Vertrauen ist gut, Kontrolle ist besser — trust is good, control is better — is a popular German saying. It’s also the state’s motto for overseeing Europe’s biggest economy, which is now being run into the ground. Germany’s economy is officially expected to shrink in 2024 for the second year in a row. Berlin’s Social Democratic chancellor Olaf Scholz and his Greens vice-chancellor Robert Habeck, who are fighting for their political lives as their coalition crumbles around them, are to blame.

Only one German sector is growing: the state. Government consumption grew by 2.8 percent from mid-2023 to mid-2024. Dealing with bureaucracy costs German business €67 billion ($73 billion) per year, says Berlin’s Federal Justice Ministry.

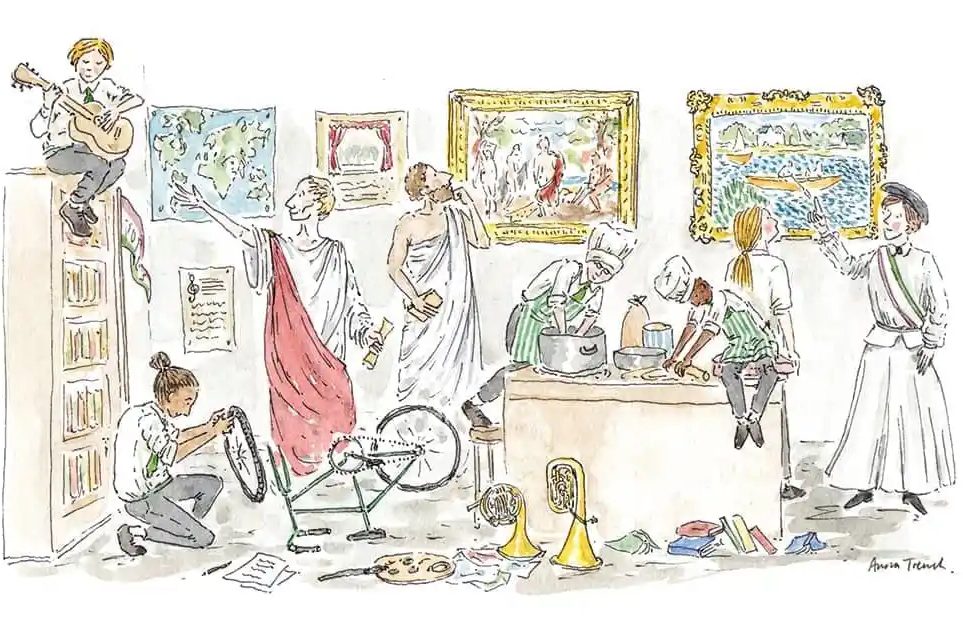

Germany is a country in which it is not always easy to do business

Scholz’s answer? Expand the state, more debt, redistribute more money and, his party’s all-time greatest hit: tax the rich. Germany already has the second highest taxes in the OECD club of industrial nations. The plan could raise the top income tax rate to as high as 56 percent from the current 45 percent, German media reports. The SPD calls this a tax on the top one percent, yet it’s not just aimed at millionaires — it kicks in for those earning over €280,000 ($300,000). Final details will be unveiled for the SPD’s re-election campaign next year.

Scholz’s latest antics are to condemn a possible takeover of Germany’s stumbling Commerzbank by Italy’s far more successful UniCredit bank as “unfriendly attacks.” Petty nationalism trumps creating European banking champions.

While Germany remains Europe’s largest economy, the truth is that this is a country in which it is not always easy to do business. In the twenty-five years I’ve been running our family forestry business in eastern Germany, the biggest problems haven’t been markets or weather, but rather the grasping hand of the German state. These troubles are structural and go back to German reunification in 1990.

I bought our first forest from the state during privatization of ex-communist East German land. Big mistake. The contract said I needed to have my main residence “close by” the forest. Nowhere was it defined what this meant in miles. I ended up being dragged to court by the BVVG privatization agency, which belongs to the German Finance Ministry, over claims that my home was too far away. The legal circus lasted five years and cost me tens of thousands of euros before I eventually won.

This year, we again went to battle with the German state — and lost. Adjoining a forest we own in Saxony-Anhalt state are twenty-eight hectares of meadow. Our son is more interested in beef cattle than in trees, so the plan was to buy the meadows and start raising grass-fed beef. After years of negotiating, we signed a contract to purchase the land from a neighbor. “Not so fast!” the state said. When it comes to farmland, Germany is a command, state-planned economy. With no plausible explanation, the county government not only blocked the sale to us but awarded the land to another farmer. This wasn’t some poor, struggling smallholder but rather one of the big landowners in the region.

Such stupidities pale compared to the Scholz-Habeck bungling of what they claim is their top priority: building wind turbines and solar parks to speed Germany to net-zero nirvana. But they are revealing of the trouble of doing business in Europe’s supposed economic powerhouse.

The Scholz-Habeck government was lightning fast when it came to shutting down Germany’s last nuclear power stations. So fast that Habeck may have ignored expert voices warning against it. This is now the subject of a parliamentary investigation in the Bundestag.

The big problem is that Germany is proving unable to speed up the construction of new wind parks and the high-tension lines needed to shift electricity around the country. In the first half of 2024, just 250 new windmills were built in Germany. That’s only a fraction of the year’s target.

I’ve been trying to build a wind park with my neighbors in a forest in eastern Germany since January 2021. It’s been approved by the town council and a year-long environmental assessment found scant evidence of conservation conflicts. I have signed contracts surrendering land to be reforested as compensation for the footprint of the windmills. You would think all is good. But you would be wrong.

Berlin will soon pay a heavy price for this sluggishness on planning for the future

Germany’s Energiewende, or energy transformation, is running head-on into a wall of state bureaucracy, even in sparsely populated eastern Germany. As the Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper warns: “The success of the energy transition in Germany will be decided in the east.” But the German state doesn’t seem to have woken up to the fact.

Earlier this year, I was told that the wind park was too big and ordered to reduce it from fifteen to five windmills. Other state agencies soon weighed in. A conservation official indicated he is against windmills in forests — even though they are legal in Brandenburg state — and would oppose the wind park. Then the historic monument agency claimed the wind park might detract from sightlines at two, historically trifling castles.

Laws that Scholz and Habeck have passed, which they claim will speed up renewables, don’t seem to concern the officials tasked with giving the go ahead to wind farm projects. But Germany will soon pay a heavy price for this sluggishness on planning for the future.

Where the country gets its energy from in the years, and decades, to come will become a huge problem for the world’s third biggest industrial economy. Coal-powered plants are being rapidly closed. The lignite electricity plant near my woods — that’s been running 24/7 all year — will be shuttered in 2028.

Habeck’s suggestion on dealing with energy misery — if you can believe it — is to ration electricity. German industry should produce only at peak electricity periods and electric cars and heat pumps, that he insists home owners install, may have their power cut off.

A poisoned cocktail of massive over-regulation, high energy costs and a lack of skilled workers has again made Germany the sick man of Europe

“This is a great idea for, say, bakers who bake bread at night. Shall they wait until the morning when the sun rises?” asks Jörg Dittrich, head of the German Confederation of Skilled Crafts (ZDH).

A poisoned cocktail of massive over-regulation, high energy costs and possible future energy shortages, lack of skilled workers and generous social welfare for those who don’t — or won’t — work has again made Germany the sick man of Europe.

Deindustrialization is real. German companies are closing factories at home and fleeing the misery. Volkswagen plans to close at least three of its ten plants in Germany and will downsize the rest, according to the company’s works council. There will be wage cuts and some divisions will be moved abroad, says the works council. VW and Mercedes-Benz are investing billions of dollars in the US. Chemicals giant BASF is doing the same, flanked by a “permanent” downsizing of its Ludwigshafen headquarters, along with thousands of job cuts in Germany.

These aren’t isolated examples: around 37 percent of German companies are considering cutting production or moving abroad, says a survey by the DIHK Chambers of Industry and Commerce.

Meanwhile, US chipmaker Intel in September announced a two-year delay for a planned €30 billion ($33 billion) chip plant in eastern Germany. This is despite the fact that Scholz’s government had pledged €9.9 billion ($11 billion) in subsidies.

Scholz is marching Germany into decline

Despair over Germany as a place to do business also led me to start bailing out. I bought a forest in the US southeast state of Georgia in 2017. Georgia is a center of American forestry. It has light-touch regulation. When I deal with Georgia bureaucrats, it’s still a shock to discover that most want to help me succeed. Selling up in Germany and shifting to the US makes business sense. In Georgia, we do what tree farmers increasing cannot do in Germany: we simply produce what the market wants.

But creating guardrails and getting out of the way so an industry can produce for the market is foreign to Scholz and Habeck. They’re too busy regulating, banning, subsidizing, magically thinking about electricity as they close nuclear and coal plants, and fantasizing about post-industrial net-zero.

Any responsible head of government would look at Germany’s misery and say “this cannot go on.” He’d sack at least half his cabinet and place every sacred policy cow on the table and slaughter those that aren’t delivering. But there’s no sign Scholz will do this.

Chancellor Scholz is responsible for Germany’s failure to rebuild the military. He’s responsible for Berlin’s failure to play a leadership role in Europe. And now he’s to blame for the tanking economy. The gentleman’s not for turning, even as he marches Germany into decline, debacle and irrelevance.

Avanti dilettanti!

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.