Over the coming weeks, a battle between Washington and Beijing over the inclusion of Taiwan as an observer at the World Health Organization will rage, reflecting the struggle between the People’s Republic of China and the United States over control over international institutions. Yet it also reveals the reality of the new cold war between the two countries, and the shift in focus of attention to ground-level tactics at the expense of grand strategies.

Long forgotten in the shadow of China’s rise and the intensification of both contact and competition between the PRC and the United States has been the island nation of Taiwan. As part of the price of normalizing diplomatic relations between Washington and Beijing, the CCP demanded that the United States de-recognize the Nationalist regime on Taiwan as both the formal government of mainland China and as an independent nation-state. The Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek also did not want to be recognized as a formal country, as that would mean the surrender of their hope to retake the mainland.

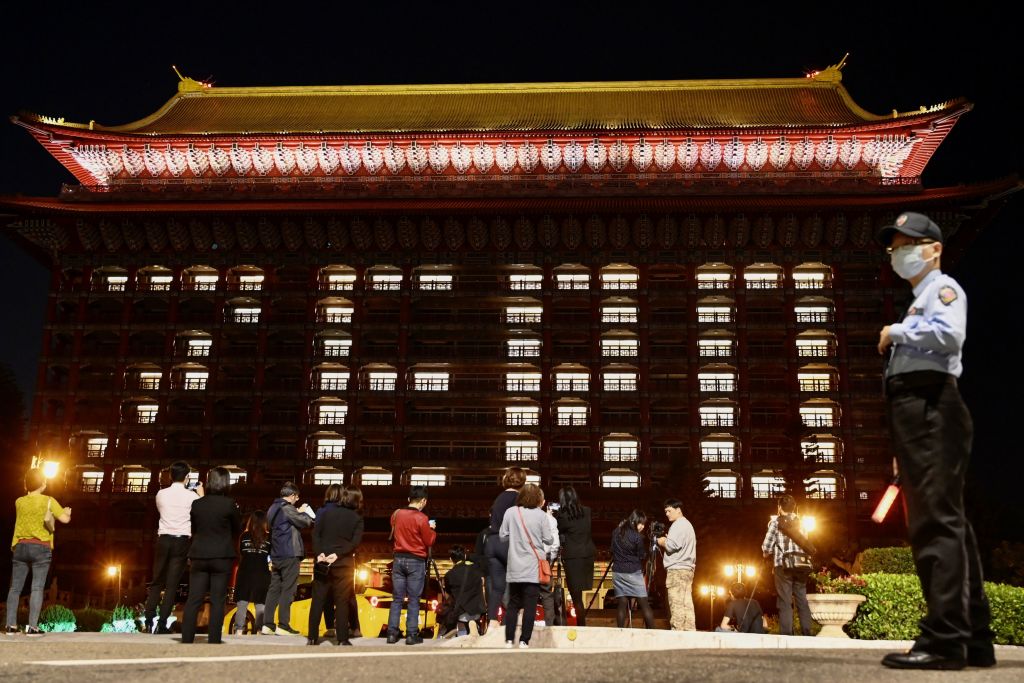

For four decades, Taiwan has undergone dramatic development and faced significant challenges. From a one-party autocracy, it embraced a robust free and pluralistic political system in the late 1980s, under Chiang Kai-shek’s son, Chiang Ching-kuo, to become one of the freest democracies in the Indo-Pacific. It also became a technological powerhouse, as the world’s leader in manufacturing semiconductor chips and home of companies producing advanced consumer electronics.

At the same time, Taiwan lived in an international limbo, having lost the vast majority of its diplomatic partners and being a non-entity in international law and institutions. As the PRC gained power and influence, it steadily chipped away at what international presence Taiwan did have, aiming at completely isolating the country from global political networks. Simultaneously, cross-strait economic ties between the mainland and the island grew after the election of Ma Ying-jeou as president in 2008, threatening to engulf Taiwan’s economic independence in the face of China’s dramatic growth.

While support for Taiwan has remained strong in the US Congress, it has fared less well with US presidents intent on enhancing ties with Beijing. The Trump administration has moved farther than most in enhancing ties with Taipei and working to increase Taiwan’s international space, aided by congressional initiatives that call for increased diplomatic interaction and encouraging other nations to work with Taiwan.

In the shadow of the coronacrisis that began in Wuhan, China, Taiwan has drawn international praise both for its successful policies to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, as well as for its attempts back in January to warn the World Health Organization that COVID-19 might be passed between humans. Since Beijing had falsely assured the WHO, and by extension the world, that such human-to-human transmission was not happening, governments across the globe considered the epidemic in China as far less dangerous than it really was, and found themselves unprepared for the onslaught that was unleashed by travelers from China around the world. The result was the greatest global crisis since World War Two and the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression.

Taiwan, however, is not a member of the WHO, and the organization, heavily influenced by China, ignored Taipei’s warning. Taiwan is not even accorded observer status, which it held from 2009 to 2016, during a period of closer Beijing-Taipei ties. Similarly, Taiwan has been blocked by the PRC from other international organizations, including the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), with such organizations refusing to share information with Taiwan or include it in any coordination, discussions, or planning.

Over the past decade, the number of Chinese heading up or holding senior positions in international organizations has dramatically increased, with the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission listing over two dozen such global groups, many sponsored by the United Nations. The fact that the general secretaries of both the ICAO and ITU are Chinese, combined with the close relations of WHO head Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to China, has led to suspicion that Beijing is using its position in or influence over international organizations to subvert their global mission and pursue policies that are in China’s interest.

Now the Trump administration is fighting to get Taiwan readmitted as an observer at the WHO, particularly for meetings occurring this month, placing the White House in direct diplomatic conflict with Beijing. Yet this is not the first time that the Trump administration has sought to check Chinese moves in international organizations. Earlier this year, Washington successfully backed a Singaporean candidate over the Chinese pick to head the UN’s World Intellectual Property Organization, a rare defeat for Beijing.

Whether Taiwan is accepted as an observer member of the WHO or not, Washington’s campaign on its behalf reflects the emergence of a new US approach towards the PRC. Instead of lofty grand strategies designed to reshape global governance or influence China’s internal development, the Trump administration is focusing on tactical-level operations, fighting for each meter of territory and, as in the case of Taiwan and the WHO, engaging in diplomatic combat with Beijing.

The new policy is a recognition that America’s grand strategy towards China did not turn out as expected, with a powerful challenger for global leadership emerging instead of a cooperative partner, and a Communist party-state antagonistic to US and liberal global norms. The days of grandiloquent statement of common strategic interest between Beijing and Washington are over, battered by trade wars, intellectual property theft, the growth of the Chinese military, and most recently by the Wuhan coronavirus.

In their place is emerging a steady, grinding campaign to make up lost ground and attempt to protect the ethos of responsible global governance while protecting American and allied national interests.

For countries like Taiwan, that is good news. Its long global limbo may partly be ended as a focus on uniting democratic countries in the face of Beijing’s challenge becomes the operating approach of the United States.

Michael Auslin is a fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and the author of Asia’s New Geopolitics.