Draggle-tailed guttersnipe. Squashed cabbage leaf. Bilious pigeon. These are some of the insults hurled at Eliza Doolittle by Professor Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady. The musical is undergoing a Broadway revival this season, the first in 25 years, with Lincoln Center Theatre’s production directed by Bartlett Sher.

Sexual politics may be under the spotlight, in keeping with Lerner and Loewe’s original, yet it’s the British class system takes centre stage. Set in London, at the turn of the 20th century, My Fair Lady is the story of a flower-selling street urchin, Eliza Doolittle, as she becomes the willing subject of a social experiment conducted by ‘speech scientist’ Henry Higgins. It’s the tale of a self-made woman.

In Lerner’s words, the musical juxtaposes “the life she [Eliza] had as a Cockney” and the life she has “as a grand dame.” Eliza is effectively two roles in one — and comes with rather large shoes to fill.

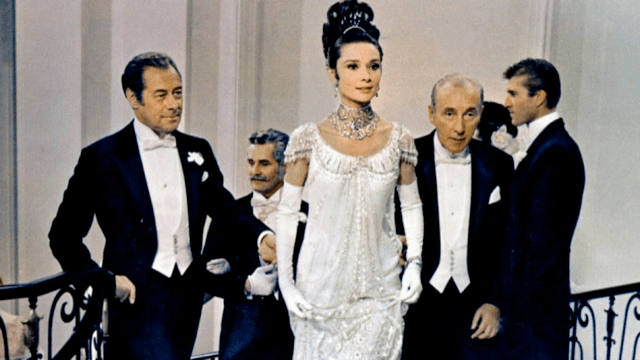

A 20-year-old Julie Andrews was the original star in the Broadway and West End productions in 1956 and ‘58. But not starry enough, it seems. When Hollywood made its film adaptation in 1964, Audrey Hepburn was considered the bigger name. Hepburn’s vocals didn’t quite cut it, though, so Marni Nixon ghost sang the part.

In Sher’s production, Lauren Ambrose makes a dauntless Eliza. Like Hepburn, Ambrose is a better actor than singer. But this does not detract. Quite the contrary, My Fair Lady is more’s Lerner’s than Loewe’s; more beloved for its text than its tunes.

It is based on George Bernard Shaw’s comedy, Pygmalion. Shaw’s socialism deemed that economic distinctions — including but not limited to class — were illegitimate. And so in Pygmalion, the new money of Eliza and her father ostensibly improve their fortunes but do not increase their happiness.

But when it first came to Broadway, the New York Times noted that Lerner and Loewe had added a “new dimension” to the work. And although “the Old Boy [Shaw] had a sense of humor, he never had so much abandon.” In this regard, it’s worth remembering that My Fair Lady was, essentially, an American invention intended for an American audience. Lerner explained that that, “we decided to leave it in 1912 because class distinction is not now as crucial a distinction as it was in those days.” Indeed by the 1950s the traditional British class systems, as well as gender roles, had been largely levelled by two world wars.

America, meanwhile, had always had a different attitude to social mobility. Under the Founding Fathers, capitalism was embraced. By the 1930s, the notion of the “American Dream” was popularised. The idea was that, in accordance with the Declaration of independence, equality of opportunity was on offer

to all. With the 19th amendment, in 1920, that included women.

In Sher’s production, as both a guttersnipe and grand dame, Ambrose’s feisty Eliza maintains impossible dignity. She turns up on Higgins’ doorstep, entirely of her own accord, to purchase speech lessons with the little money she’s earned. She has, you could say, an American-style self-starting attitude.

This is a stark contrast with her father, Mr. Doolittle, played by Norbert Leo Butz. Regrettably, Butz’s Doolittle is more irritating than funny. Though oppressed, in his own words, by “middle-class morality”, his performance lacks the usual redeeming charm. No doubt this is not as Shaw, nor Lerner, intended.

But in this production, it only enhances Eliza’s comparative strength. In the 1910s, a woman’s two choices were, if she was wealthy, to marry well; and if she was poor, to become cheap labour. But in Lerner and Loewe’s musical, and in Sher’s production, Eliza’s stalwart character, from the beginning to the end, is the show’s great triumph.

Ambrose, rightly, dominates the scenes with Harry Hadden-Paton’s slightly wishy-washy Higgins; and shows impressive argy-barginess in ‘Just You Wait Henry Higgins’. Throughout, their arguments are passionate, plausible, and entertaining. A nice contrast with her moments of elation, as in her spritely ‘I Could Have Danced All Night’.

Sher’s is a fairly traditional production in many respects: more revival than reinvention. Michael Yeargan’s stunning set establishes a familiar old London complete with lamp posts, townhouses, and stone pavings. Jordan Donica’s lovesick Freddy is appropriately wimpy and well-sung.

But leaving the theatre the story that sticks is of Eliza, the self-made woman. More significantly self-made, than woman: whose grit and determination lead to a change of fortune. The ending is as ambiguous as always — we suspect her struggle will continue. But is there a more American sentiment than that?