In Christian countries, it’s typical to put things off until “after Christmas” when the new year begins. In Israel, the equivalent is “after the festivals.” The Jewish fall festivals begin with Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year followed by Yom Kippur and the eight-day festival of Tabernacles, Sukkot.

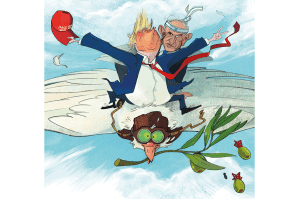

Throughout his career, Netanyahu’s talent has been finding people he can blame for restraining him

This year, Israelis cowered in their bomb shelters on October 1, the day before Rosh Hashanah, when 180 Iranian ballistic missiles rained down on the country. The long-threatened strike, supposedly in retaliation for the killing of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran and Hezbollah head Hassan Nasrallah in Beirut, was mostly foiled by Israel’s Arrow missile defense shield, with the help of the US, UK and France intercepting missiles. But dozens of missiles found their targets, damaging Israeli air bases and a school.

An Israeli military response was inevitable. After a similar attack in April, Israel restricted its response to a symbolic hit on Iranian air defenses, destroying a costly S-300 system but causing no broader damage. This time, it was going to be different.

The two big questions were “what” and “when.” Many in Israel expected the counter-attack to wait until after the festival period. And so it was. This weekend, Israeli jets bombed targets inside Iran.

More important, though, was the debate over what to hit. Initial speculation was that Israel might target Iranian oil production, which would really hurt the regime’s main source of income. But Iran in turn threatened to hit oil targets in neighboring Arab states, potentially triggering a global crisis by spiking fuel costs ahead of winter. The Biden administration and basically the whole western world urged against this step.

Another much-discussed option was striking Iran’s nuclear program. For decades, Iran’s civilian and military nuclear advancement have been close to the top of Israel’s threat list. Benjamin Netanyahu, even before his return to power in 2009, was a major advocate for crippling sanctions and military action to prevent Iran from obtaining nukes. Finally, this could be Israel’s chance to set back Iran’s nuclear ambitions for many years.

This option was promoted by the messianic far right in Israel, which truly believes that a civilizational war may usher in the End of Days and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem. But it was also the preferred option of many moderate right-leaning types who believe that war between the Iranian regime and Israel is inevitable, and that waiting another twenty years until that regime has nuclear missiles is foolish and shortsighted; better to take action now.

The western powers opposed this option too. While perhaps justified, it would be escalatory, upping the ante in a way that would oblige Iran to respond and potentially lead to an ongoing war.

So that left the option of military targets, of which there is no shortage in Iran. And it’s this option that Israel ultimately took this weekend, hitting sites across the country. Iran remained tight-lipped about the targets, claiming four members of the military were killed, but residents of Tehran saw and heard explosions in the outskirts of the city.

By Sunday morning, satellite photos showed destroyed buildings in military bases near Tehran and in Parchin, and Israeli sources began to brief what they’d hit: planetary mixers. These high-precision machines are the mutant cousins of the kitchen stand mixer, they’re used for making the solid fuel used in ballistic missiles. According to the Israeli journalist Barak Ravid, Israel targeted every single rocket fuel mixer in Iran, and perhaps even a couple in Syria for good measure. Destroying them would essentially end Iranian missile production for months or years.

That’s bad news for Iran and good news for Israel. But it’s also tough luck for the Houthis in Yemen, who rely on arms from Iran, and for Russia, which had been seeking to buy Iranian ballistic missiles for use against Ukraine.

A couple of supposedly “advanced” S-300 air defense systems were also destroyed, not that they seem to have done Iran much good in the first place; no Israeli jets were downed in the attack.

Iran today seems in a bit of a quandary. There is no immediate threat of retaliation from the regime, just bellicose but vague language. Meanwhile, parts of the Israeli right criticized the strikes as not harsh enough, mostly blaming Joe Biden for restraining Netanyahu’s hand.

Netanyahu, though, has been prime minister for most of the last fifteen years. If he truly wanted to bomb Iranian nuclear sites with warplanes, he would have done it by now. Throughout his career, Netanyahu’s talent has been finding people who he can blame for restraining him: left-wing coalition partners, Israeli judges and US presidents.

For most of the last year, neither Israel nor Hezbollah wanted a broader war in Lebanon. When that changed, and Israeli leaders decided it was time to take on Hezbollah, it wasn’t subtle; two weeks of pager bombs, walkie talkie bombs and dramatic assassinations.

As it stands, Israel and Iran don’t want an open war — yet. Both sides are still looking for reasons to de-escalate. But Israel’s strikes have proven that if war comes, there is very little that the regime can do to prevent the Israeli air force from hitting what it wants, when it wants.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply