Is it ironic to give a prize for encouraging “open discussion and debate in the classroom” and “creating an environment where all perspectives can be heard” in the name of William F. Buckley Jr.?

Although best known today as the founder of National Review and longtime host of Firing Line, Buckley first came to prominence in 1951 with the publication of his book God and Man at Yale, subtitled: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom.ˮ

Buckley’s secular and secularized Protestant critics might well have considered the firmly Catholic young man, twenty-five years old at the time the book appeared, an apologist for something they regarded as superstition. But Buckley did not mean the term as a compliment when he applied it to academic freedom. On campus or off — his second book was a defense of Senator Joseph McCarthy — Buckley was an opponent of liberalism’s “open society” ideal.

Yet the Buckley Institute at Yale, which was founded in 2011 by undergraduates who wished to honor the memory of the illustrious right-wing alumnus, who died in 2008, now awards an annual Lux et Veritas Faculty Prize to a teacher who supports “open and civil discussion in the classroom even on contentious issues,” as a news release on the political science department’s website puts it.

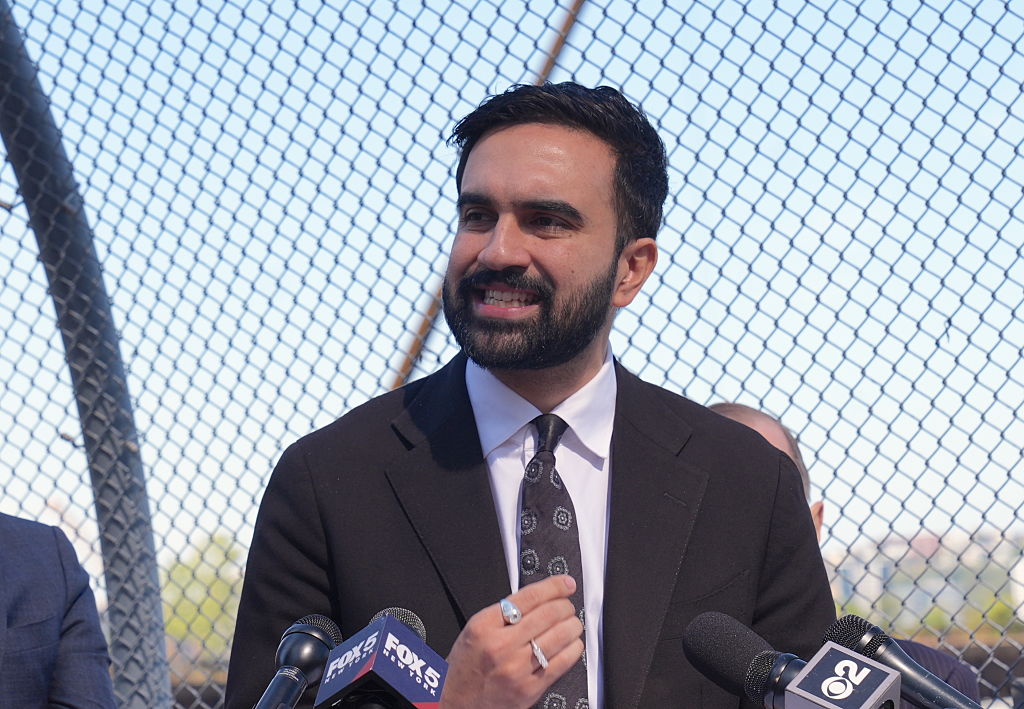

The irony is deeper, however. Buckley — like his mentor, the cantankerous Yale political science professor Willmoore Kendall — advanced intellectual freedom by challenging it, while many of its self-proclaimed champions have bred, or indeed imposed, stifling orthodoxies. In any event, the lecturer who received this year’s Lux et Veritas award, Gregory Collins, is by all accounts a teacher who inspires students to speak their minds civilly yet freely, as well as being a rare conservative at an institution that has only become more boringly left-liberal in the decades since God and Man at Yale. Collins’s own first book, Commerce and Manners in Edmund Burke’s Political Economy, is a scholarly work that any student of Burke and his time can admire, regardless of ideology.

At the ceremony honoring Dr. Collins I spoke to faculty who were on the political left yet greatly appreciated the diversity of thought that the Buckley Institute and conservatives like the honoree bring to the campus. A question high on the mind of one professor was why the students of today are so passive in the classroom, shunning even disagreement, to say nothing of intense debate. He noted their habit of preemptively apologizing any time they contradicted someone else or expressed a difference of opinion. This wasn’t the way earlier generations, raised in an outwardly stricter America, spoke in class. What changed?

The older professor and I considered a few possibilities, including the effects of pervasive anti-bullying campaigns, which in practice allow administrators to bully young people from kindergarten onward. A right-winger might see a parallel with the way government power always expands in the name of protecting the disadvantaged or oppressed — whose disadvantages and oppressions remain as other citizens’ wellbeing and freedom are sacrificed.

A few weeks later a younger academic from a university in Washington, DC suggested to me a new element that aggravates the problem massively: the cellphone camera. Students today, this professor suggested, are terrified of being recorded saying anything out of step with progressive orthodoxy. Speak up in class, and the internet may soon hear of your heresy.

The classroom has become a panopticon, a setting much like Jeremy Bentham’s imagined prison, in which every inmate’s words could be heard and actions observed at all times. And the students themselves are the jailers and prisoners alike. In any class, anyone could turn informant at any time. The professors, too, fear the watchful, censorious student eye.

The perversity of this would take George Orwell’s breath away. Socialist that he was, Orwell might experience a touch of relief, on top of abject horror, at this vigilante totalitarianism. No central Big Brother has his eye on these Winstons and Julias. They’re all just infant brothers and sisters eager for the approval of the online herd, a collective nanny. Amid post-Cold War capitalist triumph, America’s rising generation behaves like Stasi informants, thanks to an ubiquitous consumer product and a post-Communist left-wing mentality. Most students may not be tattletales and spies, but enough are to keep the others in line.

Conformism as a byproduct of egalitarianism has long been a national defect. “Freedom of opinion does not exist in America” was already Alexis de Tocqueville’s verdict nearly 200 years ago.

“In that immense crowd which throngs the avenues to power in the United States,” the Frenchman observed in Democracy in America, “I found very few men who displayed any of that manly candor and that masculine independence of opinion which frequently distinguished the Americans in former times, and which constitutes the leading feature in distinguished characters, wheresoever they may be found.”

Courage, like every virtue, requires practice. College classrooms, havens from the tyranny of everyday opinion, are training grounds for intellectual courage — something influential citizens and leaders in a free country must have in abundance. America’s elite has been cowardly and conformist for too long, with effects that are only too obvious. Yet classrooms today threaten to make the malady worse, at least without the efforts of teachers and challengers like Collins, Kendall and Buckley.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply