At the end of this month, one of the world’s most renowned scientists will send $400 to a charity to settle a wager with another of the world’s most renowned scientists. We don’t yet know who will win, but it is likely to be the wrong person, in my view. The money will probably come from Cambridge, England, not Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Rees thinks if the tragedy of Covid has an identified ‘villain’ it would aggravate tense US-China relations

The two scientists involved are Lord (Martin) Rees, the Astronomer Royal and former president of the Royal Society, of Cambridge University, and Steven Pinker, the Harvard linguist, neuroscientist and author of many bestselling books. The subject of the bet, agreed in 2017, is Rees’s prediction that “bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event within a six-month period starting no later than Dec 31 02020.” (The five-figure date format is an affectation of the Long Bets website.) Pinker bet against this.

Both men are good friends of mine. Rees is a pessimist with whom I have often agreeably disagreed; Pinker is an optimist with whom I have often competitively agreed. At the time the bet was made I would have gladly taken up Pinker’s side myself. Biotechnology does more good than harm, I still think. But I now believe Rees has won: Covid is exactly what he predicted.

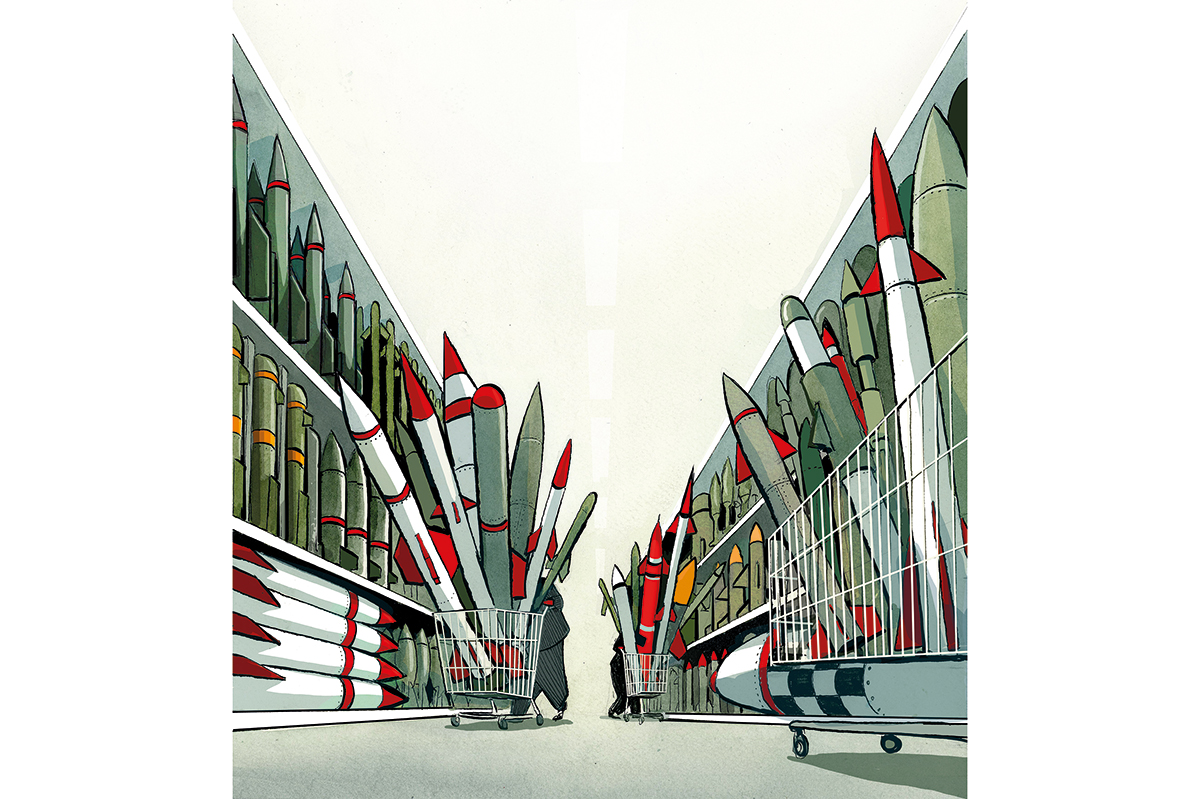

Take a look at Rees’s original justification on the Long Bets website: “Biotechnology is plainly advancing rapidly, and by 2020 there will be thousands — even millions — of people with the capability to cause a catastrophic biological disaster. My concern is not only organized terrorist groups, but individual weirdos with the mindset of the people who now design computer viruses. Even if all nations impose effective regulations on potentially dangerous technologies, the chance of an active enforcement seems to me as small as in the case of the drug laws. By ‘bioerror,’ I mean something which has the same effect as a terror attack, but rises from inadvertence [sic] rather than evil intent.”

That’s a pretty good description of what probably happened in Wuhan. The scientists there were not bioterrorists but even before the pandemic the experiments they were doing were condemned by critics as unacceptably risky. We found out only in 2021 that the year before the outbreak they were party to a plan, with some funding from the United States, to put a genetic sequence called a furin cleavage site into a rare kind of bat virus called a sarbecovirus for the first time and test it on human cells and humanized mice — at an inappropriate biosafety level. In 2019, a sarbecovirus with a furin cleavage site turned up for the first and only time in that very same city, Wuhan, leaving no trace of infected animals other than human beings.

By the end of June 2020, the virus had caused at least half a million confirmed deaths, and by December another 1.4 million, plus many more unconfirmed ones, easily surpassing Rees’s predicted one million “casualties” in a six-month period.

