No one should be put off reading Patrick Cockburn’s remarkable biography of his father by its misleading subtitle. “Guerrilla journalism” doesn’t do justice to its subject. The suggestion of irregular warfare from the left underrates Claud Cockburn’s great accomplishments in mainstream politics and journalism and doesn’t begin to embrace the romantic and daring complexity of his life and career.

By late 1931, his eyewitness reporting at the start of the Great Depression convinced him that Marx was right

Indeed, it is the journalist son’s signal achievement to have surmounted left-wing cliché and written a fascinating and subtle portrait of a paradoxical career. Claud was a mostly loyal child of the British Empire, who renounced establishment status and comfort (as a distinguished foreign correspondent for the Times of London) for the freedom (as a committed communist on the margins of British journalism) to pursue and describe the most important story of the twentieth century: Adolf Hitler’s mostly unchecked rise to power in Germany and the fascist movement that set fire to the entire world. That Cockburn’s mimeographed newsletter, The Week, in the 1930s became a must-read in the appeasement-corrupted elite that he left behind might well have merited official honors in post-war England; but he had to settle for having been right before almost anyone else.

Conventional distinction didn’t seem to interest Claud, who, Patrick writes, was “above all… a serious revolutionary who wanted to change the world.” More convincing is that Claud was a profoundly skeptical enquirer, whose diplomat father, Henry, imbued him with a sense of right and wrong that made it impossible for Claud to go with the flow. “China Harry” survived the Boxer rebellion and had “no doubts about the British Empire being a force for good,” according to Patrick. But in Henry’s next diplomatic posting, his protests against Japan’s violent subjugation of occupied Korea ran foul of British policy and eventually forced him to return to England. Claud took note, Patrick tells us:

The episode reveals that Henry, who was by far the greatest influence on Claud growing up, was the kind of independent-minded High Tory with an overriding objection to injustice whom his son always liked.

Another influence was Graham Greene’s father Charles, the liberal, politically pessimistic, chess-playing headmaster of Berkhamsted school, who regularly summoned Claud for matches and taught him a view of history that pointed “inexorably toward disaster.” Claud caught up with contemporary history soon enough, in post-1918 Eastern and Central Europe, where resentment and revanchism were rampant. When his father was sent to Budapest by the foreign office, Claud developed an interest in politics and a sympathy for the “victims” of the victorious Allies, including Germany. But his compassion for the losers soon waned.

After Oxford, in 1927, he went to work as an assistant to the Times correspondent in Berlin, where he demonstrated a knack for the news business. A teacher’s report at Berkhamsted had already identified his studies in Latin and Greek as “quick and appreciative,” while warning that he “must not be led away from thoroughness by the facility with which he can turn out work” — effectively, praise with faint damnation. In other words, Claud was a quick study and a fast writer, essential tools for a good journalist, so it’s not surprising that before long the Times’s Norman Ebbutt gave him serious assignments that resulted in scoops.

By 1929, Claud was a rising star at a prestigious newspaper, covering the stock market crash as its New York correspondent and earning the notice of Geoffrey Dawson, the Times’s legendary editor. But while in Berlin, Claud had already fallen into bed, romantically and politically, with the Schwarzwald circle, an eclectic group of anti-Nazi intellectuals, and his earlier communist flirtations (indulged in in England with his friend Graham Greene) began to flower.

By late 1931, his eyewitness reporting at the start of the Great Depression convinced him that Karl Marx was right. Despite Dawson’s entreaties to stay with the paper, Claud had made up his mind that the only story worth his time was the Nazi movement, and he wanted to be where the action was, in a position to do something about it. He wrote to Dawson:

There comes… a point where not to act, or try to act more or less on one’s political convictions, becomes damaging to oneself in some way, and unfair also to one’s employer.

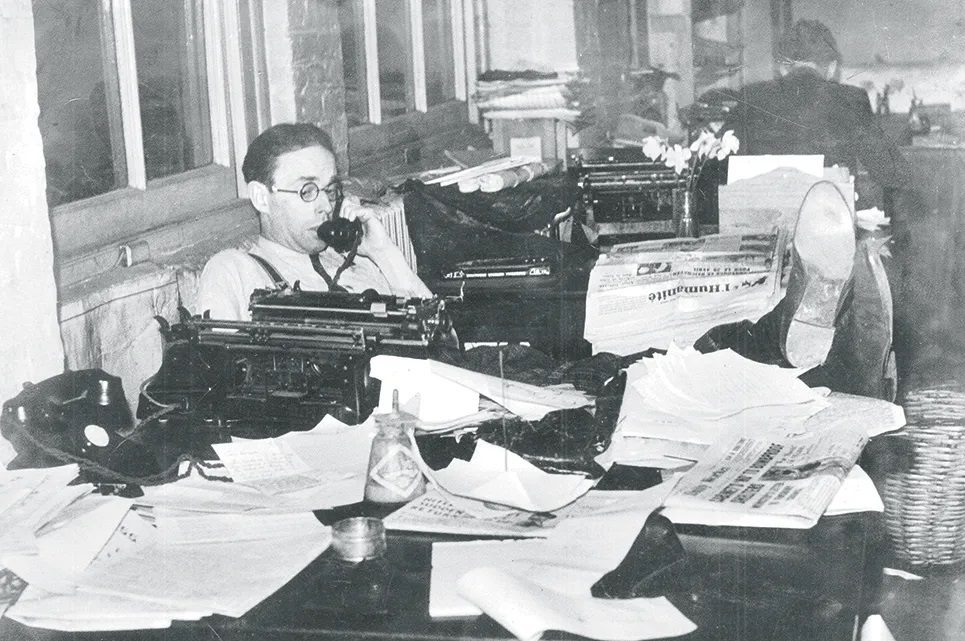

Nazi Germany was too dangerous, so Claud returned to London to found his “one-man band in which all instruments could be played by Claud.” Launched on March 29, 1933, The Week immediately began scooping the competition because there were so few outlets for anti-Nazi Germans, foreign office dissidents and foreign reporters based in the UK to get any news out about Hitler’s repression of political opponents and Jews. As a clearing-house for accurate information about Germany, The Week became essential reading for politicians, civil servants and journalists alike. It also attracted the interest of MI5, whose detailed memos about Claud provide a kind of parallel biography that Patrick astutely employs to flesh out what until now has primarily been Claud’s own version of his life, as told in his bestselling autobiography published in the 1950s.

With a circulation of never more than 5,000, The Week by itself would make a book; but two revelatory stories stand out. In 1934, Claud scooped the world ten days before the Night of the Long Knives by reporting that Hitler was on the verge of establishing a military dictatorship. In 1937, he described for the first time’ the Astor family’s network of friends and associates that he later dubbed the “Cliveden set,” named for the Astors’ country estate, a moniker that became a worldwide synonym for the appeasement of Hitler. Given John Jacob Astor’s ownership of the Times and Dawson’s membership of Cliveden’s collection of high-society fools, this must have been the sweetest of victories for Claud.

In a sense he was overtaken by his own prescience, and he should have quit while he was ahead — in 1940, when Winston Churchill replaced Neville Chamberlain as prime minister. Never a doctrinaire communist, his sense of humor, numerous romantic entanglements and ideological rebelliousness interfered with party discipline. But he was nonetheless blinded by the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact in August 1939. “Churchill’s national coalition,” writes Patrick, “was very like the anti-fascist Popular Front government Claud had advocated.” Claud was “insufficiently aware… that almost everything that he had campaigned for since fleeing Berlin in 1933 was, by the summer of 1941, official British government policy.”

Sadly, to Claud’s and the Churchill government’s discredit, The Week was shut down for toeing the Soviet line of non-confrontation with Germany as late as January 1941. It only resumed publication in September 1942, well after Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union had brought Stalin into the war. The British communists were similarly ungrateful toward their subversive comrade (after all, he had risked his life covering the Spanish Civil War for the Daily Worker.) Once the ban was lifted, the CP leadership hoped “to keep [The Week] closed” because “it was too independent, though widely assumed to be under their control.” As the anti-communist Malcolm Muggeridge wrote:

No God failed [Claud] because communism never assumed a God-like shape in his eyes. He supported it as a cause wholeheartedly and with characteristic verve; and when it ceased to appeal to him as a cause, he ceased to support it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.