Ransomware, the locking up of large networks through hacking until payment is made, is exploding. Recent attacks have crippled more than 200 city and local government networks in Baltimore, Albany and Atlanta, while specific hacking tools have been successfully used against mortgage companies, universities, hospitals, banks and consulting firms.

A report this month from the cybersecurity firm, Emsisoft, reveals that the cost of ransomware in the US last year was over $7.5 billion, involving 113 state and local governments, 764 health care providers and 1,233 schools. In 2018, the FBI received reports of 1,500 ransomware attacks (the latest available FBI figures) which does not include hundreds of attacks that were never reported with ransoms secretly paid. This is set against a wider background of a massive expansion of cyberattacks using all available techniques. Crowdstrike, one of the world’s largest cyber defense companies, recorded 90 billion threats per day across 176 countries compared with 240 billion the following year or up to 3.8 million threat events every second.

One ransomware attack in Texas locked up the networks of 22 different cities at the same time so that traffic tickets had to be written by hand and payrolls managed as if computers had not been invented. The town of Lake City, Florida paid a ransom of $460,000 in Bitcoin as a cheaper option than rebuilding its network from scratch.

The attackers know that simple economics is on their side as it is generally much less expensive to pay the ransom than to hold out. When hackers took down Baltimore’s computer networks last summer, they demanded a modest $76,000 in ransom. The city held out and has ended up paying over $5 million to rebuild the networks piece by piece and may have lost an additional $18 million in revenue.

So popular has this new form of cyber extortion become that it is now known as Big Game Hunting. This is part of a new network of sellers of specific tools on the dark web and buyers who respond to advertisements in the expectation of making a huge return for an investment that is often no more than $1,000. Some hacking kits are rented from the maker for a monthly fee, which generally includes updates to the kits that take account of the latest defenses.

When ransomware first appeared in 2013, it was quite unsophisticated and relied on the broadcast to thousands of computer users via a malware email that could lock up an individual computer. Paying a modest ransom of perhaps $100 could free up the personal network. Today, Big Game Hunting is much more common as a single point of entry into a large network can be easy to achieve and much more rewarding.

One of the most popular methods of access is via email including a Word document attachment. If the document is opened, malware is imported into the network that is specifically designed to map a system, find the weak points and then on command shut down dozens, perhaps hundreds of computers.

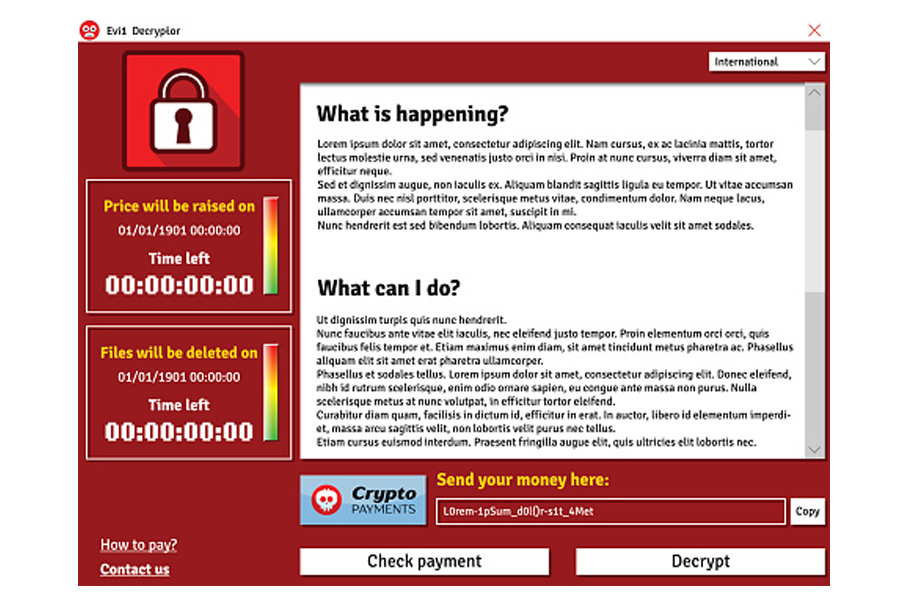

Alternatively, the hacker kit can encrypt all the data running on the network. Either way, a network will only be restored after a payment that can run into the millions of dollars, is paid in Bitcoin into an anonymous account overseas.

Exactly who is behind the creation of ransomware toolkits or who carries out a specific attack is cloaked in dark web mystery. Both toolkit makers and attackers hide behind layers of misdirection and secrecy as well as a bunch of cartoonish codenames such as Helix Kitten and Mummy Spider. But most roads lead back to nation states which are using ransomware to generate needed revenue or to test tools that might be used in a broader conflict where cyber attacks will be the opening salvos in a war.

The list of nation state suspects includes Russia, Iran, China, North Korea, India and South Korea. The National Security Agency has picked up hard intelligence that Russia is planning a broad range of cyber attacks this year with a goal of disrupting the November presidential elections. There are fears, too, that both Iran and North Korea may join in depending on what relations with the US look like closer to the time.

The Department of Homeland Security has launched a nationwide program to secure voter registration databases which it fears may be the subject of ransomware attacks. Last year, Russia was detected probing voter databases and today the DHS considers them a high risk target, in part because states and cities have often failed to ensure their defenses are kept current to match the evolving threat.

But ransomware has now moved beyond the nation state and is part of a new criminal ecosystem similar to what emerged in the 1970s and 80s in response to a rash of kidnap and ransom incidents carried out by terrorist groups and criminals. Then, Lloyds of London and other insurance companies began issuing insurance to companies and individuals. The kidnappers and the insurers regularly used intermediaries to negotiate a ransom and ensure the safe return of a victim.

Today, there is a whole industry developing to protect against ransomware that consists of insurance companies, cyber defense organizations and negotiators who handle the ransom payments and the safe rebooting of a network. In the US alone, the cybercrime insurance business is now worth around $8 billion a year with the insurance companies focused not on catching the criminals but on getting their clients back in business as fast as possible which often involves simply paying the ransom.

Exactly how much money was made last year from ransomware is unknown: many victims choose to keep quiet that they have paid a ransom in part because of the potential impact on the share price, and in part because of simple embarrassment. But experts are certain ransoms totaled in the tens of millions of dollars and of a significant increase on 2018.

Like any new weapon – and ransomware is a weapon of cyber war – it is easy to track the escalation to new and better weapons from a much simpler world. Twenty-five years ago, spam attacks to steal and sell data were the preferred weapon of choice. This was followed by basic blackmail, for example by an email that would claim that the recipient had been videoed using his own computer camera watching pornography. Failure to pay the $100 would result in the release of the video.

As the online world has exploded so has the nature of crime. For example, a recent scam involves several dating apps where a man might connect with an attractive woman who he then learns in an irate call from the girl’s furious ‘father’ that she is, in fact, underage and he is a child molester. Unless cash is paid for silence and the trauma caused to the girl, the conversation will be reported to the police. This scam was being run inside the US prison system.

Recent history shows that crime follows the path of cheap hacking tools that provide access to easy money. This means that ransomware is here to stay and will be a growth business for years to come.