So last time I bumped into Rees I said: “Congrats, you’ve won your bet with Steve.” To my astonishment he replied: “I hope we never do find out what happened in Wuhan.” He thinks if the tragedy of Covid has an identified “villain” it would aggravate already tense US-China relations.

In 2022, the two agreed that they would settle their wager by the end of this year and that Rees would win if by then two public health agencies from a list of eleven had stated that it is more likely than not that Covid began with a lab leak.

So let’s go through the list of eleven agencies. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC): it has taken no position but its former head Robert Redfield thinks a lab leak is almost certain and says his opponents within the government “squashed any debate.” The European, Canadian, Korean, Japanese, Singaporean, Hong Kong and German equivalents: bureaucratic indolence applies and no view has been expressed either way. The Chinese equivalent: fat chance, even though its former head George Gao has publicly ruled out the main alternative, that the virus arrived through a food market. The World Health Organization? You must be joking: it does what China says. How about Public Health England? It has ceased to be.

So none of these agencies is going to make a probabilistic statement about the source of Covid — either way. You might wonder what they are for if not to investigate the worst pandemic in a century. Thus bureaucratic inertia will almost certainly save Pinker $400 and cost Rees £319.

But it will be a pyrrhic victory for the Massachusetts man. In the US, which funded some of the Wuhan experiments, a congressional subcommittee has now concluded that a lab accident “involving dangerous gain-of-function research in China is the most likely origin” of Covid. The man nominated to head the CIA, John Ratcliffe, is already convinced that “a lab leak is the only explanation credibly supported by our intelligence, by science and by common sense.” The nominee to run the Food and Drug Administration, Marty Makary, thinks it’s a “no brainer” that Covid began at that lab. The nominee to head the National Institutes of Health, Jay Bhattacharya, calls the evidence for a lab leak “compelling.”

So it is possible, if they open the books, that soon after he writes the cheque Rees will be vindicated. I asked Rees and Pinker what they thought had really happened. Rees thinks the “odds have tilted in favor of the lab-origin of the virus” and that “US scientists were involved in experiments in the Wuhan lab and therefore had a motive to downplay the possibility that the virus escaped from there.” Pinker says: “I will probably win. This does not mean that my own scientific belief is that Sars spilled over from a nonhuman animal host,” adding: “I confess to remaining uncertain but I’d now go with .6 for the lab leak.”

Matt Ridley’s Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19 is out now.