There has been a spate of books recently about private education, ranging from academic denouncements of their malign effects on society, such as Francis Green and David Kynaston’s Engines of Privilege, to Charles Spencer’s grim chronicle of neglect and abuse, A Very Private School. Though technically falling within this genre, 1967, the singer-songwriter Robyn Hitchcock’s diverting account of his formative spell at Winchester College, seems to hail from a rosier era. It is one where matron’s buttered crumpets rather than bullying were the chief topics of Billy Bunter-esque reminiscences that proclaimed schooldays the happiest of one’s life. Indeed Hitchcock even wonders whether his parents got their “money’s worth,” since, contrary to expectations, he was not “beaten up, sodomized or ritually humiliated by the other inmates.” He seems almost disappointed in retrospect that nobody stuck his “head down a toilet bowl” or “stripped and mocked” him.

Instead, Winchester, or more specifically the communal gramophone in his school house, was to give Robyn (born in 1953) the musical marrow to suck on that has provided him with a decent income for close to half a century. It was there that Bob Dylan, the post-moptop Beatles, Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix and the Incredible String Band all came his way. The chorus refrain of “How does it feel / to be on your own?,” from “Like a Rolling Stone,” heard blaring from the house gramophone shortly after he was deposited at school by his parents, made him an instant Bobcat convert. Dylan, he felt, seemed to be addressing him personally — those lyrics speaking to his own sense of “being marooned alone in an alien world.”

Nevertheless, having grown officer-class tall by the autumn term of 1967, he worries about being unable to look up to his idol, who is now “nearly a foot shorter” than him. And his worst fears are soon realized when this mythic year slips away and Dylan returns in 1968 with John Wesley Harding, after a prolonged silence and rumors of a motorcycle crash. This country rock album recorded in Nashville, Tennessee, Hitchcock characterizes (rather unfairly to my admittedly state school-educated oik’s ears) as “flat, beige and not much fun to listen to.” Yet, ironically, Hitchcock himself would wind up both living and recording in Nashville.

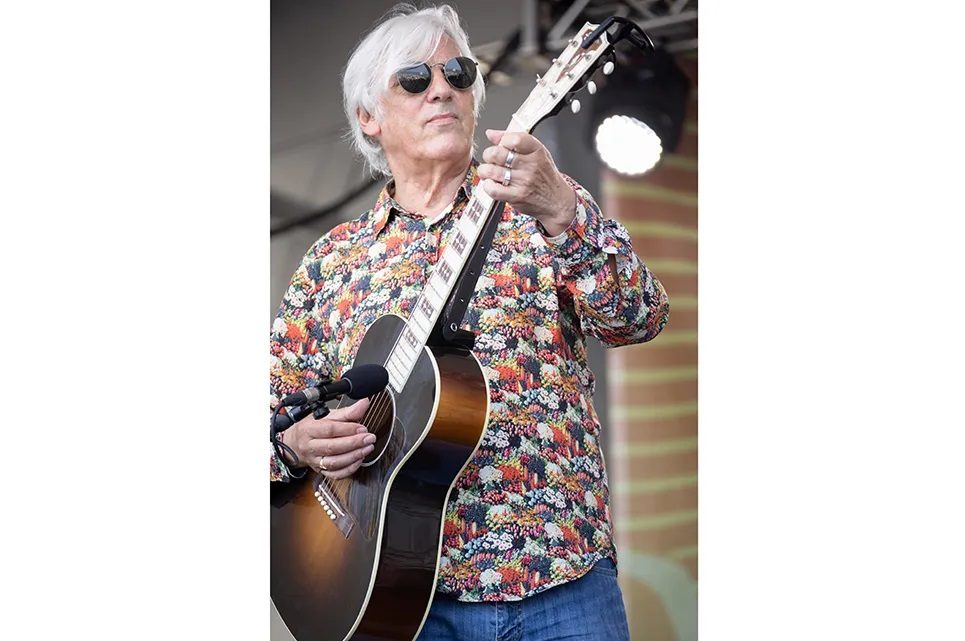

Few British artists have been quite so feted stateside but largely ignored at home as Robyn Hitchcock. Cited as an inspiration to REM and Yo La Tengo as well as a mainstay of American college radio stations since the 1980s and the subject of a live concert film by Jonathan Demme. Hitchcock initially came to prominence in the late 1970s as the lead singer of the Soft Boys. A Cambridge-based post-punk outfit, they were considered a little too enamored of the Byrds to be taken seriously by a UK music press then championing the northern gloom of Joy Division. They split up in 1981.

While the band’s former lead guitarist Kimberley Rew, a Jesus College archeology graduate, would go on to enjoy success with Katrina and the Waves, penning the FM radio staple “Walking on Sunshine” and their 1997 UK Eurovision winner “Love Shine a Light,” along with “Going Down to Liverpool,” a hit for the Bangles, mainstream fame has mostly eluded Hitchcock. He has always worn his 1960s influences on his sleeve, following a determinedly narrow path of literate, psychedelia-tinged folk rock that has earned him a devoted following and the admiration of similarly singular peers such as Nick Lowe and XTC’s Andy Partridge, with whom he has collaborated.

The book makes clear what was previously only sonically implicit, offering more than a few join-the-dots moments. Familiar Hitchcockian obsessions — fish, cheese and public transport — are present, as is an admission to being on the autistic spectrum. There are also wonderfully surreal turns — an imagined conversation with a lager-lime-drinking Dylan about the New Vaudeville Band’s novelty number “Winchester Cathedral” among the comic set pieces.

We encounter, too, a young Brian Eno, the former Roxy Music man and record producer, then a teacher at the nearby art school but seemingly already making waves locally as a convener of groovy happenings. And there are affectionate if unsentimental portraits of Hitchcock’s parents, whom he credits with instilling in him a love of words. From his father, Raymond, he also inherited a mania for drawing. A taciturn veteran of the second world war injured in the D-Day landings, Raymond was an engineer turned would-be Francis Bacon who went on to write the bestseller Percy, eventually adapted into a sexploitation romp starring Hywel Bennett in 1971. Hitchcock’s mother, Joyce, an avid reader (whose family money helped bankroll Raymond’s artistic ambitions), introduced Robyn to William Faulkner and bought him his first guitar and LPs by Bert Jansch. They, of course, also sent him to the same school as our former prime minister Rishi Sunak, a self-declared Taylor Swift fan, although with notably different results. But then you pays your money and you takes your chances.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply