Had you have taken a direct flight from London to Seoul yesterday afternoon, by the time you would have landed you might have been none the wiser that anything had happened at all. At near midnight South Korean time, President Yoon Suk-yeol imposed martial law across the so-called “land of the morning calm.” Only six hours later it was subsequently, and pointedly, revoked. As South Korean citizens continue with their daily lives, the political establishment has once again entered a period of precarity. Yoon has scored a significant own goal; its implications do not end there.

It is no understatement to say that the decision by President Yoon to impose martial law in an unannounced television broadcast late yesterday evening caught the South Korean people and the world unawares. In effect, striking doctors would be recalled to work within forty-eight hours, and any violators of the decree would have be arrested with immediate effect (an arrest warrant? Forget it.).

Immediately after Yoon’s announcement, the National Assembly building — rotunda and all — became a hub of protest, as police officers and rifled soldiers blocked the entrance. The decree was voted down by members of both the ruling People Power Party and the opposition, namely the leftist Democratic party. President Yoon may have conceded defeat, but his self-defeating actions will have lasting implications on a country that has been no stranger to domestic political scandal.

The very idea of martial law is anything but new for South Korea. After all, the country only became a full-fledged democracy in 1987. Indeed, even in 1948, the very year of South Korea’s establishment as a separate state from North Korea, the government of the first South Korean president, Syngman Rhee, invoked martial law in an attempt to crack down on anti-Communist uprisings. Two years later, as the Korean War commenced, the Rhee government yet again invoked martial law to stifle anti-government sentiment and demonstrations. Rhee — the man who represented the then-unified Korea at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 — would resign in 1960 as opposition grew against him, having imposed martial law one more time.

South Korea’s historical record cannot go unnoticed. After Rhee’s presidency, martial law was frequently invoked by subsequent South Korean presidents, not least Park Chung-hee, who ruled South Korea from 1962 until he was assassinated in 1979, notoriously by one of his own spy chiefs. For all of Park’s successes in rapidly bolstering the South Korean economy, we must remember that he himself took power by means of a coup d’état in 1961, deposing the then-president, Yun Bo-seon.

Park would periodically impose martial law to crack down on dissent. After his sudden assassination, martial law was once again be enforced under the regime of his successor, the military general, Chun Doo-hwan, leading to the suppression of pro-democracy movements and culminating in the Gwangju Massacre, which killed hundreds of student demonstrators in the southern city of Gwangju, in May 1980. Since South Korea’s transition to democracy, however, martial law had not been invoked — until yesterday evening.

We must remember, too, that it is only in very recent memory, in 2017, that South Korea witnessed the last impeachment of a president: Park Geun-hye, the daughter of Park Chung-hee. Ms. Park’s presidency was replete with scandal: she was convicted of bribery, leaking government secrets – most notably to close confidante and businesswoman, Choi Soon-sil — as well as abuse of power. She has always denied the charges. Seven years later, Yoon’s position as president is becoming increasingly untenable; the likelihood that he fulfills the two remaining years of his presidency are becoming slimmer by the minute.

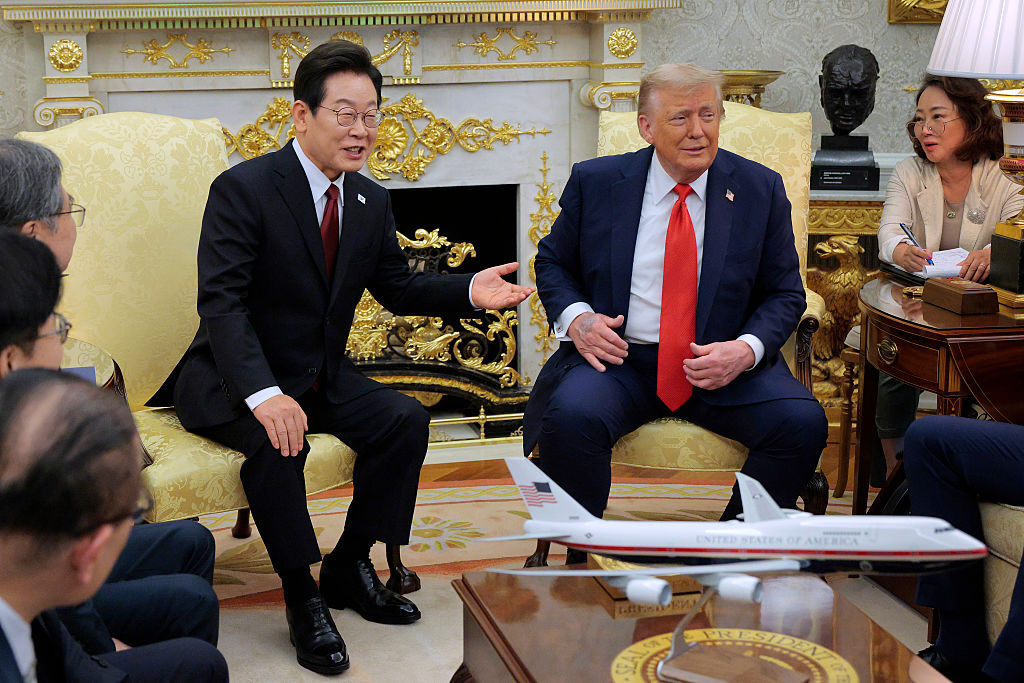

One by one, President Yoon’s senior ministers — most recently his defense minister — have been tendering their resignations. Even before yesterday’s events, the South Korean ruling party had been mired in inter-party and intra-party tensions. It is perhaps no surprise that the opposition party, the leftist Democratic party — led by Lee Jae-myung, Yoon’s rival in the 2022 presidential election — has called for the lame-duck president to be charged with treason and face impeachment.

Were the leftists to take over, however, Yoon’s successful South Korean foreign policy would all amount to nothing. The Democratic Party will be anything but a successful alternative, as they will likely undo the ruling party’s hawkish stance on North Korea, its rapprochement with Japan and attempt to tone down the incumbent People Power party’s comparably harsh stance on China.

Amidst all of this tumult, there may be one small reason to be vaguely optimistic. Yesterday’s revocation of martial law, following the National Assembly vote, highlights how democracy in South Korea is, at least for now, functioning and flourishing. Perhaps this is something to be grateful for.

Leave a Reply