It happened by accident. In 1829 the naturalist Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward was trying to hatch a moth pupa. He placed it in a sealed glass container, along with some soil and dried leaves, and set it aside. Sometime later he was surprised to find that a fern and some grass had taken root in the soil, despite having no water. As Sathnam Sanghera writes in Empireworld, the discovery “revolutionized the logistics of international plant transportation.” Suddenly there was a means of securely transporting seeds and seedlings across vast distances.

Empireworld is a sequel to Sanghera’s wildly successful Empireland. Where the latter examined the legacies of empire in Britain, this book seeks to apply that template to the world. What, then, do glass containers have to tell us about global imperialism? One result of Ward’s discovery was that Britain was able to transplant the cinchona tree, native to South America, to its colonies worldwide. Cinchona bark contains quinine, an alkaloid which prevents malarial fever; and it was quinine, together with the steamship and the Maxim gun, Sanghera writes, that enabled the late nineteenth century conquest of Africa by European powers. Before that, much of the continent was simply too deadly. A European arriving in Mali had a life expectancy of four months.

Sanghera finds British imperialists to be the fons et origo of all today’s unrest in Kashmir, Iraq and Myanmar

But the new global live-plant trade also spread pestilence: some 90 percent of invertebrate pests in Britain today arrived that way. Imported diseases ravaged imperial plantings; one fungus alone destroyed $2.5 million’s worth of coffee plants in Ceylon in 1869. Ward’s discovery then, was both a triumph and a disaster. As such it is a useful metaphor for Sanghera’s central argument, which is that trying to balance out the impacts of British imperialism by weighing “good” against “bad” is futile. It was both. In Empireworld he attempts a more subtle reckoning, traveling to former imperial territories such as Barbados, Nigeria and Mauritius, as well as examining issues such as humanitarian aid and the rule of law.

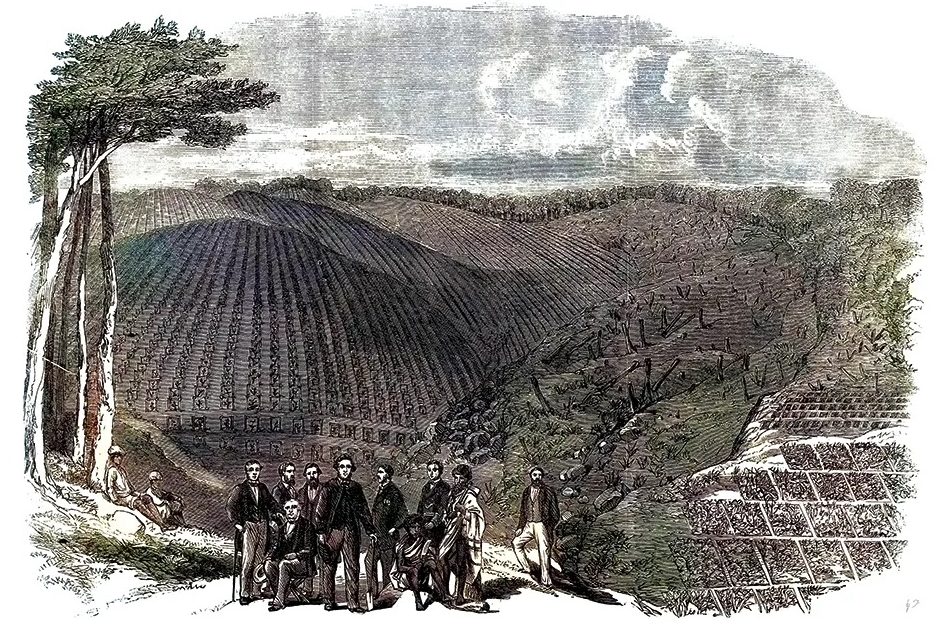

In places, Sanghera writes with power and eloquence. One chapter, “The Color Line,” is recommended for anyone who doubts that racism played a part in British imperialism. Also thoughtful are chapters on “economic botany,” touched on above, which saw Britain transplant flora, such as rubber trees and tea plants, across the empire to exploit them commercially — with devastating environmental and economic consequences — and on Mauritius, which discusses the issue of indentured labor.

Sanghera’s travels are a mixed bag, however. Exploring ideas of legacy involves an assessment of the present, and it is a shame he didn’t interview more experts on the ground — politicians, historians and academics — for more nuanced local perspectives. In his discussion of Nigeria, reliance on a limited range of sources results in imperialism being held responsible for everything from kidnapping and corruption to distrust of the nation’s law enforcement agencies.

He is also disinclined to engage with arguments that accord agency to peoples post-independence, writing: “If even half the things which academics identify as imperial legacies are direct imperial legacies… that’s a startling quantity.” This is perilously close to the “balance-sheet” history he otherwise deprecates, and it assumes historians’ conclusions to be more definitive than they are. Perhaps the concept of “legacy” itself, which both begs for an evaluative reckoning and demands a precisely measurable chain of cause and effect, is part of the problem.

Sanghera’s discussion of the rule of law, meanwhile, surprisingly sidesteps the large, systemic legacy issues, not least the role of the so-called Anglo-Saxon legal systems in maintaining the structures of global capitalism, in favor of a focus on homophobic legislation and historic injustices during the Raj.

Ultimately, Sanghera concludes that the British Empire “resists simplistic explanations” and should be seen primarily as “an incredibly complex mass of contradictions.” If the book’s arc is towards complexity, however, it still sweeps up too many simplistic judgments along the way. It takes just one paragraph, for instance, to make British imperialists the fons et origo of all today’s instability and violence in Kashmir, Iraq and Myanmar.

Reflecting on some of the conflicting legacies he has identified, Sanghera writes that it is “better to simply accept slavery/anti-slavery, destruction/preservation of animals/nature as phenomena in their own right and attempt to understand their complicated stories.” This is an important insight which — not least because it seems at odds with the premise of the book — merited further exploration. Empireworld is in part a plea for constructive dialogue about the Empire’s continuing influence on the lives of people both here and abroad. Reframing that as an exploration of historical phenomena in which the empire is merely one participant seems a different conversation entirely.

Overall, the book is too piecemeal to function as a history of empire. It works best as a lively narrative of Sanghera’s ongoing encounters with imperial history’s messily irreducible complexities. I hope he continues his journey.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply