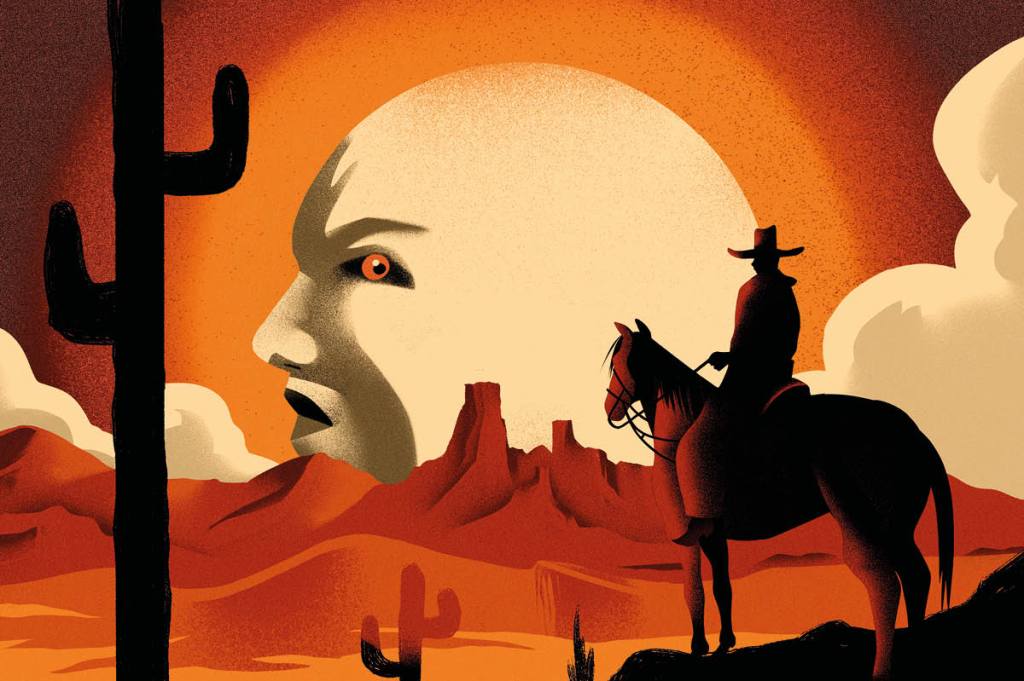

In June, Cormac McCarthy — our greatest living writer — slipped from this world to the next and joined his forebears Melville, Twain, Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor in the American literary pantheon.

By noon the following day, Blood Meridian, or The Evening Redness in the West, his magnum opus, had reached number eight on Amazon’s Top 100 Books, assuring that, for the first time, it would hit the New York Times Paperback Bestseller List; a curious development for a novel that, when it was first published in 1985, failed to sell its initial print run of 1,500 and was quickly remaindered.

But since its inauspicious debut, Blood Meridian has only grown in reputation and is now widely considered to be McCarthy’s masterpiece and one of the greatest novels of our era — quite possibly, the Great American Novel critics have searched for. It has sold steadily, if not swiftly, since the 1992 publication of All the Pretty Horses, the novel that made McCarthy famous.

Of course, that’s all changed now with McCarthy’s death and the renewed interest in his masterwork. The announcement in April that director John Hillcoat is adapting Blood Meridian for the screen (McCarthy had been said to be writing the screenplay himself) is also an encouraging sign, and if the film comes to fruition, Hillcoat’s two-hour book trailer will certainly drive sales even higher. It’s entirely plausible that we could see Blood Meridian occupying the top spot on both Amazon and the New York Times Bestseller List — a strange turn of fate for a strange and sublime novel.

But I wonder about all these people who will be getting Blood Meridian delivered to their front doors. What will first-time readers make of McCarthy’s blood-drenched novel? Having taught the book for over twenty years now, I believe I’m uniquely equipped to serve as guide for these would-be campaigners. Saddle up and take a tight grip on the reins: the road ahead is brutal and beautiful in equal measure.

In the late 1840s, a nameless teenager the narrator calls “the kid” runs away from his home in Tennessee. He travels to Texas and ends up in northern Mexico where he falls in with a gang of scalp hunters led by a former Texas Ranger named John Joel Glanton. Captain Glanton — and almost every other character in the novel — was a historical figure: we know about him chiefly from My Confession, a memoir by New Englander Samuel Chamberlain, who went AWOL from the US Army during the Mexican-American War and, like the kid, joined Glanton’s gang for a time.

Riding with Glanton’s gang (both in McCarthy’s novel and Chamberlain’s memoir) is a malevolent, Shakespearean character named Judge Holden. The Judge is a seven-foot-tall, hairless albino who speaks five languages; reads Greek and Latin; and is a draftsman, artist, amateur geologist, botanist and psychopathic serial killer. Holden acts as a kind of spiritual advisor to Glanton’s gang, lecturing the men on topics as wide-ranging as archaeology, mineralogy, theology, evolutionary theory and the philosophy of war. The Judge is one of the most fascinating characters in all of literature, and, as the critic Harold Bloom has noted, one of its most terrifying villains — in the tradition of Iago, Satan and Ahab. Of them all, Judge Holden is the most mesmerizing and memorable, and the most quintessentially American.

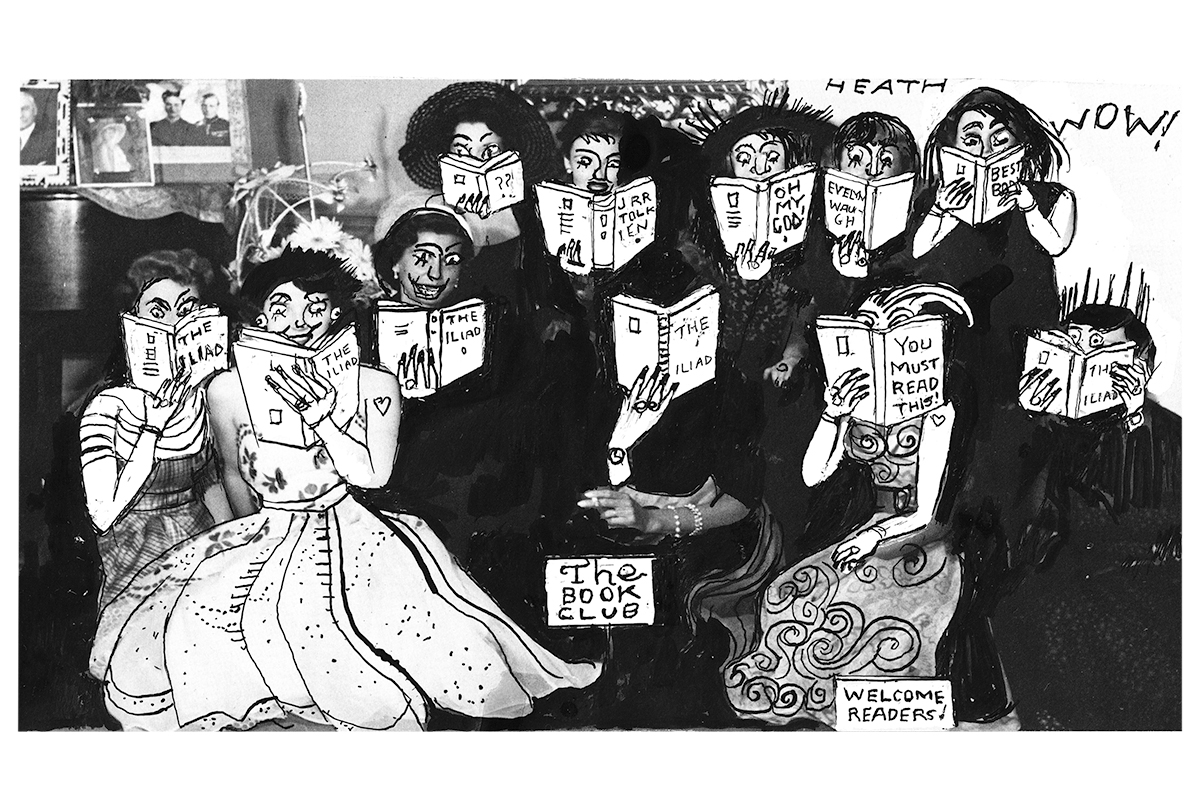

For most readers, Blood Meridian is a tough go. It is the most violent piece of media I’ve ever encountered. The Iliad, the Inferno, the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and the films of Peckinpah and Tarantino are tame by comparison. It is also written in some of the most sublime prose in the history of the English language, drawing heavily from its stylistic progenitor, the King James Bible. Turn to any page in the novel, pick any paragraph, any sentence, and you’ll encounter extraordinary beauty — a splendor of rhythm, cadence, detail and simile.

Take this Melvillian passage toward the end of the book where the kid looks for the first time at the Pacific Ocean:

He rose and turned toward the lights of the town. The tidepools bright as smelterpots among the dark rocks where the phosphorescent seacrabs clambered back. Passing through the salt grass he looked back. The horse had not moved. A ship’s light winked in the swells. The colt stood against the horse with its head down and the horse was watching, out there past men’s knowing, where the stars are drowning and whales ferry their vast souls through the black and seamless sea.

Or this, where the narrator directly addresses the reader in the manner of an Old Testament prophet:

Far out on the desert to the north dust- spouts rose wobbling and augered the earth and some said they’d heard of pilgrims borne aloft like dervishes in those mindless coils to be dropped broken and bleeding upon the desert again and there perhaps to watch the thing that had destroyed them lurch onward like some drunken djinn and resolve itself once more into the elements from which it sprang. Out of that whirlwind no voice spoke and the pilgrim lying in his broken bones may cry out and in his anguish he may rage, but rage at what? And if the dried and blackened shell of him is found among the sands by travelers to come yet who can discover the engine of his ruin?

Even the descriptions of atrocity rise to the level of epic poetry. Here, McCarthy describes a Comanche war party attacking a filibustering expedition that the kid has signed on to:

The company was now come to a halt and the first shots were fired and the gray riflesmoke rolled through the dust as the lancers breached their ranks. The kid’s horse sank beneath him with a long pneumatic sigh. He had already fired his rifle and now he sat on the ground and fum- bled with his shotpouch. A man near him sat with an arrow hanging out of his neck. He was bent slightly as if in prayer. The kid would have reached for the bloody hoop-iron point but then he saw that the man wore another arrow in his breast to the fletching and he was dead. Everywhere there were horses down and men scrambling and he saw a man who sat charging his rifle while blood ran from his ears and he saw men with their revolvers disassembled trying to fit the spare cylinders they carried and he saw men kneeling who tilted and clasped their shadows on the ground and he saw men lanced and caught up by the hair and scalped standing and he saw the horses of war trample down the fallen and a little whitefaced pony with one clouded eye leaned out of the murk and snapped at him like a dog and was gone.

In addition to being a brutal Western, beautifully told, Blood Meridian has a rich and interesting thematic depth, and offers sharp philosophical insight into the topics of westward expansion, Manifest Destiny, Anglo-American attitudes about Native Americans and race, and the very nature of warfare and human conflict. The book is deeply perceptive about the uses and abuses of violence, how nations — and many economic enterprises — are born out of blood.

Driving the ferocity of McCarthy’s novel is a troubling historical fact: in the mid-nineteenth century, the Mexican government was paying $100 in gold for every Apache scalp tendered to the authorities. The massacres perpetrated by Glanton and his men aren’t mindless — there’s a strong economic motive. Of course, Glanton’s gang soon learns that the Mexican government can’t tell the scalp of an Apache from that of any other Native person, nor can they distinguish the scalps of men from those of women and children. Eventually, Glanton and his fellow filibusters begin to slaughter almost everyone they come across, selling the “pelts” of Mexico’s own citizens back to its government.

The scalp is an important piece of currency, historically and symbolically. Very few people survived being scalped. Scalps were often referred to as “receipts”; these ghastly trophies were proof of another person’s death. It’s important to remember that, among members of Plains Tribes, removing a man’s scalp was a way of ensuring he could never enter the afterlife — to scalp a man was to destroy his soul.

At the center of this life-devouring, soul-destroying enterprise stands Judge Holden, seven feet tall and “bald as a stone,” brutal and brilliantly competent, as joyful in melée combat as he is fiddling at a dance, the Ultimate American practicing the ultimate American trade: warfare and war profiteering. For in the Judge’s philosophy, “all other trades are contained in that of war.”

Blood Meridian continues to provoke, unsettle and mesmerize readers not only for what it says about Americans in the nineteenth-century Southwest, but for what it says about America and Americans right now. It might not be the portrait of themselves that Americans want to read, but it’s certainly the portrait that we’ve earned.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2023 World edition.