Human risk assessment is not a dispassionate numbers-crunching game. Those who fear flying have to know we’re four times more likely to die in a car crash than in a fiery plunge from the skies, even if we’re boarding a Boeing. The fear of flying may be common, but only a select few will rule out the jet engine entirely. When it comes to emotional risk evaluation, there is one area where phobia prevails over reason: our increasingly sterile view of what constitutes a good bet when it comes to marriage and family life.

Since the second half of the twentieth century, American society has been on a mission to eliminate risk. Seatbelt and helmet laws reduced deaths in automobile and bike accidents at the expense of comfort and self-respect. I’m less certain about the upsides of the replacement of mulch with that weird squishy plastic that has made playgrounds feel so grimly utopian, but I suppose there are fewer of those nasty knee splinters. The retreat from risk isn’t in your imagination; survey data consistently shows “kids these days” are less likely to drink, less likely to drive and less likely to screw in the back seat.

There appears to be a measurable psychological break in the mental fragility of people born before and after 1995, according to astute data-crunchers like Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge. But the risk-averse bubble didn’t start and end with the elimination of mulch.

According to a 2023 report from Pew Research, a quarter of forty-year-olds today have never been married, a record high that is the result of a steep climb starting in 2010 as the youngest Gen Xers and the oldest millennials started hitting forty. Childlessness is up as well — the larger driver of the fertility plunge is not families having two kids instead of three, but the fact that larger numbers of American adults are not forming families at all.

Even for those who are getting married, what was once a rite of passage and a leap into adult life — something that held some measure of thrilling risk — has become more of a capstone, considered responsible only after one checks the appropriate boxes of preparatory life coursework.

There are at least three sources — or rationalizations — for this risk-averse attitude toward love and family, embodied by those I’ll call the leftist Go-Bag Girls, the Red Pill Divorcées and, probably the largest and most important of the three, the Millennial Avoiders.

The Go-Bag Girl mentality is not exclusive to women, but because women are the presumed victims of modern culture (despite being you-go-girl cheered from birth, getting the majority of higher degrees and living longer than men), this supposedly rational advice is usually directed their way. Stoking women’s fears of letting go of their corporate qualifications, the Go-Bag Girls spin stories, many of them very real, about the foreclosed career possibilities for stay-at-home-mothers and wives who find themselves alone after a husband’s misdeeds, unable to jump back into the working world.

These sermons are generally delivered by women who have been through the wringer, but they are often driven viral by millennial girlbosses shuddering at the mere possibility of encountering the wringer at all. The self-reassuring implication is that it’s wildly risky to make yourself financially dependent on a man.

And it’s not just financial preparation that’s becoming part of the modern woman’s back-up plan. TikTok is full of videos urging girlfriends and wives to keep a secret go-bag stashed with cash, food and essentials in case a man who previously showed no signs of abusive behavior turns into Mr. Hyde overnight. The message is simple: vulnerability, financial or otherwise, is akin to base jumping for the dating set.

It’s hard to refute that there’s some truth underlying these warnings. It’s true, for example, that taking a twenty-year hiatus to raise children isn’t good for your résumé. That wage gap feminists are always banging on about isn’t attributable to discrimination, but rather the different choices women make about career and family while their children are young. What feminists see as injustice is really the intersection of biological reality, sex differences and free choice. This oppressed class of women are oddly silent in public discussion. It is almost as if the wage gap studies are designed to scare women out of entering into the relationships that might render their go-bags unnecessary.

These lonely women have ready allies at the opposite end of the horseshoe. If the Go-Bag Girls complain that divorce after tradlife leaves women destitute, the Red Pill Divorcées warn young men that marriage is a financial racket in the opposite direction. “Seventy percent of divorces are initiated by women,” say the Andrew Tates and Pearl Davises of YouTube, “you’ll be broke, and she’ll be shacked up in the home you paid for with a new guy.” Again, there’s more than a little truth to these warnings. Family courts are often unfair to men, and there’s no doubt that the Eat, Pray, Love cultural messaging reflects a real willingness on the part of many women to throw off the alleged shackles of a marriage in order to pursue a second youth. If Don Draper was the face of the stereotypical mid-century midlife crisis, Betty Friedan matched him for female ennui.

The Go-Bag Girls and Red Pillers are bunkering down for some imagined World War of the Sexes, but the quiet quitters of family formation may be the most alarming of all. The Millennial Avoider is bearing the consequences of when the Drapers and Friedans gained cultural supremacy during the “Me Decade.” Most of us have heard some version of this from friends or family: “I don’t want to go through what my parents did; I’d rather never get married than marry the wrong person and get divorced.” Sometimes cloaked in more irritating therapeutic terms like “cycle-breaking” or “trauma,” the bottom line from many people in their twenties and thirties is that the downsides of a bad marriage, or a broken one, are too high a risk to bear, and that it’s better to avoid the institution altogether. Here are some Millennial Avoider responses to a recent tweet about how divorce affects many adults in our generation well into adulthood:

“Huge, made a lot of zoomers and millennials want to avoid it, so much they’re adverse to getting tied down at all.”

“Divorces are like one bad season in the sports franchise of a boomer’s life. Then on to the next one.”

“What I remember from growing up in the 90s was this cavalier attitude towards divorce, single parenthood and absentee fathers, not just in our lives but in media (i.e. Frasier, Ross from Friends). It was so gross that it made us too careful about getting into marriage.”

If boomers — the primary parenting generation of millennials and the latter half of Gen X — have a more lackadaisical attitude toward the risks of divorce than their kids, it’s because they’re the most prolific practitioners of it in American history. Not content with notching the highest divorce rates in their youths, during which the legal loosening of no-fault divorce laws was followed swiftly by its social normalization, the generation is now pioneering “gray divorce.” Divorce rates among those over sixty-five have tripled since the 1990s, which may explain why nursing homes have gotten simultaneously very lonely and very STD-ridden.

But what about their children, for whom “free love” was not so much a rebellion but a bequest? Millennials are passing judgment with their actions instead of their words. The divorce rate in my generation is lower than that of my parents, a superficially positive number that only reflects an even more depressing reality: we’re not getting married in the first place. Because it is safer.

The discussion around marriage and family consequently ends up as blind as the notion that never seeing grandma for three of her precious last years was somehow more responsible than risking Covid. If we’re going to do the bloodless number-crunching on family formation, it should reflect the risks inherent to the choice of forgoing, out of fear, the single most important source of meaning and happiness in life.

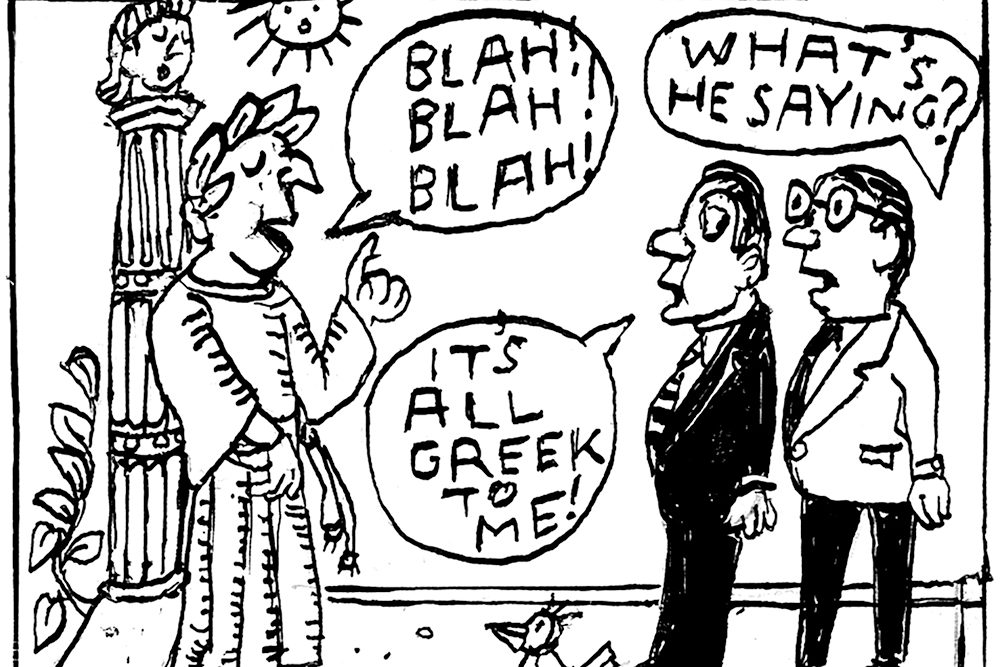

The Go-Bag Girls and Red Pill Divorcées tend to focus on the financial risks of divorce — as though dollars and cents are the primary, or even the only, devastation of a failed marriage. The same blind-man-with-the-elephant risk assessment is being applied to the more important risks to vulnerability and happiness. The emotional wreckage of divorce can’t be presented in a vacuum but must be compared to the increasingly common alternative of living life alone.

According to the General Social Survey, the single biggest predictor of happiness in America is a happy marriage. Married men live an average of nine years longer than unmarried men, contra jokes about men kicking off first just to avoid their wives’ nagging. And no group of women report higher happiness than married mothers, who are 50 percent more likely than their childless single peers to say their lives have meaning.

As for kids, there are few conclusions more obviously backed by social science than the fact that living under the same roof with your married, biological parents until age eighteen confers enormous benefits (in leftist lingo, “privilege”). We’ve known about the uphill battle children out of wedlock face since at least 1965 with the Moynihan Report, but the struggles of children of divorce also show up in the data. While there’s still a great deal of emotional energy invested in denying divorce’s ill effects on children, some studies show them to be larger than the impact even of death of a parent.

The risk of divorce itself is less roulette wheel, more poker — it’s a game that includes some luck, sure, but also lots of factors within the player’s control. The idea that abuse, infidelity, or other marriage risks fall out of the clear blue sky one day may be psychologically comforting, but the statistics don’t bear it out. Religiosity, worldview and commitment at outset all bring down the chances of ending up divorced. The oft-cited statistic that one in two marriages fail is no longer true as divorce-happy boomers age out; more often than not, couples who take the plunge make it out the other end.

Loneliness is the scourge of the modern age. It increases the risk of dementia, stroke and heart disease by a third to a half. A broken heart can literally kill you; a lonely person with heart disease is four times more likely to die an early death. For some reason, our modern culture calls us to loneliness. In the name of safety.

Number-crunching doesn’t really get at the heart of the problem, which is that avoiding marriage and family out of fear of their risks is like going through life with a condom on, literally and metaphorically. There are no guarantees in life, and if you need one in order to reach for something worth having, you’re chicken.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply