West Bank

It’s hard to take someone seriously when they tell you: be extremely careful, that part of the West Bank is just like Gaza now. Hyperbole, surely, but duly noted. It was late August and I was heading to the Tulkarem and Nur Shams refugee camps, two adjacent Palestinian communities in the northern occupied West Bank which are now the site of almost daily fighting between the Israeli military and Palestinian armed groups. The nearby city of Jenin has seen even worse violence.

On the approach to Nur Shams, the landscape suddenly turned from an impoverished yet benign Arab countryside into a full-blown urban war zone. Dust filled the air, Hamas propaganda was plastered all around, an Israeli drone circled above us. A teenage boy loitered nearby, muttering something into his walkie-talkie. Small clusters of sullen men sat on the side of the road, smoking cigarettes next to their destroyed shops.

The Israeli bulldozers had left a ruthless trail of destruction. The main roads and dozens of buildings had been destroyed. Raw sewage was flowing into the street. The resemblance to Gaza was indeed uncanny. But hell is a bottomless pit — no matter how bad things may seem, they can always get worse — and they are here.

On August 28, the Israeli military launched its largest military operation in the occupied West Bank in more than two decades. It lasted ten days and involved thousands of troops.

“We must deal with the threat just as we deal with the terrorist infrastructure in Gaza, including the temporary evacuation of Palestinian residents and whatever steps are required,” said Israel’s foreign minister Yisrael Katz that day.

The Israeli government seems intent on the Gazafication of the area — and the process is already well underway. Israelis should know what their government has signed them up for. Hamas and other radical groups are quickly filling the vacuum Israel has created by weakening the Palestinian Authority, which is now on life support.

One morning in late August Khalid Sayes and his family in Nur Shams were awoken to the sound of an Israeli helicopter landing on their rooftop. Shortly thereafter, Israeli soldiers broke down the door and locked them all in a nearby room. Then they turned his third floor into a sniper lookout. It wouldn’t be the first time.

“They would knock on the door, and if we didn’t open it, they would blow it up,” Sayes said, standing over his freshly repaired floors. “Look at the tiles here, they would place their weapons on it, sleep and shoot from here and then leave… they broke everything,” he said.

What he’s describing is a “straw widow” operation, a frequently employed tactic of the Israeli military. “When you serve in the West Bank and Gaza, you are inside Palestinian cities and towns. But more than anything, you are inside Palestinian homes,” explains Nadav Weiman, a former Israeli sniper.

When conducting a straw widow operation, “if one of the family members wants to eat, to drink, to take medicine, go to the bathroom, they need authorization from us. Because it’s our house, it’s not their house anymore.”

The flat is a strategic location for the Israelis, Sayes acknowledges. From each of its windows, the snipers could see several strategic targets: a nearby school, the town square. Sayes had repaired most of the damage in his home, but he was very aware this could be in vain. Indeed, just two days later the Israelis were back to raid the camp again.

Just down the street in Tulkarem, UN employees tried feverishly to repair some drainpipes ruptured by Israeli bulldozers. No one seemed to be under any illusion that the violence was over, but all they could do was hope and work.

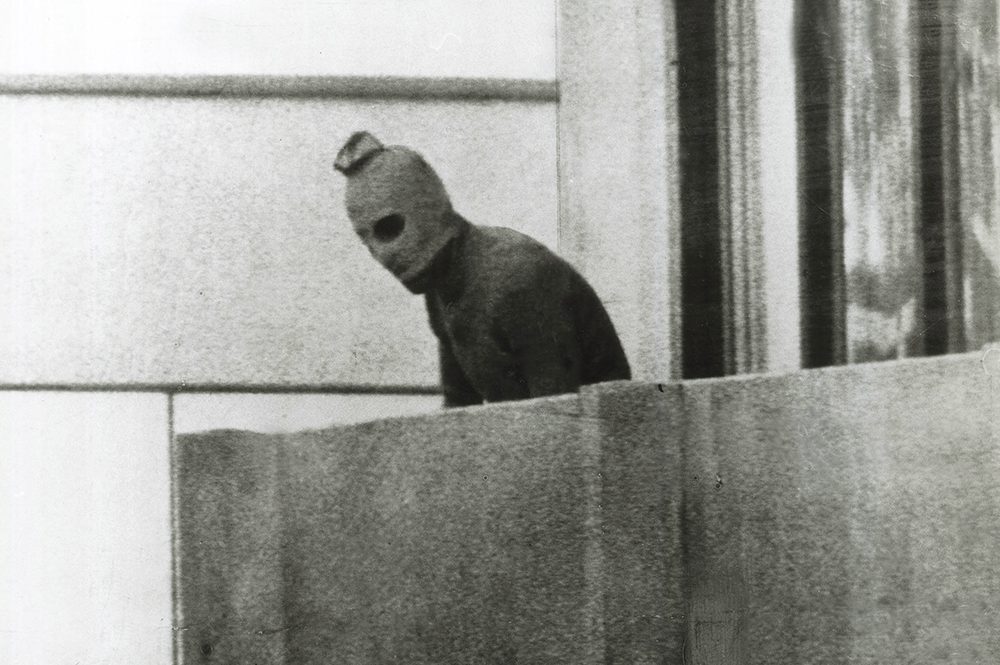

In the inner sanctum of the Tulkarem camp, the militants were keeping busy in a different way. Black tarps had been fastened to the top of the buildings and stretched across the narrow streets and alleyways. A precaution against drones, I was told, to conceal their movements.

Back on the main road, a UN official directed me to the site of the previous day’s drone strike. The father of the deceased, a fighter in Palestinian Islamic Jihad, was there to explain. A pile of cinder blocks lay where his son once stood.

According to Shaiel Ben-Ephraim, a former Israeli diplomat and political commentator, the fighters in Tulkarem and nearby Jenin are mostly hardened terrorists, and the violent resistance does not have grassroots participation.

“These aren’t organic organizations. The reason for that is because people in the West Bank generally look at their lives, look at what’s happening in Gaza, and say you know what? I don’t want that. It could be a lot worse,” he said.

But as Israel continues to collectively punish the Palestinians, it can only expect an equal and opposite collective resistance. Ben-Ephraim says organic recruitment for radical groups in the West Bank is still embryonic, but to me it seemed to be in full swing.

“I think much of what we can see in the form of violent resistance from Palestinians can best be described as [coming from] desperate people who feel they have little or nothing to lose,” said Paul Pillar, an academic and retired CIA analyst, in an interview with The Spectator.

After ten days of intense fighting, the Israeli military withdrew from Tulkarem, Jenin, Nablus, and other nearby areas on September 6.

“We had numerous invasions in the past, but this invasion is the most destructive,” said Jenin’s governor, Kamal Abu al-Rub. According to the Palestinian Authority, thirty-nine Palestinians were killed and more than 145 injured between August 28 and September 5. In a statement to The Spectator, the Israeli military said that one of its soldiers had been killed in the same period.

“Since the October 7 massacre, there has been a significant increase in terrorist attacks in Judea and Samaria and the Jordan Valley area, with over 2000 attempted attacks occurring since the beginning of the war,” a spokesperson for the Israeli military said.

Israeli forces say they killed dozens of fighters affiliated with Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, including senior leaders in Jenin and Tulkarem during the summer operation. But as a Hezbollah boy scout once told me in Lebanon, “Even if Mohammed is dead, a hundred Mohammeds are born every day to take his place.”

On September 6, undeterred Palestinians, many of them armed, flooded the streets of Jenin to honor those who fell during the operation. A few days later, Palestinian Islamic Jihad released a video showing what appears to be dozens of heavily armed fighters marching through the city.

Jenin and Tulkarem are part of “Area A,” a section of the West Bank which is supposed to be controlled by the Western-backed Palestinian Authority, per the Oslo Accords. The PA works with Israel to disrupt radical Palestinian groups and is the international face of the Palestinian nation. But around 2018, the PA started losing control of these areas, Ben-Ephraim says. “Over the last few years, the Israeli government has made efforts to undermine the PA by depriving them of their own tax money, tacitly supporting settler terrorism and making deals with Hamas instead of them,” he said.

Ben-Ephraim clarifies his position: this isn’t a problem that just Israel has created. “Iran has been trying to destabilize the West Bank for years now… but Israel is letting them in by not buttressing the main block to their influence, which is the PA.”

A lot of “foreign money” has been penetrating the West Bank as well, resulting in Palestinian armed groups gaining the capacity to create “more powerful and sophisticated improvised explosive devices,” a senior UN official told The Spectator. That certainly appeared to be the case in Nur Shams, where during my visit I saw a massive IED crater at the entrance to the camp. This one went off accidentally, but just down the road, there was another from earlier in the summer, when an IDF bulldozer ran over it, a local man said.

The last year has been the deadliest on record for Palestinians in the West Bank since the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs started tracking casualties in the region in 2005. Between the attack on Israel on October 7, 2023 and September 23, 2024, 693 Palestinians and eighteen Israelis were killed in West Bank fighting, according to the OCHA.

As Israel operates with increasingly indiscriminate force in the West Bank, support for the PA and nonviolent resistance more generally is plummeting.

According to a poll published in June by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, 94 percent of Palestinians in the West Bank want PA president Mahmoud Abbas to resign. The same poll found that 54 percent of Palestinians prefer “armed struggle” to end Israeli rule, while only 16 percent opt for “nonviolent resistance.”

In the West Bank in June, 41 percent of residents said they support Hamas, compared to 35 percent in March, while 17 percent support Fatah, the armed wing of the Palestinian Authority, compared to 12 percent in March.

“A consistent goal of the Netanyahu government has been to keep the Palestinians sufficiently divided, so that Israel can say it doesn’t have an interlocutor when it comes to peace negotiations,” said Pillar, the former CIA analyst.

Everyone in the Israeli government knows they should be working with the PA, Ben-Ephraim says. But doing so would be politically untenable, and would lead to the radicals, finance minister Bezalel Smotrich and national security minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, breaking up Netanyahu’s coalition.

“It’s going to get much, much worse. As Israel keeps raiding these areas, the Palestinian Authority loses legitimacy, Hamas will keep getting stronger,” Ben-Ephraim said. “Long term, I think odds are the PA is going to collapse.”

What then, is Israel’s strategy in the West Bank? The Israeli military ignored multiple requests for comment to this question.

“They didn’t tell you what the strategy is because they would be embarrassed to say there isn’t one.” Ben-Ephraim said. But it also isn’t the military’s job to be in charge of a strategy, he agrees. A real strategy would require pursuing political and diplomatic solutions that complement the use of military force.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply