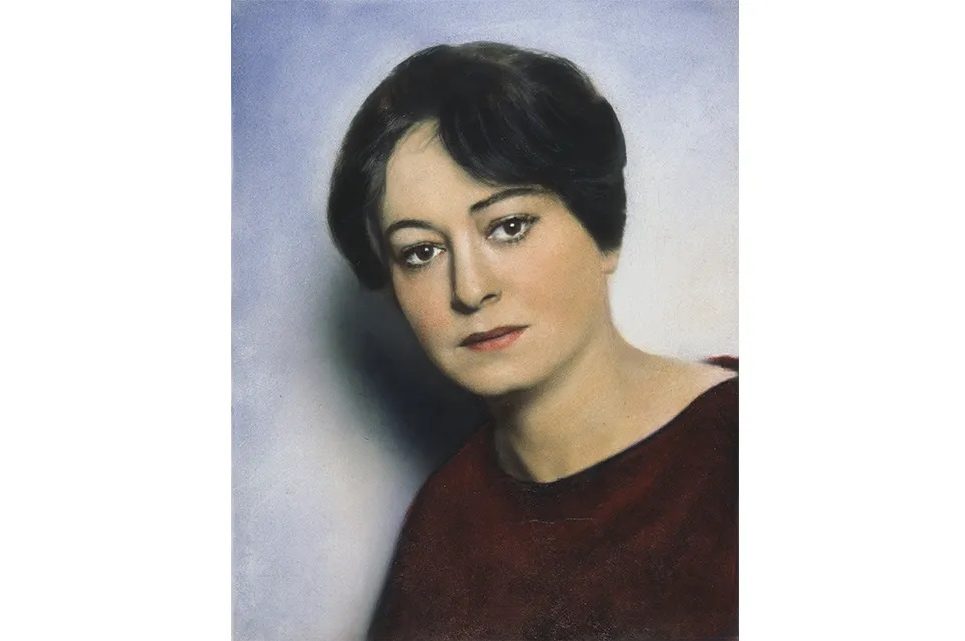

Hollywood didn’t kill Dorothy Parker, but booze probably did. In fact, if Hollywood hadn’t paid her so well to spend so much time at home, she couldn’t have afforded the booze — as well as maintain a lifelong ability to insult almost everyone she loved while still earning their (sometimes reluctant) affection.

It’s hard to believe that Parker didn’t take her film work seriously, since she kept producing such good work

Gail Crowther’s Dorothy Parker in Hollywood, her latest book (she has written entertainingly on other notably cocktail-absorbed writers such as Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton) is a focused, fun and almost recreationally enjoyable brief biography not of a writer but of a well-framed aspect of a writer’s life — in this case, Parker’s critically neglected years as a well-paid and genuinely gifted screenwriter.

Born in 1893, near Long Beach, New Jersey, to middle-class Jewish parents, Parker suffered the loss of her mother when she was only five; and when her father later married a Jesus-obsessed Catholic, it taught Parker a rule she seemed to follow for the rest of her life: if you love someone too hard, don’t do it too openly or life might take what you love away.

So while she seemed to feel deeply for others, she was careful to act as though she didn’t. Meanwhile, she wrote some of the lightest, funniest, most cynical verse in American literature. Her first sales, to the popular magazine Vanity Fair in 1916, with titles such as “Women: A Hate Song” and “Why I Haven’t Married,” managed to carve up both the males and the females of her species as if they were fish. One can only imagine that if Parker had lived long enough she would have similarly eviscerated just about any of our age’s multifarious sexual identities with the same caustic wit.

Hired as Vanity Fair’s fact-checker and writer of advertising captions, she moved to Manhattan at the first opportunity, lived in rooming houses, befriended the likes of Thorne Smith and Robert Benchley, and took a temporary job in editorial when her bosses went on vacation. During this time she helped invent the often endless lunchtime indulgence later immortalized as the Algonquin Club, a daily “round table” of notable wits and raconteurs which included the likes of Harpo Marx, S.J. Perelman and Charles MacArthur. Then, when Vanity Fair sensibly fired her for forsaking her proper duties, she went freelance and never looked back. Later, she dismissed this brief period of unprofessional lunchtime dawdling as “just a bunch of loudmouths showing off.”

Her first marriage, to a stockbroker, ended unhappily (in fact, he was the first of two husbands she drove to enlist in the military); it seems to have inspired both her alcoholism and a predilection for failed suicides. After a difficult and illegal abortion, which she referred to as “putting all her eggs into one bastard,” she tried drinking shoe polish, slicing her wrists and mixing barbiturates with alcohol. Eventually, she went west in the tail wind of perhaps her greatest friend and influencer, Benchley, earning $300 per week as a screenwriter, often simply to sit around waiting for instructions from her producers. She continued making long (and even better paid) trips to Hollywood for the rest of her life.

Her screenwriting years are most notably recalled for her descriptions of Hollywood as not simply the latest “freshest” hell, but the sunniest. (She often asked, in reply to the ringing of phones and doorbells: “What fresh hell is this?”) She referred to the prevalence of shedding palm trees as looking like they had “died on their feet.” And her characteristic assessments of the people she worked for often included inventive cursing, such as her description of MGM as “Metro-Goldwyn-Merde.”

But, as Crowther convincingly argues, it’s hard to believe that Parker didn’t take her film work seriously, since she kept producing such good work. She was nominated for two Academy Awards — including for the many-times-remade A Star is Born (originally featuring Fredric March and Janet Gaynor); and, unlike with her friend F. Scott Fitzgerald, her smart and often well-reviewed dialogue kept making it into the final cuts of star vehicles for the likes of Henry Fonda and Bette Davis, as well as one of Alfred Hitchcock’s formative thrillers, Saboteur.

She wrote possibly the first original script about female alcoholism, Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman, starring Susan Hayward, and while her own alcoholism resulted in a second divorce, she might well have continued prospering in Hollywood if it hadn’t been for her politics.

Regularly active on behalf of left-wing causes, such as defense funds for the Scottsboro Boys (the nine African-American teenagers accused of raping two white women in 1931) and support for the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, she was inspired by her friend Ernest Hemingway to visit Spain during the civil war and write journalism in support of the anti-Franco forces. As a result, she was monitored by the FBI during World War Two and while testifying before the HUAC several years later, she made the perfectly sensible claim: “Listen, I can’t even get my dog to stay down. Do I look to you like someone who could overthrow the government?” She was blacklisted anyway, and her screenwriting career never recovered.

Despite her undimmed reputation as one of America’s greatest writers of short stories and darkish-light verse, Parker outlived her notoriety, and her final years in Hollywood were remarkably dismal. After remarrying her second husband, she lost him to a plastic laundry bag that he tied around his neck after a night of his normally despondent drinking, and Crowther summarizes her final days thus:

Drinking to excess, living among piles of dog waste, smoking, falling asleep, waking up to start drinking all over again. On the one hand, she just simply seemed to disappear. On the other, her legacy began to cement itself as though she were already dead.

But that was the life Parker wrote about so memorably in “Coda:”

This living, this living, this living

Was never a project of mine.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.