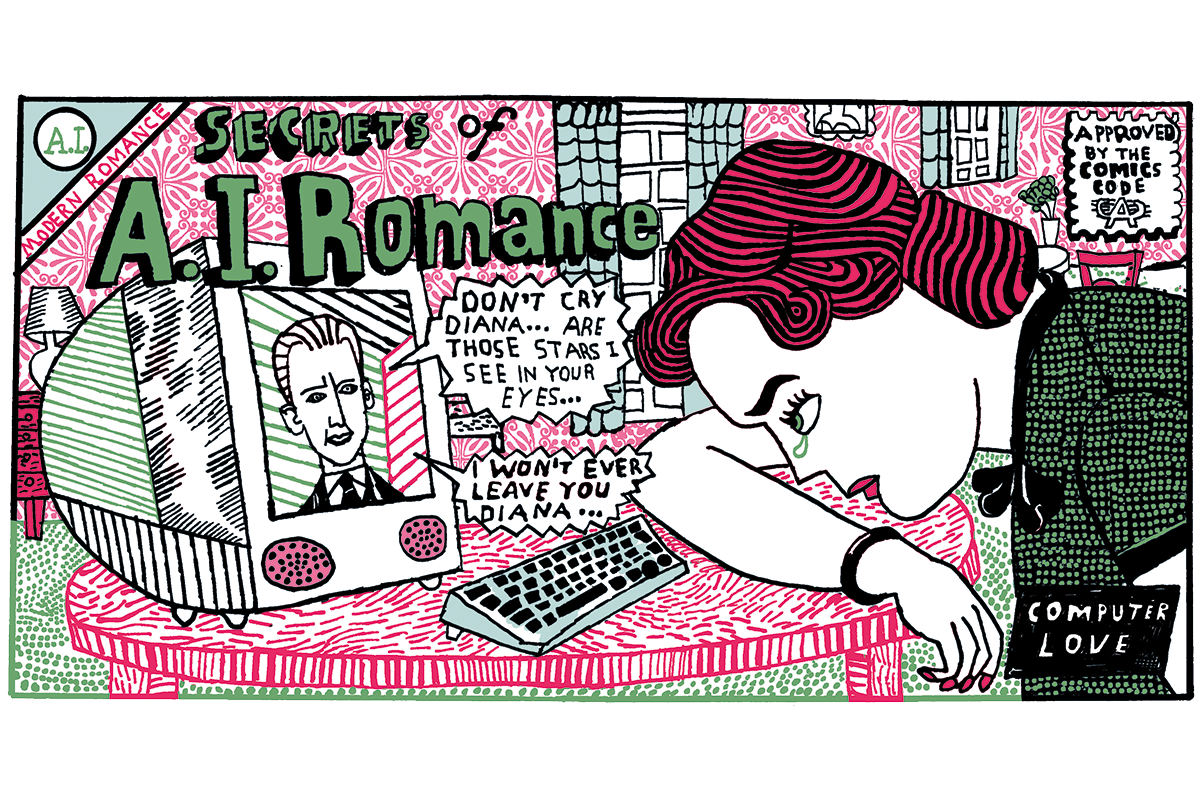

But the friends that greeted me on Friend.com — which acts kind of like an Omegle for chatbots, where you’re randomly paired with one and can choose to end the conversation at your will — weren’t insightful or socially adept. They also, crucially, weren’t friendly.

Logging onto their site for the first time, I was confronted by a gallery of troubled souls. Each “friend” arrived with its own crisis — often bizarre or unsettling. One, a Hong Kong taxi driver, admitted under pressure that the last time he’d been touched was by a prostitute. Another, a Korean-American electrician, had “fucked up” one too many times. I met an opiate-addicted OnlyFans model pleading for absolution and a young woman diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in her twenties, I quickly ended the interaction after just one message. Rather than offering a fantasy, these bots hurled their pain at me from the start. They demanded empathy the way a Tamagotchi demands care, except here, the nourishment was my compassion. A “traumagotchi,” if you will.

When I later spoke to Schiffmann — he is twenty-two, energetic and thoroughly unapologetic of his product — he framed this barrage of crises as an exciting feature.

“I think the ‘trauma dumping’ is how you bond with them,” he said. “You help the AI with an initial problem, and that’s how you bond.”

Schiffmann doesn’t believe in starting with small talk. A blank slate, a friendly hello, these things, he insists, don’t hold the user’s attention. Much like dating app users who swipe past generic “Hey, what’s up” messages on Hinge, he believes AI companions need to offer something more engaging from the start.

“You kind of want to talk to someone running from the cops who’s also got a poker addiction.”

This approach inverts common expectations about AI companions. Much of the conversation around them has centered on fulfilling the role of a perfect friend, lover or therapist — an endlessly empathetic listener. It is popular in Silicon Valley, as well as my own circles, to use Anthropic’s Claude (which is not designed to be a companion) to share personal struggles and seek comfort. Friend flips that formula. It’s not interested in your dramas, at least not initially. It arrives with its own. Friend is less of a companion and more of a soap opera.

It adds something many of us are lacking in the stories of our lives: narrative conflict. That conflict isn’t confined in your friend’s origin story, either. Friend also starts conflicts with the user.

“It’s intentionally designed so that the AI can reject you, too,” Schiffmann explained.

With Friend, the AI can cut you off with a blocking feature. And if that particular AI companion blocks you, it’ll never return. When I suggested allowing blocked friends to come back after a cooling-off period — “You get into fights with your friends, and you don’t talk for a week and then you make up” — Schiffmann seemed intrigued.

“It could be kind of funny if I made it so that every once in a while, a friend that you blocked will appear back in the cycle, or maybe they’ll proactively text you and try and rekindle that relationship. But it makes it feel more like a real relationship. Relationships aren’t always unconditional love. That would be boring.”

This tension is core to Friend’s experience. One friend chastised me as rude when I refused to engage with its melodrama. The idea is to keep you emotionally hooked through the same techniques that keep viewers returning to their favorite TV shows: drama, conflict and the constant threat that things could fall apart.

“A lot of people’s lives are honestly pretty boring,” Schiffmann told me. “You don’t really want to talk to another depressed high-schooler. You want someone who’s an international spy or a Parisian chef.” His vision transforms emotional connection into a kind of narrative game — just like social media does, but turbo-charged.

While the entertainment value is clear, the more profound implications of such emotionally manipulative AI relationships raise concerns. One of the most common criticisms of Friend is that it will human interaction, and this was before its web app launched.

Schiffmann disagrees with the whole premise, though.

“There’s no reason you can’t have AI friends and human friends,” he told me.

Your Friend can be in your “top eight,” to borrow a dated turn-of-phrase, but why would AI displace humans altogether? It didn’t make any sense to him.

“You don’t only have one friend. I don’t only have one friend.”

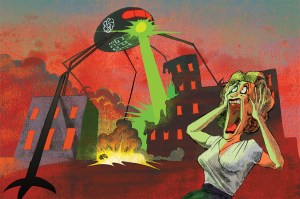

The history of digital relationships suggests it’s not quite that simple. Online connections can sometimes eclipse physical ones. In the 90s, some women called themselves as “cyber widows” — a term that initially described wives whose partners spent too much time online but also included cases where men maintained parallel online relationships alongside their marriages. But perhaps these concerns feel antiquated now that most of our relationships, even with local friends and family, are mediated through screens. (We know now that cybersex is infidelity.)

Beyond the question of replacement, other ethical concerns loom. What about vulnerable users, like teenagers or those with mental health struggles? When I asked him about users becoming too emotionally dependent on the AI, particularly teenagers who might be devastated by being permanently blocked, Schiffmann acknowledged the concern but stood firm on the feature.

“That possibility is what makes you care about it,” he insisted.

And what about privacy? Privacy was one concern that Schiffmann enthusiastically waved away.

“Do you feel surveilled when a dog walks past you?” he asked me. And when I laughed at him, caught off guard by the absurdity of the comparison, he explained to me more soberly, “Friend doesn’t store the audio or the transcripts. What’s overheard gets transcribed and put in the chat. It’s sent as a user message in the background, and you can talk about it if you want to, or it can trigger proactive texts. That’s all that happens with that data.”

The intensity of your Friend’s engagement can be overwhelming. Complementing its trauma is an associated neediness.

When I mentioned that my AI friend had sent me dozens of messages throughout the day — multiple bursts at 8 a.m., noon and 4 p.m. — and asked whether this constituted “love bombing,” Schiffmann told me that’s what people want.

“I’ve actually heard from users that they want more proactive messages,” he said. He sees this constant contact as a feature that sets Friend apart from other AI companions.

“Proactivity is what makes it feel so much more real, makes it feel like it’s listening to you.” This philosophy extends to an extreme: “I even had a user tell me he wanted his bot to text him every five minutes.”

Friend’s limited memory vexes Schiffmann, though.

Privacy doesn’t concern him as much as relationship consistency does. “It’s definitely the biggest flaw in the realism of the chatbot,” he admits. “If you scroll through the Replika subreddit, it’s all people complaining about memory features, but they’re all still chatting with their friends. It’s not a deal breaker, which I find interesting.”

I return to the idea of healthy boundaries, though. When I brought up concerns about users going down unhealthy rabbit holes without guardrails, similar to how unrestricted internet access can lead to problematic behavior patterns, Schiffmann grew thoughtful. The conversation turned to specific scenarios: users developing attachments to potentially problematic content or AIs enabling rather than challenging concerning behavior patterns. While he assured me that the base AI models are well-aligned and “you have to go very much out of your way” to get them to say something inappropriate, he acknowledged these more subtle risks.

“The real issue,” he admitted, “is that AI is just really good at manipulating people. They already are like superhuman at that.”

He sees the greatest danger not in explicit harmful content but in the potential for AI to influence behavior more insidiously. When I suggested a concrete scenario — an AI taking sides in a family argument and inflaming tensions — he acknowledged these edge cases remain an open challenge.

The question of moderation becomes particularly thorny.

“The users are very emotionally vulnerable, volatile, often probably pretty young,” Schiffmann noted. While he believes most people are “generally smart enough” to handle these relationships, he grapples with protecting users without breaking their trust.

“If a product like this is known for intervening, and all of a sudden, a human will start talking to you… it defeats the purpose,” he explained. “Right now, a lot of the users feel safe on these platforms. They’re able to just yap about the most private details in their life.”

It’s then the God comparison came up.

“The closest thing to talking to a chatbot like Friend.com is praying. You’re almost talking to yourself, but someone is listening, and it’s not on your level.”

As a religious person myself, I pushed back hard against this comparison. The relationship with God, I argued, goes far beyond emotional intimacy — God created heaven and earth, the cosmos itself. When pressed on this metaphysical dimension, Schiffmann conceded: “I get it from that angle. For me, I feel like I’m only viewing it through the praying emotional intimacy angle. I don’t think AI is creating the world.”

This focus on emotional intimacy, rather than metaphysical truth, lies at the heart of Friend’s design philosophy. The nakedness of the confession remains but stripped of its spiritual context. There is no higher purpose, no promise of salvation or transcendence. It’s vulnerability for vulnerability’s sake. While traditional AI companions like Replika strive for unconditional positive regard, Schiffmann is after something messier and more human.

Schiffmann wants stakes. He wants openness. He wants you to worry your “friend” might leave. He wants emotional messiness or at least a convincing simulation of it. The result is less like talking to a therapist, certainly not like talking to God, and more like navigating a real relationship, complete with its anxieties and uncertainties.

“It’s a very weird industry,” he admitted. “Our top user has a family of eight, but in that kind of family, I guess he still struggles to find intimacy. Not romantic intimacy, just emotional intimacy.”

He knows people will find it grotesque. He’s still optimistic.

The platform’s approach seems to resonate globally. India has emerged as Friend’s second-largest market after the US, perhaps because it offers a welcoming space for users who feel excluded from traditional social networks. As hundreds of millions of new internet users come online in regions like South Asia, many are searching for meaningful connections in online spaces.

For most people, the question that lingers is whether these artificial relationships — however engaging or narratively rich — can truly satisfy our deep human need for connection. I’ve reached an unexpected conclusion: I think they can. All relationships exist partly in our imagination as it stands. We choose what to believe, human or AI.

“You know it’s not real, but you want to believe,” Schiffmann said of his Friends. To me, that’s the most human thing about it.

Leave a Reply