Planning a foreign trip is a bit like watching a trailer for a film. The research is a preview of coming attractions. I almost never made it to San Antonio de Areco, a charming country town about seventy miles northwest of Buenos Aires, because it seemed extravagantly expensive and complicated to visit. But trailers can be misleading, perseverance is a virtue, and Areco, as the locals call it, turned out to be the highlight of my visit to Argentina last summer.

With just a week to spend in the world’s eighth largest country by land area, my plan was to spend four days in Buenos Aires and three in a small town, a place I hoped would give us an idea of what the country’s gaucho heartland is about. Areco seemed promising, but our visit — I was traveling with my wife and two teenage sons — coincided with school holidays in Argentina and the best-rated estancias (ranches) were either booked or prohibitively expensive.

Argentina is generally a bargain if you bring crisp, new $100 bills and exchange them locally. But rental cars were $150 a day, and when I first started looking for a place to stay, several establishments told me it was too early to quote a price as the currency fluctuates too rapidly. Here was an early lesson about our destination, where the official inflation rate last year was 94.8 percent. A month before we arrived, the black-market exchange rate was about 250 pesos to $1, compared to 140 for the official rate, which is what you get if you’re foolish enough to withdraw cash from an ATM or use a credit card. By the time we arrived, the informal rate was up to 320.

The establishment I chose, Hotel San Carlos, which turned out to be excellent, wanted me to wire them 58,595 pesos to make a reservation (credit cards are useless in Areco). When I balked, they said, “OK, just pay in cash when you come.” An Ecuadorian friend who had just visited Argentina solved our transportation problem by linking me up with Hernán, a Porteño (native of Buenos Aires) cab driver who offered to drive us to Areco for $50.

After four rainy, cool days in the capital, rays of sunshine and the fact that we all fit inside Hernán’s Nissan Sentra boosted our spirits as we motored off to Areco on a lovely midwinter morning. Areco is a popular getaway for affluent Porteños, but the place was eerily silent when we arrived at lunchtime on a Friday. Stray dogs slept in the middle of the streets, shops were shuttered for siesta and the gonging of church bells in the plaza emphasized the silence.

We celebrated our arrival at Lo de Fabiana, a food truck across from the hotel, with the first of many cheap, excellent meals. My wife and I had milanesas, the unofficial national sandwich of Argentina, which is a schnitzel-like treat that can be made with chicken or steak, while the boys had two-foot-long hot dogs. The bill for all that plus four orders of fries, two sodas and a large bottle of water came to the equivalent of $10.

More bargains followed. A relaxing, one-hour massage at the hotel’s spa set me back 2,200 pesos — just over $7. A haircut that my family said was quite bad, but I thought was very adequate, cost $2. An hour-long horseback ride with a guide at one of the estancias we couldn’t afford cost us $20, a bargain even accounting for the fact that my horse, Pancho, was probably the slowest steed in Argentina.

At Boliche de Bessonart, an atmospheric old bar full of antiques and gauchos with their characteristic big, floppy boina berets, mouthwatering empanadas cost the equivalent of 65 cents, while glasses of the local house vino cost 75 cents. At Café Tucano, on the town’s attractive main shopping street, Calle Alsina, I enjoyed a $3 bounty of farm-fresh scrambled eggs, homemade bread, jam, juice and good coffee twice.

No roundup of Areco bargains would be complete without mentioning the Copper Pot, a wonderful chocolate shop staffed by generous-with-their-samples teenage girls. I failed to record the prices at this place, but suffice it to say their chocolates were so addictive that we ate unhealthy quantities of them and couldn’t live within a 100-mile radius unless we aspired to star in a TLC show called My 3,000-Pound Family.

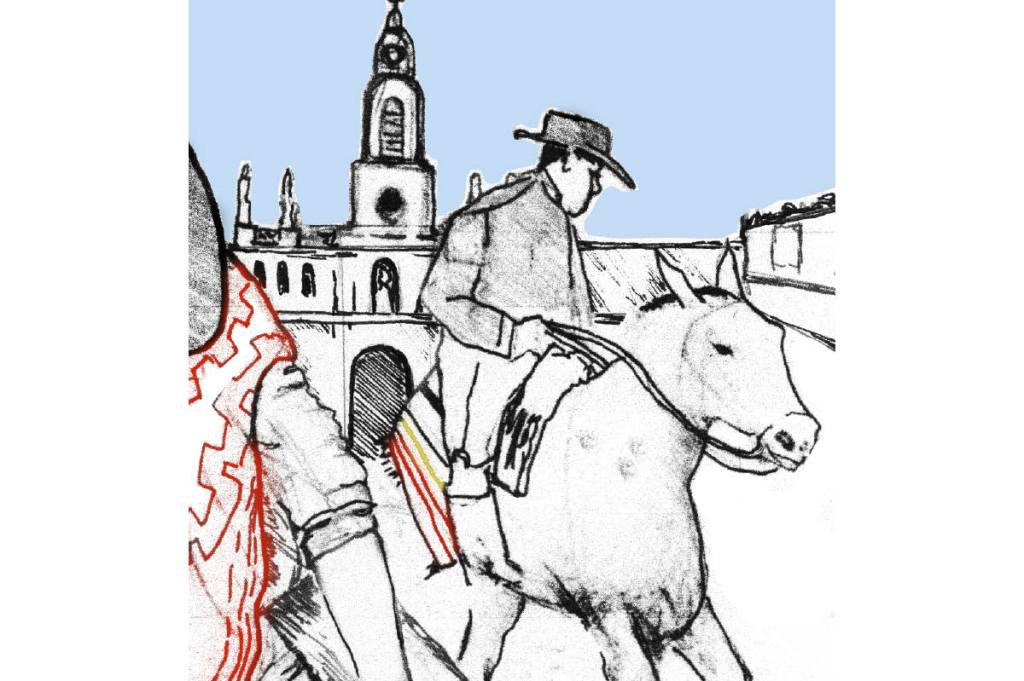

Areco is lively outside of siesta time. Perfect small towns must have an idyllic central plaza, and Areco does indeed, with lots of shade, a stately old church, neat rows of shops and restaurants and plenty of room for people, children and dogs to socialize. Gauchos occasionally ride through the streets on horseback, a tradition the town celebrates with gusto every year on November 9. The relaxed vibe gave us a chance to meet more Argentines than in busy Buenos Aires. After our horseback ride at Estancia la Cinacina, we chatted with a woman and her mother who were visiting from Buenos Aires. They moved to the US in 2010 and lived in Miami before decid- ing to move back to Argentina in 2017.

“It was a big mistake,” the daughter said of their decision to return. “All the young people are looking to get out of this country. Our politicians are crooks.” Her mother, a sprightly septuagenarian, thought “lazy people” shared the blame. “They all want to collect a check from the government,” she said. “No one wants to work.”

At our hotel, we made great friends over games of foosball with three generations of the delightful Kanelson family, who were also visiting from Buenos Aires. As my son, Leo, teamed up with eighty-year-old Leo against his granddaughters, Micaela and Melany, Patricia, their mom, told me why they keep coming back to Areco.

“The square, the church, the gauchos, it connects us to our culture,” she said. All that, she explained, plus they’re addicted to the Copper Pot’s alfajores, a kind of Argentine chipwich, but with dulce de leche sandwiched between the cookies.

My sons would rather eat hot coals, or better yet alfajores, than visit museums, but on Saturday afternoon, I dragged them to a museum devoted to the town’s most famous resident, the late novelist Ricardo Güiraldes. Güiraldes is the author of the 1926 novel Don Segundo Sombra, perhaps the best-known novel about gauchos. His mother, Dolores Goñi, was a descendant of Ruiz de Arellano, who founded Areco in 1730. The museum reflects Güiraldes’s tumultuous, peripatetic life and fascination with gauchos. After his first two books failed, he threw all his work in a well and vowed never to write again. His wife encouraged him to persist, and he did. With his gaucho novel, published when he was forty, he finally had a hit, but he died the following year after developing Hodgkin lymphoma.

Just as the faithful attend Mass on Sundays, so too do Argentines indulge in weekend barbecues, or asados. Asado is a religion in Argentina, and its adherents filled the outdoor tables alongside the Areco River at El Palomar, where the asadors grilled cuts of meat on crucifix-shaped stakes over open fire. We fell into conversation with a table of young women, daytrippers from Buenos Aires who recently graduated from university. Their gathering had a melancholy undertone: each was plotting how to leave the country; two wanted to move to Spain, one to Germany, one to Italy and another to the US.

“You can’t get a good job in this country unless you have the right connections,” one lamented. “But even if you do,” interjected another, “the salary is so low you can’t afford your own apartment.”

On our last day in town, a cheerful, curly-haired local guide named Veronica Gabriel showed us things we never would have noticed. For example, there’s a confessional in the pretty San Antonio de Padua church, which was specifically built for the Irish, who were once a sizable contingent in town. We were her first customers since before the start of the pandemic. “Tourists are just starting to come back,” she said.

Argentina had some of the longest lockdowns of any country. Veronica said that during the first, which lasted six months, almost no one left their homes, other than to buy groceries. Her husband’s pizzeria did gangbusters delivery business.

“People were so scared they didn’t even want to touch the pizza boxes,” she recalled. “So, the delivery people had to wear gloves and leave the pizzas outside.”

Veronica said that the government wanted to build a train line to the town from Buenos Aires but maintained most residents don’t want it. “We have our culture, our traditions here,” she said. “We like Areco the way it is.”

Our final stop with Veronica was an art gallery we hadn’t noticed before. She introduced us to the artist and proprietor, a mustachioed, boina-wearing gentleman named Miguelangel Gasparini. As we looked around, Señor Gasparini went back to work and Veronica told us that his father was the godchild of Don Segundo, the gaucho who inspired the character in Güiraldes’s novel. As we were about to leave, the artist called us over to his desk. “He has a gift for you,” Veronica said. Miguelangel presented us with a sketch he’d just made of us, riding on horseback through Areco. “Keep this,” he said, “it will remind you to come back to this place someday.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2023 World edition.