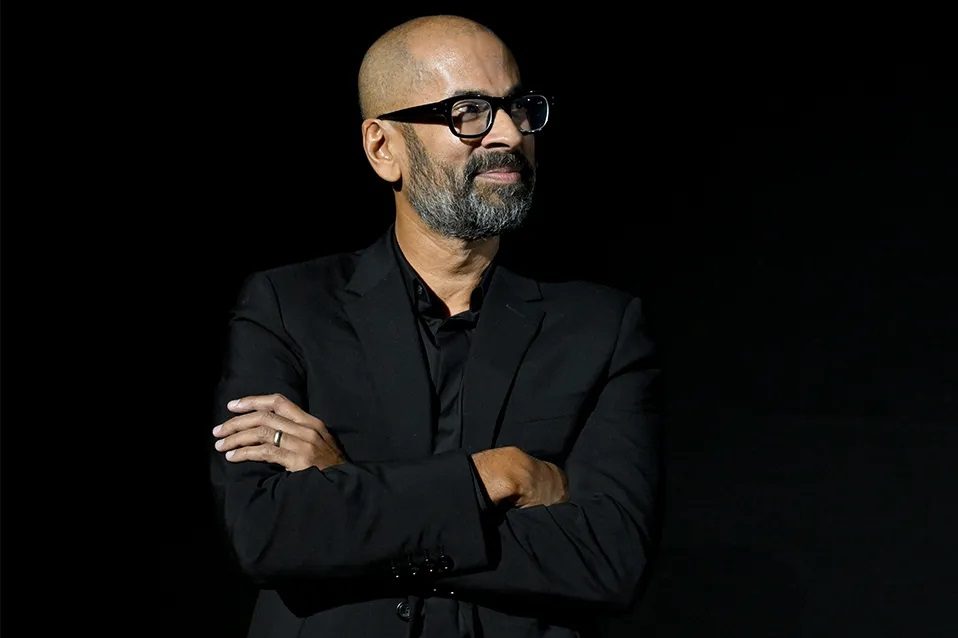

Money can’t buy you love, the Beatles sang. But that doesn’t matter so much if you’re not interested in love, like Brooke Orr, the thirty-three-year-old heroine of Rumaan Alam’s fourth novel, Entitlement. In contrast to Alam’s wildly successful, lockdown-resonant Leave the World Behind, the latest book is set in 2014, during the era of “Obama’s Placid America,” a world depicted as a virtually frictionless pre-Trump utopia in which “black, gorgeous, serious, passionate” young women such as Brooke can thrive. When she leaves her teaching job and joins the charitable Asher and Carol Jaffee Foundation — started after the benign octogenarian billionaire Asher Jaffee lost his daughter — she realizes that money is where her heart lies. Yet Alam is at pains to investigate why Brooke Orr (and the auric resonance of her surname is surely intentional) is not straightforwardly avaricious.

She is adopted, with a white mother, and two white siblings, and while she appears confident, a worm of insecurity gnaws at her constantly: “Her own mother… had not wanted her. Who then ever would?” In this respect she resembles a Jamesian or Whartonian heroine, making her way in a grown-up world that she barely understands, unaware of her real motivations.

Her job at the foundation is to find “money for people who deserved it,” and she sets about this with gusto, attempting to give a sizable donation to a children’s dance school. But her philanthropic impulse is complicated by being suddenly immersed in the world of the super-rich, depicted as gods gazing down from Olympus. She loves setting down “the mint-green corporate card with a satisfying little snap of plastic on wood,” or salivating over the Monet in Jaffee’s penthouse. What she really wants, however, is a simple stake in adulthood. Having never felt entitled to anything, she becomes convinced she deserves the things the previous generation took for granted: her own home, job security, even family life.

Of course, in a novel a sense of deserving what you see as your due is dangerous. It can lead to terrible decisions. Alam is canny enough to wrongfoot the reader by characterizing both Brooke and Jaffee against type. Though Jaffee entertains romantic fantasies about Brooke (despite her being a surrogate daughter), he’s not a predatory, privileged older male. And while Brooke acknowledges her mentor as the father figure she never had, she still dreams of a slice of his unimaginable wealth. The two circle each other for more than 200 pages before the final, inevitably explosive, confrontation.

Written with Alam’s customary alertness to how small details (witness the “fist-sized muffins of grated carrot, coconut, sunflower seed and date” baked by Jaffee’s personal chef) can reveal a whole life, Entitlement is an engrossing exploration of the pitfalls of privilege and philanthropy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.