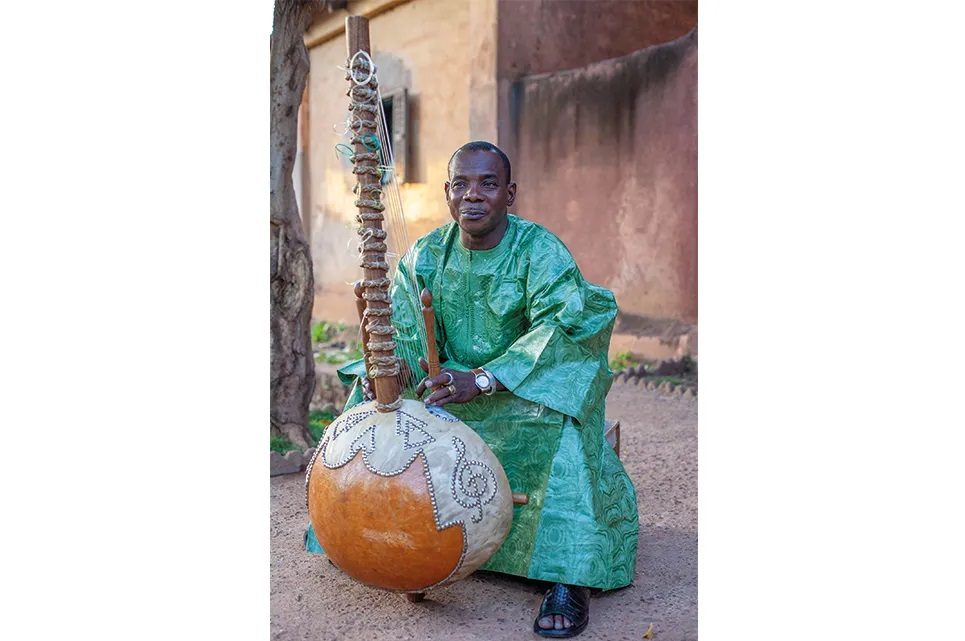

Early in 1987, a middle-aged woman approached me on the record counter of the Slough branch of Boots. ‘What do you have by Ladysmith Black Mambazo?’ she demanded. Nothing. Boots in Slough wasn’t big on South African isicathamiya choral music. ‘Well,’ she suggested, ‘you really ought to get their records in. They’re going to be huge.’ She was wrong, but I knew why she was so sure. Ladysmith Black Mambazo had been among the standout guests on Paul Simon’s Graceland, released a few months before.

Graceland made Simon, by my reckoning, the first pop star who had emerged from the rock’n’roll era to make a major cultural impact across three decades. By the 1980s, the Stones had become just a touring machine. McCartney was adrift. Doubtless someone will mention Bob Dylan, but no one was coming into the Slough branch of Boots in 1987 suggesting that we stock up on Peggi Blu’s Blu Blowin’ after hearing her work on Dylan’s Empire Burlesque. By contrast, Simon had been at the forefront of the 1960s folk revival (and its successor, folk-rock). He had crested the wave of the soft-rock singer-songwriter boom in the 1970s. And Graceland saw him way ahead of the game in incorporating African music into American pop.

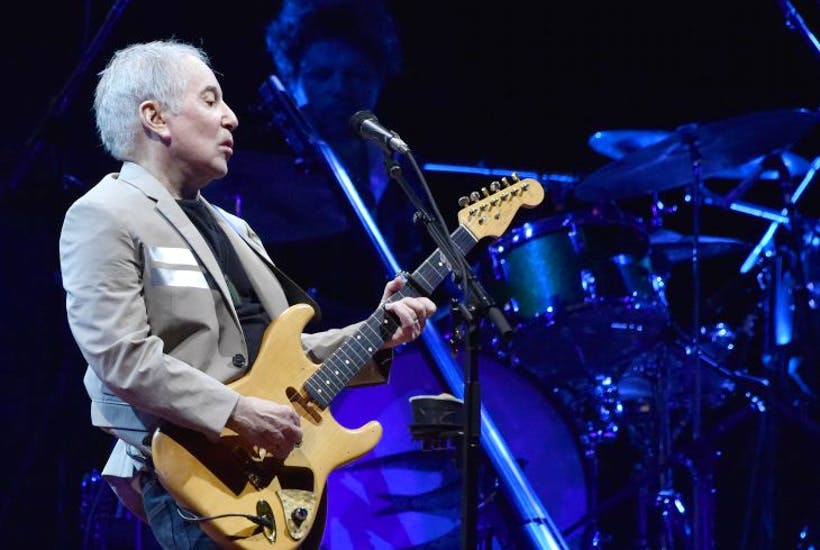

If the years since have been less commercially fulfilling — just five solo albums in the 32 years since Graceland, with a sixth to come in the autumn – they have not been a sad artistic stultification. Paul Simon has refused to sit still, a trait he brought to bear in Hyde Park at the last of this year’s British Summer Time faux-festival shows, billed as his final UK appearance. That said, his refusal to be predictable caused occasional problems when playing to 60,000 mildly pissed people outdoors, many of whom would have doubtless come for the usual reason people go to big outdoor shows: to hear the hits and sing along.

A section of chamber music arrangements was daring and inventive — ‘René And Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After the War’ is a gorgeous, strange song — but caused a certain restiveness in my section of the park. (Later on, during ‘Spirit Voices’, a woman to my left pulled out a bottle of nail polish and a file, and gave herself a manicure.) The first half played out in blistering sunshine that rendered the giant screens an irrelevance, and at a minimal volume that caused chants of ‘Louder! Louder!’ from the back of the field. Every song that prompted whoops (and there were plenty of them, from a gorgeous ‘America’ to open, to a limber ‘Me And Julio Down By The Schoolyard’ and the still foreboding ‘Boy In The Bubble’) was answered by others that needed rapt attention but were ruined by punters bearing pints of beer shouting out to work out where their friends were. At times, it felt like a brilliant show for an indoor venue that had been booked in entirely the wrong place.

But, gosh, the people who came to hear the hits got what they wanted in the end. ‘Diamonds On The Soles Of Her Shoes’, its a capella intro extended to highlight not just the African elements, but also Simon’s love of the doo-wop groups mentioned in ‘René And Georgette Magritte’, saw the first outbreaks of world-music dancing, that curious phenomenon in which middle-aged white people do a semi-limbo with their arms above their heads, something they never seem to do to music without an African element. During the encores ‘Graceland’ again proved itself to be one of the best pop songs ever written, a selection of lines so brilliant you can project any meaning you want on to it and never be dissatisfied, married to the most indelible of melodies from a man whose catalogue brims with indelible melodies.

Finally, Simon stood alone on the stage, his vast and brilliant band departed, for ‘American Tune’ and ‘The Sound of Silence’. No one was shouting out to find their friends or giving themselves a manicure. They were giving duly rapt attention to one of America’s greatest songwriters for the last time.