Bees and mammoth bones, a shipwreck, horse urine (preferably female), a seventeenth-century craftsman and a twentieth-century genocide. Playing an extended narrative game of Only Connect in her latest book, the musicologist Kate Kennedy takes a bird’s-eye view of four lives and five centuries as she turns her own instrument, the cello, into a prism. Part history, biography and auto-biography, with digressions into anthropology, acoustics and aesthetics and an intriguing cast of characters, Cello sings richly. But you have to be willing to lgo on the journey.

Has publishing reached peak personality-stakes? Whether the subject is swimming or stamp-collecting, non-fiction seems wearyingly determined to rebrand itself as memoir, our author, also our hero, overcoming adversity and scaling new heights of self-knowledge. Here lwe meet the teenage Kennedy clutching a prized scholarship to Wells Cathedral School, her ambitions for a career as a cellist cut cruelly short by tendonitis. Hospitalized in her ensuing despair, she decides to live, “even if that meant a future without my cello.”

Kennedy’s complicated relationship with an instrument she still in fact plays to a professional standard becomes the springboard for a journey to “uncover the stories of cellists and their instruments,” and understand her own feelings for her “first love.” As a precis, it’s a serious undersell, a structural crutch for a project whose unfamiliar stories soar without need of support. The stakes of the four lives at the center of this group biography are high enough — often tragically so — without this extra turn of the screw, and the questions Kennedy extrapolates from them deliciously esoteric.

Nevertheless, off she and her beloved cello sidekick gamely go, on a trip that takes them from an Oxford instrument workshop to Paris, Berlin, Cremona and even Lithuania on the brink of recent Russian hostilities, traveling and playing in the sonic footsteps of four singular musicians.

The principal cast enter gradually. In Berlin we meet “the Hungarian Casals” Pal Hermann (1902-44), whose extraordinary precocity took him to the brink of celebrity before anti-Jewish laws robbed him of the right to perform publicly. Captured and sent to Drancy concentration camp in 1944, his “vulnerable” sound and “vivacious” delivery dissolved into terrible silence at the end of a journey by cattle truck to Lithuania’s Ninth Fort — the Fort of Death. His Gagliano cello, rescued at serious risk by family members, was luckier.

How many people can claim that their cello-playing literally saved their life?

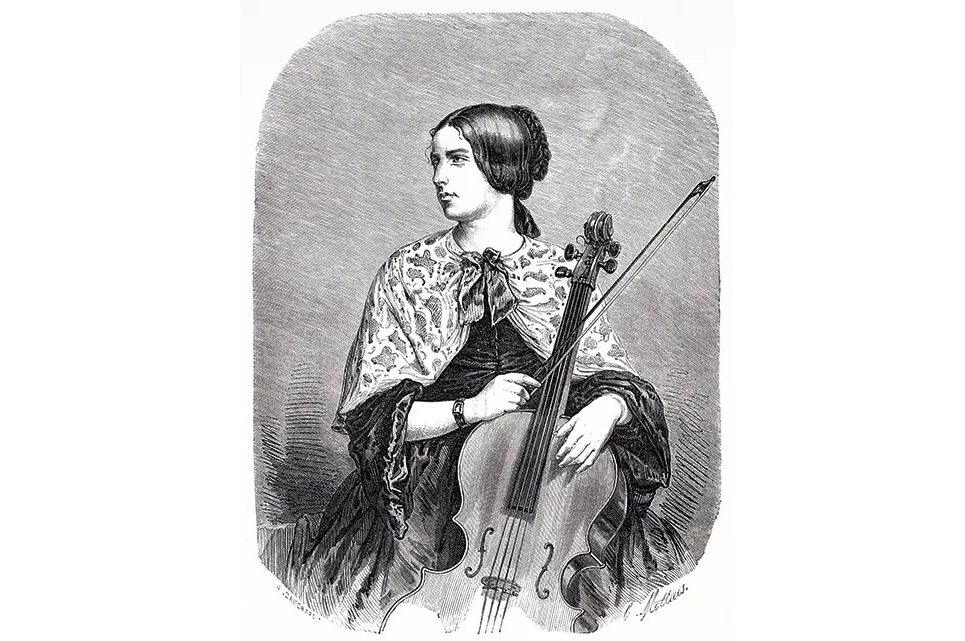

In Paris, Kennedy picks up the trail of Lise Cristiani (1827-53), “as much a spectacle as a cellist,” whose international tours introduced “the very idea of the female cellist” to a startled and not a little titillated public, turning it from “a novelty into a blueprint for the future.” Her delicate sound and virginal, graceful image (modeled after no less than St. Cecilia by male relatives with a keenly cynical grasp of branding) belied her extraordinary daring. This took her and her cello, contained in a wolfskin pelt and iron box, to “the end of the world” — Siberia, Kazakhstan and the Caucasus, where she died of cholera, aged just twenty-six. Her cello — a Stradivarius that still bears her name and the scars of its extreme travels — survives, safe but largely silent in a glass case in Cremona’s museum.

If the most inscrutable figure is Amedeo Baldovino (1916-98), the cellist of the Trieste Piano Trio, whose career and precious “Mara” Stradivarius both somehow survived war, invasion and a serious shipwreck, then the most vividly painted is the now ninety-nine-year-old Anita Lasker-Wallfisch. How many can claim, as she can, that their cello-playing literally saved their life? Plucked from certain death at Auschwitz, she assumed the vacant position of cellist in the camp’s orchestra — a “human jukebox” for SS guards — where she played solo for Josef Mengele, surviving both Auschwitz itself and later Bergen-Belsen.

The human leads are compelling and carefully drawn out by Kennedy’s new research. But their instruments are almost more so. Kennedy reminds us that in blind test after blind test no one has reliably distinguished a Stradivarius (those sixty-three surviving instruments played by the likes of Jacqueline du Pré and Yo-Yo Ma that make up the greatest of their kind, a “wooden family of celebrity sibling”) from a contemporary cello. But she also embraces the unquantifiable fact that this is far from the whole story, teasing out the distinct identities of instruments that shape their players as much as the other way round.

Are Strads really the best, and, if so, why? After interviewing luthiers and players lucky enough to have risked the “unpredictable wrestling” with these notoriously challenging instruments which must be coaxed and won over gradually like living things, Kennedy offers some practical information (concerning the type of wood, the exact recipe for varnish, glue — possibly mixed with mammoth bones for inlay — and bow hairs from mares tempered by their own urine) as well as more numinous conjectures. She also draws back the curtain on the unthinkable. What happens when a Stradivarius is broken, or virtually destroyed — as in the case of Baldovino’s “Mara,” lost in a shipwreck on the River Plate, subsequently discovered in fragments and painstakingly rebuilt? And, above all, what do we do with those instruments that do survive intact? Do we preserve them silent in museums or risk letting them sing themselves to death in the wild?

A cello, Kennedy acknowledges, “is not a medium and playing it is not a séance.” But in conversation with other cellists she tests her own conviction that “we can look for someone in their instrument,” teasing out the spirit of objects that take some 300 hours to make and thousands more to master as a soloist — instruments with “their own musical opinions,” but which assume the imprint of previous players “like a finger in wax.” Kennedy explores the cello’s singularity: its physical resemblance (articulated so wittily by Man Ray’s “Le Violin d’Ingres”) to the human form and its role as “body double” for a player; its androgynous combination of a woman’s curves and a man’s singing range; the shifting identities it takes in relation to its players — child, lover, alter ego, best friend.

Interludes allow Kennedy to bring in other voices. We hear from makers and dealers, including the avant-garde performer Anton Lukoszevievze, who invents new sounds for the cello (and was once asked to play the instrument with a meat cleaver as a bow) and the physicist Martin Bencsik, whose garden in West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire, houses a cello-turned-hive. This is home to a colony of honey bees whose vibrations and structural improvements to their home create “a secret duet” of strange beauty between man and nature.

There are also contributions from Steven Isserlis, Christian Poltera (who currently plays the “Mara”) and the Berlin Philharmonic’s principal cellist Ludwig Quandt, who battles extraordinary physical challenges to continue playing. And there is a moving conversation with Julian Lloyd-Webber who sold his own “Barjansky” Stradivarius after a herniated disc forcibly and suddenly ended his career in 2014. “There is nothing sadder,” he says, “than a cello that is not played.”

That silence and more — players muted by violence, gender, chance or illness; instruments muffled by destruction or loss — supplies a space for Kennedy’s generous, fascinating book: as much a history of absent or imagined sounds as real ones.