NATO’s summit in Washington, DC will be full of pomp and circumstance. The gathering, from July 9-11, is intended in part to celebrate the Alliance’s seventy-fifth anniversary, a symbolic and emotional event for the leaders in attendance. You can expect the red carpet to cover the entire city. Dozens of speeches will be given about how NATO is the oldest and most successful military alliance in history and why the bloc remains a crucial check on Russian expansionism. Some will even claim matter-of-factly that NATO enlargement over the last twenty-five years — NATO has doubled its membership during that period of time — was sound policy and had nothing to do with Russia’s decision-making calculus on Ukraine.

There will be another consistency with past summits: debate over Ukraine’s prospective membership in NATO. The question has hung over the entire alliance like a bad cold since 2008, when NATO, at the persistent urging of President George W. Bush, agreed that Ukraine will eventually become a member. That declaration was a compromise between the US and countries like Germany and France who were far less eager to bring the Ukrainians into the club.

In the sixteen years since, NATO members have deliberated among themselves about when — or if we’re totally honest, if — Ukraine should join. France, one of the holdouts in 2008, is now far more supportive of Ukraine becoming NATO’s thirty-third member. Germany, Europe’s economic engine and biggest military spender, remains hesitant. The United States, too, isn’t exactly gung-ho about the prospect, even if senior US officials like secretary of state Antony Blinken and defense secretary Lloyd Austin repeat the refrain that Ukraine’s future is in NATO. “Ukraine will become a member of NATO,” Blinken insisted back in April. “Our purpose of the summit is to help build a bridge to that membership and to create a clear pathway for Ukraine moving forward.”

For Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, preparing for yet another summer of war, these statements aren’t much consolation. It’s no secret that the actor-turned-wartime commander-in-chief isn’t thrilled with the way the alliance has conducted itself on this issue. He would have preferred NATO offered membership to his country yesterday and hasn’t been sky in expressing it. Last summer, Zelensky lashed out at NATO heads of state for refusing to set a concrete date for Ukrainian membership, calling it “unprecedented and absurd.” The histrionics cast a cloud over the entire meeting. Jake Sullivan, Biden’s loyal national security advisor, gave Zelensky a stern rebuttal, rightly telling the Ukrainians that the United States deserved gratitude, not lectures (he was even more forthright to Zelensky’s aides behind the scenes).

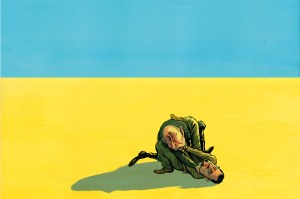

Yet in a way you can’t blame Zelensky for any of this. His country, after all, is still getting hammered by a torrent of Russian ordinance. Tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of people have been killed since Russian president Vladimir Putin launched the war in February 2022. About one-fifth of Ukraine is occupied by the Russians, and despite the fact that the Ukrainian army is holding its own against a superior adversary, they have yet to recapture any notable ground since November 2022.

The blame, rather, should be put on Washington and European capitals. It has been abundantly clear over the last two and a half years that nobody in the West besides the Poles, the Estonians and the French want to even go down the road of courting conflict with Russia in order to save Ukraine. The Europeans may frame the war as some epic contest between civilization and the forces of darkness, but none of them are willing to deploy their own troops into the fight or bear the formidable costs such a decision would bring. Indeed when French president Emmanuel Macron left the door open to sending European trainers to Ukraine, his colleagues — German chancellor Olaf Scholz foremost among them — wasted no time swatting that proposal down as borderline ridiculous and unworkable.

The Americans, too, have no intention of fighting the Russians. For all its talk about helping Ukraine win the war militarily, the Biden administration has opted to make decisions in an incremental fashion so as to limit the possible blowback from Moscow. While it’s true that previous red lines on the delivery of certain US weapons systems to the Ukrainians have been erased over time, it’s also true that Biden seems to understand that Russian escalation is a legitimate concern. If there is one red line Biden is unlikely to cross, it’s turning the US into an active combatant.

It goes without saying that bringing Ukraine into NATO would, de-facto, create the very war with Russia the US and Europe don’t want to fight. And yet US, European and NATO officials keep using robotic, cookie-cutter language in press conferences and joint statements about Ukraine’s imminent membership. Ukraine has turned into the gerbil on the hamster wheel, and NATO is the cruel owner dangling the carrot that’s always out of reach.

Zelensky deserves honesty. So does Ukraine. If NATO was being honest, it would tell the Ukrainians that NATO membership is out of the question. The unanimity required to get it simply isn’t there. Nobody wants to plunge into World War Three or, god forbid, expand the war beyond Ukraine’s borders. And as important as it is to punch Putin in the nose for violating the core tenants of international relations — state sovereignty and the sanctity of national borders — Ukraine is frankly not the center of the universe. This tough but necessary language would at least give Ukraine the opportunity to strike other arrangements for its own security and focus on fulfilling the bilateral defense cooperation agreements Kyiv has signed with multiple European countries to date.

Unfortunately, what we’re likely to get during the summit in a few weeks are the same old hacky phrases.

Leave a Reply