Since the 17th century, a ‘humourist’ has been a witty person, and especially someone skilled in literary comedy. In 1871, the Athenaeum said that Swift had been ‘an inimitable humourist’. But in modern usage the term seems to describe a specifically American job title: someone who specialises in writing short prose pieces whose only purpose is to be funny. The current king of humourists is David Sedaris, and his books are essentially scripts for his sell-out reading tours. But is he funny?

On a line-by-line basis, he sure can be. He helps push someone’s broken-down car, ‘and remembered after the first few yards what a complete pain in the ass it is to help someone in need’. He watches a reality TV show in which people write letters to their addicted loved ones: ‘The authors of the letters often cry, perhaps because what they’ve written is so poorly constructed.’ He comes over as rather like Larry David in Curb Your Enthusiasm, hilariously and inexhaustibly intolerant of the tiny outrages that other people constantly perpetrate.

Lots of pages also go by, though, without anything funny happening or being said. Being a collection of occasional magazine pieces, Calypso is quite repetitive, especially when it comes to what is really its main concern: houses. There is the house in West Sussex where Sedaris lives with his partner; there are other people’s houses, and there is, repeatedly, the beach house he buys in Carolina, and names ‘Sea Section’, where he hangs out with his father and siblings. ‘Another thing I love about the beach is sitting in the sun,’ he tells us, unnecessarily.

Perforce less funny is Sedaris’s account of his youngest sister’s death by suicide in 2013, and the description of his mother’s slide into alcoholism, which are flintily unsentimental passages. Indeed the publishers classify Calypso as ‘memoir’, which is an interesting hedge: when it came out a decade ago that Sedaris’s ‘non-fiction’ stories were embellished and partially invented, National Public Radio in America decided to classify them instead as fiction. Did he, as he recounts in this book, really have a benign lipoma excised from his body by a Mexican doctor he met at a show, and then feed the tumour to a turtle? Is he really the awful man he gleefully describes himself to be, compulsively telling grim lies to strangers for what is supposed to be comic effect? Perhaps, in the world of humour, it doesn’t really matter.

No such worries attend the stories in Hits and Misses (classified as ‘fiction’) by Simon Rich, who is also a comedy screenwriter. They are plainly fantastical squibs, either short stories or the kind of wry surrealism you get on the ‘Shouts & Murmurs’ page of the New Yorker, which is indeed where many of them started out. A writer discovers his unborn son is already composing the great American novel in the womb (starting with a pencil, and moving on to a hipster manual typewriter). A woman who was once in a band starts composing music again: aghast, her family and friends stage an intervention and send her to rehab for recovering artists. A writer (yes, another one) meets a succession of his past and future selves.

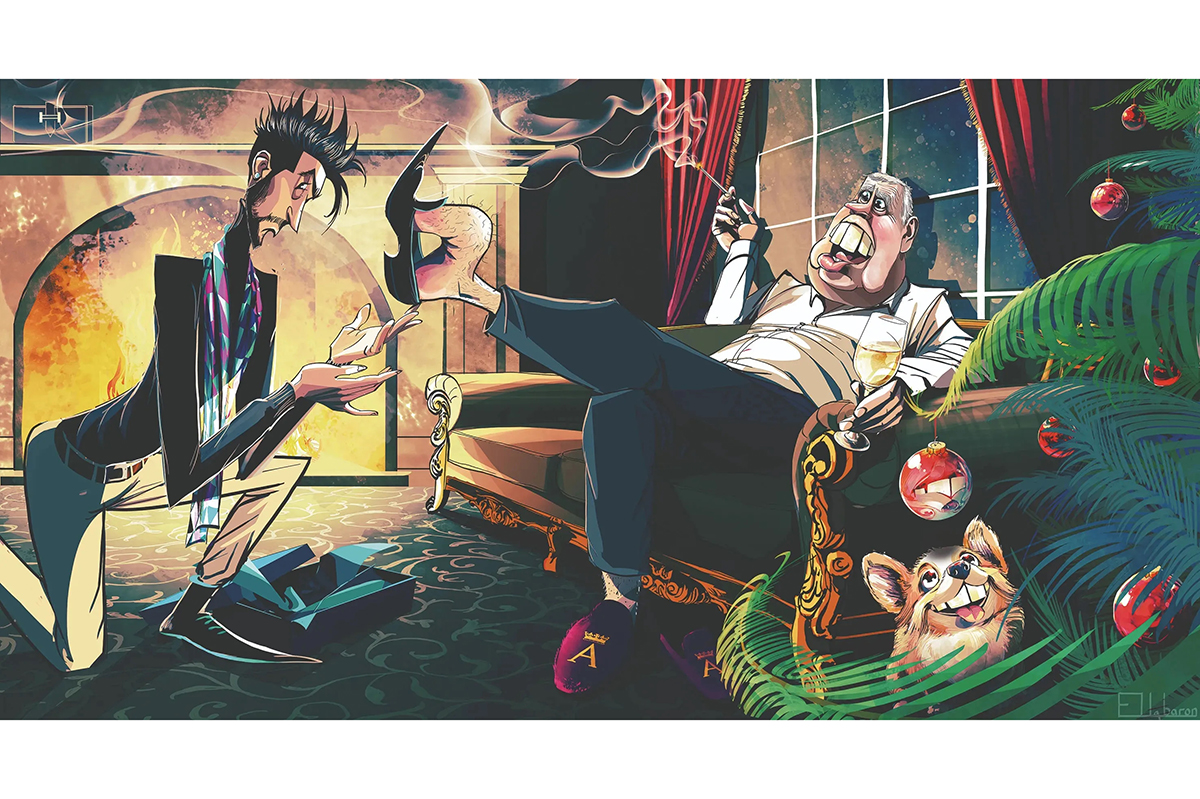

Rich likes deluded or unexpected characters. One story is narrated by a medieval jester, who recounts:

One question I am often asked is: ‘How did you become the royal jester?’ or ‘How is it possible that you’re the royal jester?’

Another piece is a faux-GQ magazine interview with Adolf Hitler, which is perhaps a mild parody on the ‘normalisation’ of Donald Trump by the American media. (Hitler likes French fries, and is studying Brazilian jiujitsu while working hard on his next genocide.)

The most obviously satirical piece turns on a shamelessly elaborated pun: an ageing comedy writer (again!) who is out of touch with what young people think is also, literally, a dinosaur. He cracks jokes about killing people with his mouth. This tends, the showrunner tells him regretfully, to make his colleagues feel ‘unsafe’ and ‘uncomfortable’. Now sacked, the dinosaur vows to get his own back against ‘political correctness’, like so many other middle-aged males who aren’t actually fearsome reptiles. Another story, meanwhile, is narrated by a horse, who does not use definite or indefinite articles. Is he supposed to be a Russian horse? Perhaps, in the world of humour, it doesn’t really matter.

Much of this is amusing and diverting, along with the inevitable damp squibs. In my favourite piece, a funny and touching miniature, a Hollywood agent manages to sign Death himself, who speaks in all capitals. So, I remembered, does Death in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels. Was he a humourist, or something more?