American politics is getting senile. Donald Trump and Barack Obama were both elected as agents of change, repudiations of an ancien régime represented by the Bush and Clinton dynasties. But after eight years of Obama, Hillary Clinton inherited the Democratic party anyway. Frustrated with just how little had changed, voters clutched for a more radical alternative in 2016 — and they found it in Trump.

Now, if polls and betting markets are to be believed, the country is on the verge of turning its back on Trump. But if he does lose in November, his defeat does not promise to be a source of renewal — not when the alternative is a 77-year-old former vice president. The domestic and foreign-policy failures that created the demand for candidates like Obama and Trump in the first place have not been solved. The war in Afghanistan drags on toward its 20th year; the economy continues to concentrate wealth in the hands of a self-dealing elite; and the left and right alike feel culturally oppressed by the other side. Biden is not the man to deliver a new grand strategy or a new dispensation in economics or culture. Given his age, a Biden administration can only be a stopgap before another attempt at something new in 2024.

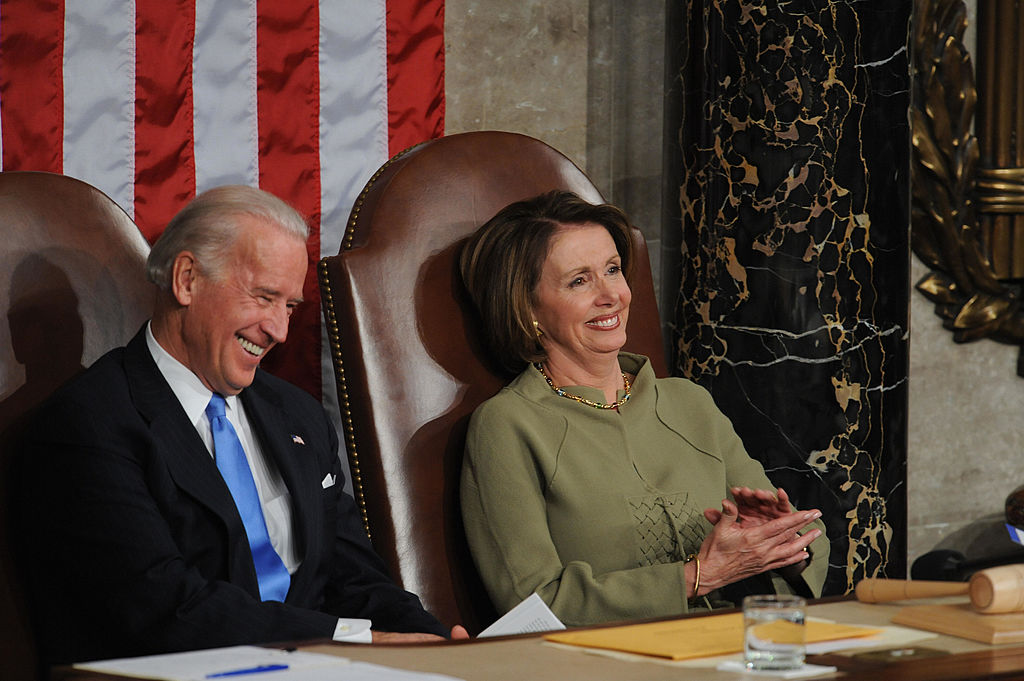

The Democrats are a party exhausted. Never mind Biden, just consider the party’s House leadership, which consists of the chamber’s oldest ever Speaker (80-year-old Nancy Pelosi), an even older House majority leader (Steny Hoyer, 81) and a third octogenarian as majority whip (James Clyburn, 80). The Republicans have a younger House leadership, but in the Senate, where they actually enjoy a majority, their leader is the 78-year-old Mitch McConnell. President Trump, at 74, is a cherub by comparison. If he wins a second term, he will leave office in 2025 as old as Biden will be at the end of 2020.

Yet politics is less bedeviled by the age of the parties’ leaders than by the staleness of the parties’ programs. Even the youthful Obama contributed nothing new to his party’s bank of ideas. He was all image — the substance of his administration was Mitt Romney’s Massachusetts healthcare plan and George W. Bush’s second-term foreign policy. Trump, by contrast, may have been old but he was the sharpest imaginable break with the past. Pat Buchanan and Ross Perot talked about economic nationalism, America First foreign policy and immigration in the 1990s. But now, with Trump, the populist program has for the first time been put into action.

Except, in important ways, it hasn’t. Trump and the populism he championed have been married these four years to the discredited and downright decrepit brand of the Republican party, a brand identity that lost the 2018 midterms and that hampers Trump’s message as he fights for re-election. Consider a parallel. Populism’s victories in America and Britain in 2016 were both victories against conservative parties. The actual Conservative party in the UK was then still led by David Cameron, an opponent of Brexit. His post-referendum successor, Theresa May, was also anti-Brexit, and predictably enough proceeded to make a pig’s breakfast out of leaving the European Union. Yet another leadership change was needed before the Conservatives finally had a leader, in Boris Johnson, willing and able to see the job through.

The election of Donald Trump likewise had to be accomplished in the teeth of opposition from a conservative party: the Republican party of the Bushes, Mitt Romney and the assortment of true believers who vied with Trump for the 2016 nomination. Populism prevailed but, as with Brexit, the old guard was unwilling to implement a new agenda. As May was to Brexit, so the Republican majorities in the House and Senate were to Trump. Rather than helping the President devise an effective populist program, Republican leaders in Congress insisted on such traditional priorities as defunding Obamacare and delivering a massive tax cut. Even within the executive branch, the conventional Republicans staffing the Trump administration continued to think in the accustomed terms of the George W. Bush administration — particularly where foreign policy was concerned.

[special_offer]

Trump is a populist president without a populist party. As bad as this is for Trump, it’s worse for the GOP. The party’s leaders and the conservative intelligentsia that advise them have known for decades that populism is the force Republicans must tap if they want to win: the force behind Nixon’s Silent Majority and the Reagan-era moral majority (not just Jerry Falwell’s group by that name); the force behind the Gingrich revolution of 1994, the Tea Party of the Obama years and finally Trump’s success in recovering states like Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin that had been lost to the GOP since the 1980s.

Yet the elites in the GOP and the conservative movement face two competing constituencies: the democratic constituency of voters, magazine readers, Fox News viewers and talk-radio listeners; and the oligarchic constituency of business-class donors and their own professional peers in the liberal-dominated mainstream media and academy. Populism serves the democratic constituency of the right, but it is anathema to the oligarchic constituency.

So which wins? The answer is the same as in the foreign-policy realm, where a democratic constituency of voters wants to win wars or avoid them, while an oligarchic constituency of experts, lobbyists and contractors wants to maximize involvement in all the world’s troubles. America is fundamentally an oligarchy and so, in the parties and in policy, the oligarchs’ preferences prevail. Trump, as rich as he may be, was a twist in the oligarchs’ expectations. But one man, even a president, cannot beat the system. Unfortunately for the oligarchs, though, the system can and will beat itself. If Joe Biden wins, he only postpones the inevitable and prolongs the pain.