On the November 15 Xi Jinping will mark the twelfth anniversary of his becoming general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party — the sixth paramount leader in China since Mao Zedong established communist rule in 1949. One of the consistent features of Xi’s rule has been China’s hostility to India. People’s Liberation Army incursions across Indian borders became a given. So, the announcement yesterday that India and China have reached a Himalayan border agreement comes as something of a surprise. Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar announced:

We reached an agreement on patrolling [the border], and with that, we have gone back to where the situation was in 2020, and we can say… the disengagement process with China has been completed.

From the beginning, communist China’s relations with India, which had gained independence two years earlier in 1947, were fraught. Albeit socialist brothers-in-arms, Mao resented prime minister Nehru for taking four years to acknowledge China’s annexation of Tibet. Salt was rubbed into the wound when India agreed to host the exiled Dalai Lama.

Agreeing to a standstill in the Himalayas is no big deal

A brief period of harmony followed. It was skin deep. Nehru grandly boasted that he had escorted the Chinese prime minister, Zhou Enlai, to the Third World “lovefest” of non-aligned nations at the Bandung Convention in West Java in 1955. When Enlai heard this claim, he was reportedly surprised at the “effrontery of a third-rate power like India claiming to introduce to the world the prime minister of a first-rate power like China.” It was a macho face-off between two new governments which, by dint of their huge populations, saw themselves as emerging global powers.

Within three years India and China were at loggerheads over their Himalayan border which had been demarcated by British Indian foreign office minister Henry McMahon in agreement with Tibet at the Simla Convention in 1914. Having renounced this agreement, communist China began construction of a road through the disputed Aksai Chin, a Himalayan plateau the size of Switzerland. It speaks a great deal about the remoteness of the area that it was eighteen months before India discovered the road and only then after it was alerted to its existence by a notice in the Beijing press.

A border war followed. The Indian North Eastern Frontier Army, heavily outnumbered and poorly equipped, were roundly defeated after they were attacked by Chinese forces on October 20, 1962. Subsequently Liu Shaoqi, at the time Mao’s putative successor, said that China “had taught India a lesson and if necessary, would do so again and again.” In essence this has been the historic attitude of China toward India — a populous but rather irrelevant country.

Further border clashes took place in 1967 and 1975. And after China built a road along its side of Pangong Lake in 1999, Chinese “microaggressions” became the norm. In 2019, violent, indeed deadly confrontations took place on the lake and its adjacent hills. An agreement that neither side’s patrols should carry firearms was agreed. However, the arms limitation agreement did not include clubs and iron bars; subsequently the border fights went medieval.

So why has peace suddenly broken out? Chinese politics and its motives are always opaque, but the world has changed since the border dramas of 2019-2020. China is in trouble. Like Japan in the twenty years after its property bubble burst in 1990 precipitating two lost decades, China is facing a similar prospect. Its rapid export-led growth of the first decades of the millennium has come to an end; an economy in which companies have leveraged for double digit growth has now slowed to less than half that rate. In the wake of this deceleration lies a trail of dead property assets and effectively bankrupt provincial governments.

At the same time, Xi’s bellicose threats toward Taiwan, his aggression in the South China Sea and his clampdown on entrepreneurial technology stars such as Alibaba’s Jack Ma has frightened off investors. Foreign direct investment into China is collapsing — it fell sharply in 2023 and is down 29.1 percent in the first half of this year. A long period of deflation looms.

India’s economic path since has been different. Such was the depravity of the socialist economy bequeathed by Nehru and his daughter Indira Ghandi that in the forty years after independence India sank into a state of global irrelevance. As Henry Kissinger said at a lunch I attended in New Delhi in 1995, India, in the post war period, “disappeared” — both in an economic and geopolitical sense. It was only after the collapse of the Soviet Union, with which India was umbilically linked in their autarkic economic policies, that Congress Party prime minister Narasimha Rao was able to liberalize the economy and encourage foreign investment.

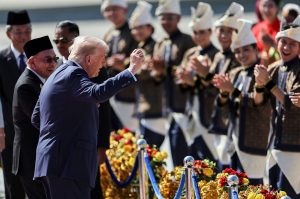

India has now overtaken China to become the fastest growing major economy in the world. Since the accession to power of BJP (Indian People’s Party) Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014, India, for the first time, has begun to be perceived as a world power. Economic growth in the latest fiscal year was 8.2 percent.

To sustain export led growth China needs access to a fast-growing Indian market which boasts 1.4 billion consumers. Meanwhile Chinese manufacturers want to build plants in India. For example, BYD (Build Your Dreams), India’s fastest growing auto company, has been seeking a license to make cars in India for several years. Settling the border issue with India makes economic sense for a China whose hubristic economic bubble has burst.

Modi is in the enviable position of being able to play the world’s superpowers against each other

Does the rapprochement between China and India prior to the Brics summit in the historic Russian city of Kazan, where Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and Modi will likely engage in side-talks, suggest that India will join the informal anti-western alliance that includes China, Russia, North Korea and Iran? Never.

Firstly, agreeing to a standstill in the Himalayas is no big deal. The huge area in play in this Himalayan wilderness is virtually uninhabited and uninhabitable. Clearly neither country benefits from pouring military resources and diplomatic focus on these almost worthless borderlands. Geopolitical rivalry will undoubtedly continue for control of the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. It would be foolish therefore to read too much into yesterday’s announcement.

Secondly and more importantly, whereas Russia, Iran and North Korea need a big-brother China relationship, India sees itself as the equal of China. A subservient role would not work; Modi, the Hindu ultra-nationalist, who is chippy when it comes to his country’s past as a part of the British Empire, is hard-wired for independence.

Moreover, Modi is in the enviable position of being able to play the world’s superpowers against each other. Recently he did so over the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Modi joined in the criticism of Putin, but while the west banned Russian energy, India picked up oil on the cheap. Western leaders were not happy, but they gave Modi a free pass; they too want to benefit from India’s growing economy.

Now that India has shown itself to be on the path to becoming a major economic power — my back of the envelope calculations suggest that its GDP will overtake America by 2050 — it is able to leverage its success. India will ignore the calls to join either the western bloc or the Chinese bloc. As Foreign Minister Jaishankar has said, “I think we should choose a side, and that’s our side.”

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.