“Brave Assad fled to Putin. Where will Putin flee?” asked Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky after the Syrian dictator escaped embattled Damascus for Moscow at the weekend. Assad was granted asylum in the Russia capital on the “humanitarian grounds” he had denied his own subjects for so long. But what kind of life is Putin offering him?

On the face of it, the answer is a rather opulent one, even if in practice it means becoming part of one of the most rarified zoos of all: Putin’s collection of ex-dictators. West of Moscow, a little way beyond the city’s MKAD orbital motorway along the A-106 Rublyovo-Uspenskoye Shosse, lies the village of Barvikha. From the main road, it is pretty undistinguished, but as soon as you head into the side streets, you notice the opulent dachas — mansions rather than summer cottages — behind high walls and ornate but very functional metal gates.

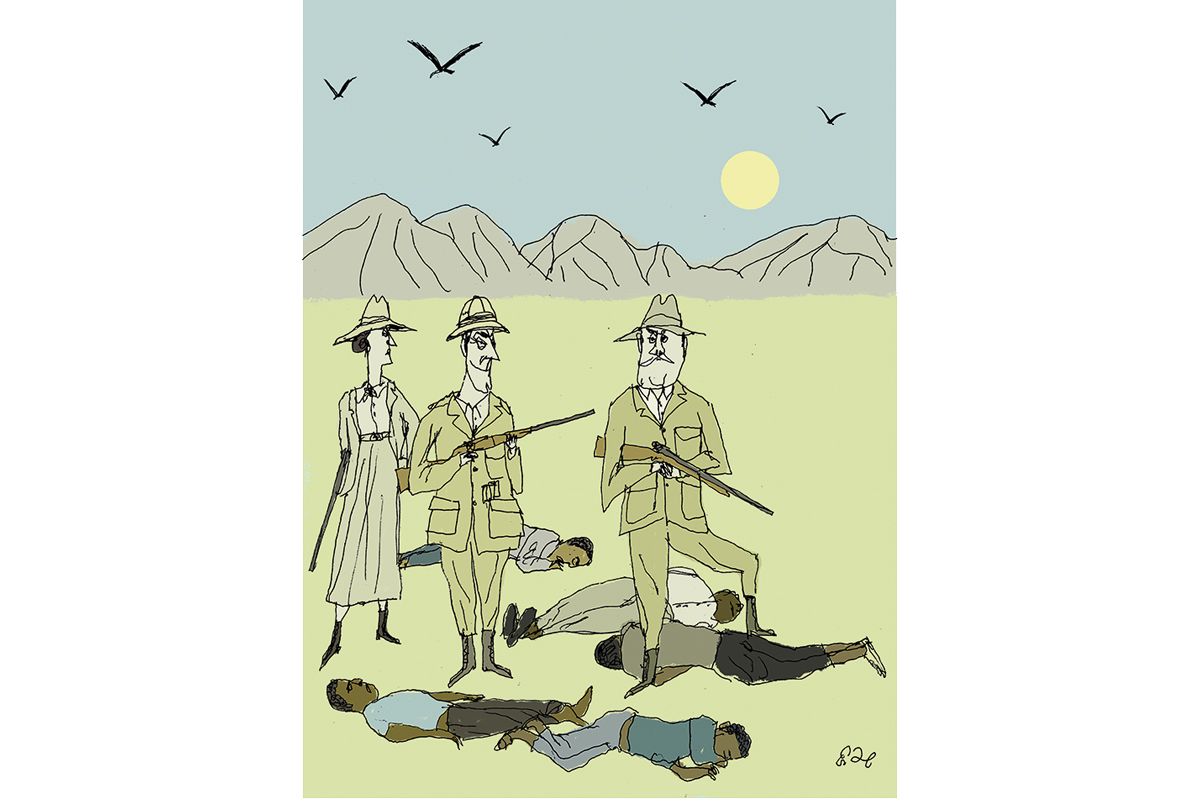

The new exiles will pay for their asylum by becoming wards and pawns of the Kremlin

In Soviet times, this was one of the select settlements of houses assigned to party figures and select members of the loyal cultural elite. Now it has become a home for the more tastelessly wealthy new rich, and a selection of deposed dictators and their families.

First, there is the family of deposed Serbian president and war criminal Slobodan Milošević. There are no fewer than three former presidents: Askar Akayev of Kyrgyzstan (overthrown by the 2005 “Tulip Revolution”), Aslan Abashidze of Georgia’s Ajarian Autonomous Republic (convicted in absentia on terrorism and murder charges in his native country), and former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych (who fled following the 2014 “Revolution of Dignity“). Bashar and Asma al-Assad are presumed to be the latest addition to the collection.

This is the most tastelessly gilded cage of all. The properties are massive (Yanukovych reportedly splits his time between a $52 million mansion in Barvikha and a place in Rostov region to the south). The village offers upscale restaurants and retail outlets to match, from the Drim Khaus (“Dream House”) shopping center to Barvikha Luxury Village, where you can pick up a Ferrari in your new Ermenegilda Zegna outfit.

However, the Assads will have to pay for it. Of course, no self-respecting dictator will not have salted funds away just in case. The US State Department has estimated the Assads’ private fortune at up to $2 billion secreted around the world in offshore accounts and shell corporations, although it is unclear how much of it they can still access. They will have to pay for the properties and the other trappings of wealthy exile life, not least the private security guards and the discreet servants. A fair number of the latter will likely be agents of the Federal Security Service (FSB).

The other way the new exiles will be paying for their asylum is becoming wards and pawns of the Kremlin. Bashar al-Assad is being reviled on Russian social media and official channels alike as having brought the collapse of his regime onto himself. Their argument is that he failed to take advantage of the window of opportunity provided by the 2015 Russian intervention either to reach some kind of peace accord with at least some of the rebels or build up his army. To a degree Assad makes a handy scapegoat, but in fairness this is not far off the mark: both Moscow and Tehran had become increasingly exasperated by his complacency before the recent reversal.

Nonetheless, Assad will have to grin and bear it if he wants to retain his freedom. Although there is little likelihood of him — or his twenty-three-year-old son Hafez, who had been groomed as crown prince — ever returning to Syria, he remains a potential bargaining chip. Putin is unlikely to hand him over to the Syrians, let alone a war crimes tribunal. In many ways, giving him asylum was the final contingency in Moscow’s social contract with its client-dictators: if all else fails, you’ll have a bolthole here.

Instead, the Assads must now do whatever is convenient for the Kremlin. For now, their job is probably to keep quiet and not remind the world that Moscow backed a leader who committed the cardinal sin of being both viciously dictatorial and unsuccessful. If in the future, there are talking points the Kremlin wants the Assads to recite, then they had better learn their lines and put their public faces on. They have all the security and luxury they can afford — and that the Kremlin is willing to grant them. Yet as more evidence emerges of the horrific crimes which took place in the bloodstained cellars of Sednaya prison, and footage of the serried ranks of the Assads’ luxury cars contrasts with the squalor in which so many Syrians were forced to live, it is unlikely anyone will feel sorry for them — and nor should they.