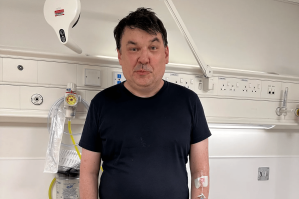

This week sees the official launch of the Free Speech Union — an organization that stands up for the speech rights of its members. It’s my baby, but a number of people have come on board as directors, including Douglas Murray and Professor Nigel Biggar. I’ve also had a lot of help behind the scenes from people who got in touch after reading about it in this column. I was on BBC Radio 4’s Today program on Monday to talk about it and have done a number of interviews since. By the time you read this, I’ll be recovering from the launch party, scheduled for Wednesday night.

So far, it’s going pretty well. About 1,500 people have contacted me wanting to join since I first started talking about it in August and I’ve managed to persuade some fantastic people to be on the various advisory councils, including Sir Patrick Garland, a former High Court judge; the historians David Starkey and Andrew Roberts; the satirist Andrew Doyle; The Spectator’s columnist Lionel Shriver; a number of journalists-cum-intellectuals, such as Claire Fox, Matt Ridley and David Goodhart; and 17 academics, including a professor of history at Harvard, the behavioral geneticist Robert Plomin and the feminist historian Zoe Strimpel. Now that the website is live, people are signing up at the rate of one every five minutes.

There’s been some push-back, of course. There was a puerile attack in the Guardian in which a columnist pointed out that our name for the basic level of protection extended to all members — ‘Sword and Shield’ — was suspiciously similar to a far-right German festival called ‘Shield and Sword’. As ‘guilt by association’ goes, that’s almost as feeble as the attack launched on Yorkshire Tea earlier this week because Rishi Sunak, the new chancellor, posed next to a sack of its teabags. After an army of left-wing trolls called for a boycott, the manufacturers had to issue a statement making clear it had nothing to do with the photograph and hadn’t been told in advance of Sunak’s plans.

The discussion on the Today program was more elevated, thank God. The presenter Justin Webb set out the standard rationale for restricting free speech: for too long, the voices of straight white men have been allowed to drown out those of marginalized groups and by reining in people like me you’re actually making it easier for others to participate in the public conversation. In other words, the people who insist on ‘safe spaces’ and ‘trigger warnings’ aren’t opposed to free speech; they’re just helping to create a level playing field in which everyone feels able to speak.

In response, I quoted Ira Glasser, the legendary former head of the American Civil Liberties Union, who said in a recent interview that it’s a mistake to think the historical beneficiaries of free speech have been bigots and patriarchs. On the contrary, without the protection of the First Amendment, civil rights leaders wouldn’t have been able to organize protest marches in the 1960s. Defending free speech is in everyone’s political interest, he pointed out, and the left would do well to remember that.

A better line of attack is that it’s hard to protect people being mobbed on social media, something we’re hoping to do, without appearing to be against free speech. After all, when thousands of Twitter users join a pile-on against someone accused of saying something offensive — which happened to Roger Scruton last year — aren’t they just exercising their speech rights? OK, in Roger’s case his words were taken out of context and deliberately twisted to cast him in a bad light. But what if the person in question genuinely does possess toxic views? Would the Free Speech Union come to their defense? If the answer’s ‘no’, the next question is: well, where do you draw the line? The temptation is to say, ‘Provided they stay within the law, we’ll defend them’, but that feels like a cop-out. In some cases, what looks like a dog-pile will just be an example of vigorous democratic debate.

Clearly, when it comes to defending people from being harassed or worse by the public authorities for exercising their legal right to free speech, we’ll go to bat for them. But if our members are attacked in the media — social or mainstream — we’ll have to use our judgment. One thing I know: if someone is the victim of a witch hunt, we’ll try to make sure they’re given a chance to defend themselves and not just presumed to be guilty and tossed to the wolves.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.