When Kim Jong-un does not get what he wants, he makes his displeasure known far and wide. Over the past few weeks, one would have thought that Kim would be reasonably content. In return for sending artillery shells, ballistic missiles, and most recently, troops to Russia, North Korea has been receiving food, cash, and most likely, technological assistance, the latter which is what Kim craves the most. But instead of calming down, Kim has responded in the way that he knows best — by launching yet another intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) designed to hit the US mainland.

From North Korea’s perspective, Thursday’s launch of a Hwasong-18 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) was something to be proud of. It was not just the fact that, as Kim Jong-un proclaimed in a statement soon afterwards, the ICBM test signaled North Korea’s unwavering “will to respond to our enemies.” The timing of the launch was no accident, with the world’s eyes glued to the Ukraine war and as observers keen to dissect just who has been — and will be — sent from Pyongyang to Kursk and beyond.

For North Korean troops, many of whom will be little more than Putin’s mercenaries, the war will provide crucial combat experience in a modern-day war, but on an unfamiliar terrain with unfamiliar people and in an unfamiliar language. Their deployment has catalyzed a deluge of speculation as to how they will fare, and what tactics they will use. Thus, for the North Korean regime, how better to divert global attention from one sanctions-violating action to another than by testing an intercontinental ballistic missile for the first time in nearly a year?

This morning’s launch was not just any ordinary ICBM test-fire. The missile may have only flown for ten minutes longer than the ICBM launched in December 2023, but with a flight time of 86 minutes — and having reached a height of 4,350 miles — it marked the longest flight time of any North Korean missile to date. Moreover, the fact that this test was of a solid-fuel ICBM underscores another concerning development in North Korea’s missile technology. Solid-fuel missiles are not only easier to maneuver than their liquid-fuel counterparts, but harder to detect.

The bleak reality is that with its missiles flying higher, further, and for longer than before, Pyongyang is making progress on its quest to improve the scope and sophistication of its nuclear weapons and delivery systems. This was, perhaps, to be expected. After all, in January 2021, Kim Jong-un announced his five-year military plan with the explicit aim of enhancing the quantity and quality of his conventional and unconventional weapons arsenals, including satellite technology, drones, ICBMs with a 9,320 mile-range, and, of course, solid-fuel missile capability.

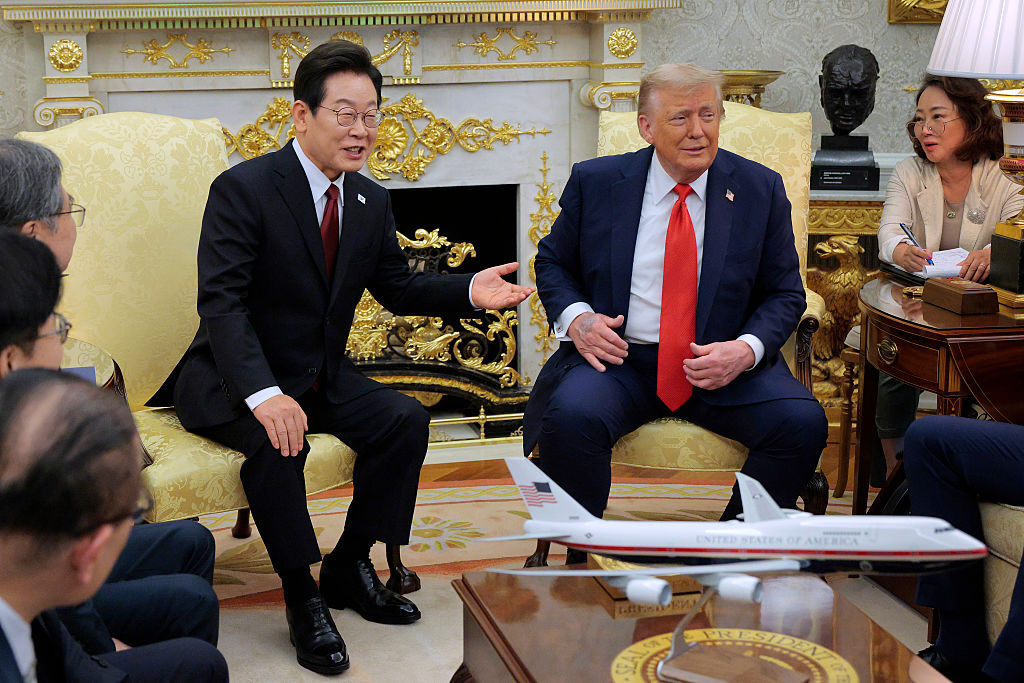

But the North Korean leader is upset. For a start, he is unhappy — as he has always been — with South Korea’s alliance with the United States, a relationship that is only going to strengthen over time. With North Korea justifying today’s ICBM launch as a response to the “nuclear alliance” between Washington and Seoul, Kim is making clear how he wants to be left alone and has no interest in negotiations unless North Korea will benefit. In Kim’s mind, the United States’s strengthening relationship with South Korea and Japan will not stop him from spending vast sums of money on missile delivery systems at the expense of the 26 million North Korean people. In fact, it will only motivate him to become even more aggressive.

Relations between the two Koreas have plummeted to a nadir over the past year, and North Korea is largely to blame. By declaring, at the start of the year, that South Korea would become the North’s “primary foe” — rather than part of the same, divided but once unified Korean nation — Pyongyang has sought to justify heightened provocations towards its southern counterpart. The most infamous such provocation has been the ongoing sending of excrement-filled balloons across the inter-Korean border, with one such disbursement, only last week, reaching the South Korean presidential compound.

But maybe Kim can smile a little. Earlier today, in what was a not-so-tacit admission of just how tense inter-Korean relations have become, authorities in the South Korean Gyeong-gi provincial government declared three cities and counties near the inter-Korean border to comprise a “danger zone.” No anti-North Korean leaflets — what North Korea claims is the cause of its retaliation by balloon — could be dispatched from these regions, despite South Korea’s constitutional court repealing a ban on the sending of such leaflets in September 2023.

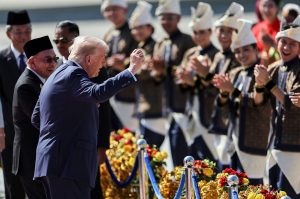

With only one week to go before the US presidential election, Kim Jong-un will not be calming down. North Korea frequently ramps up provocations in US election years, both prior to the election and in its immediate aftermath. Even though a Trump victory will likely lead to Kim Jong-un meeting his correspondant for yet another round of optical summitry, sometime in the future, such occasions will likely have little effect in altering North Korea’s attitude towards the West.

When after the infamous “no deal” of the Hanoi Summit in February 2019 — when Trump and Kim did not even have lunch — North Korea’s now-Foreign Minister, Choe Son Hui, declared that the Supreme Leader had “lost the will to negotiate,” perhaps she was foreshadowing just what the next five years would hold. “I want; doesn’t get,” so the saying goes: but if you’re Kim Jong-un, you’ll just keep testing missiles.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply