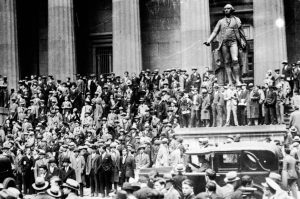

When Domingo Cavallo implemented at the start of December 2001 a restriction on cash withdrawals, he unwittingly unleashed a month of rioting and looting across Argentina that would leave thirty-nine people dead. Police brutally cracked down on protests that quickly spread as the country’s economy fell to pieces.

The basket of laws enforced by the then-finance minister became known as the Corralito and were a desperate response to a devastating — and worsening — economic crisis. A series of setbacks had caused both individual Argentines and companies to convert their pesos into dollars and get them out of the banks. Some 25 percent of the country’s cash had been spirited away since the beginning of the calendar year.

The corralito put a stop to this. But it also did something far more drastic. It turned Argentina against the banks.

There has long been a core of Argentines who say they will never trust a bank with their savings. The most common form of saving is to stuff your mattress with US dollars. Some estimates suggest that Argentina possesses more dollar bills per person than any other country — including the United States. “I would rather be robbed by a thief than a bank,” was one savers’ assessment during the 2020 recession. Indeed, stories abound in western Argentina of Chilean gangs hopping across the border to raid homes in pursuit of hidden greenbacks.

Such attitudes come from a deep distrust of the peso. To live in Argentina has been to endure decades of boom and bust economic cycles, characterized by extremely high inflation eroding the value of the national currency. Government interventions like the corralito have not helped.

Javier Milei swept to his unexpected election victory last year amid triple-digit inflation with a promise to smash up the economic orthodoxy. He has since enacted a brutal regime of austerity to balance the books. Inflation has been, partially, tamed. Year-on-year prices are still more than doubling, but even this represents a cooling from its high of nearly 300 percent. The trajectory is downwards.

One of his flagship policies during the campaign was dollarization. Throw out the ailing peso with the bathwater and adopt US dollars as the country’s official currency. A problem raised by multiple economists at the time was simple. How could Milei do this when Argentina simply doesn’t have any dollars?

Milei’s advocates made an equally simple point. Argentina has plenty of foreign currency. The only problem: they are stuffed into mattresses across the country and not, as would be required, in the banks. Getting naturally distrustful savers to deposit their hard-earned dollars seemed an impossible task. But has Milei achieved the impossible? Well, sort of.

Manuel Adorni, Milei’s spokesman announced this week that $18 billion has flooded into Argentine banks from mattresses, safe deposit boxes and overseas accounts. A tax amnesty introduced by the administration had been a “success,” he said, and the extra dollars would open up new credit opportunities to Argentine banks. This is a sign of trust in Milei and his efforts to get the economy under control. In a further boost, Reuters reported that deposits in Argentine dollar-denominated accounts had also increased since June. The first round of the amnesty closed on Thursday. Deposits of up to $100,000 were free of tax, with those above that threshold levied at 5 percent. This will increase to 10 percent in January and then to 15 percent in April. So officials will hope that the dollar rush isn’t over yet.

Milei supporters, though, shouldn’t get too excited just yet. While a positive development, the $18 billion remains a fraction of the estimated $277 billion that sits outside the formal banking system. There is still clearly a degree of caution and, with the most generous stage of the amnesty over, reserves are unlikely to accelerate greatly without further economic changes.

Financial analysts are retaining a note of caution. A note from JPMorgan last week said that the positive impact of the windfall would still depend on an increase in credit to the private sector.

Meanwhile, poverty has soared in Argentina under Milei’s presidency. Some 55 percent of the population are now living in poverty according to figures from one of the country’s leading universities. As many as 70 percent of the population earns less than $550 a month. These data points could be seen as a shadowy portent of things to come. But President Milei has managed to keep things under control by reining in inflation — for now.

A 2001-style disaster looks unlikely to rear its head over the coming months. But weary Argentines know that nothing is certain when it comes to economics. And when it comes to the prospects for the country, much might depend on how many more mattresses are emptied over the next few months.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply