The year was 2007. The Bush administration was launching bombs in the Middle East, the economy was collapsing and pop songstress Britney Spears was standing in a recording booth at Sony’s New York City office. As Spears waited to lay down vocals, producers Ezekiel Lewis and Christian “Bloodshy” Karlsson discussed the latter’s condo in Bangkok, Thailand.

“Oh, Thailand,” Spears said, according to Lewis’s recollection. “Why don’t we go and do the songs in Thailand? Let’s go to Thailand. I have the plane coming tonight.”

Lewis looked across the studio at Karlsson and mouthed, “What the fuck? Is she serious?”

She was dead serious.

“Well, why don’t we get this one down first, and then maybe let’s think about it tomorrow?” he said.

They finished the track, then a funny thing happened. Spears turned to Lewis: “You got anything else?”

They didn’t, so Spears ventured to a back room to feed her baby sons, Jayden and Sean Preston Federline. In her absence, Bloodshy played Lewis some dubstep beats. Listening to them, Lewis recalls thinking, “It was gritty. It was dark. It was melancholy, yet it was dance somehow. It encompassed so many different human emotions. It was able to capture the mood of the time.” He picked up a pen and began writing lyrics the second they popped up in his mind: Make it a freak show… We can give them a–what’s the word? A peep show! A few minutes later, Spears returned, looked at Lewis’s lyrics, and sang into the mic. They wrote and completed “Freakshow” in ten minutes.

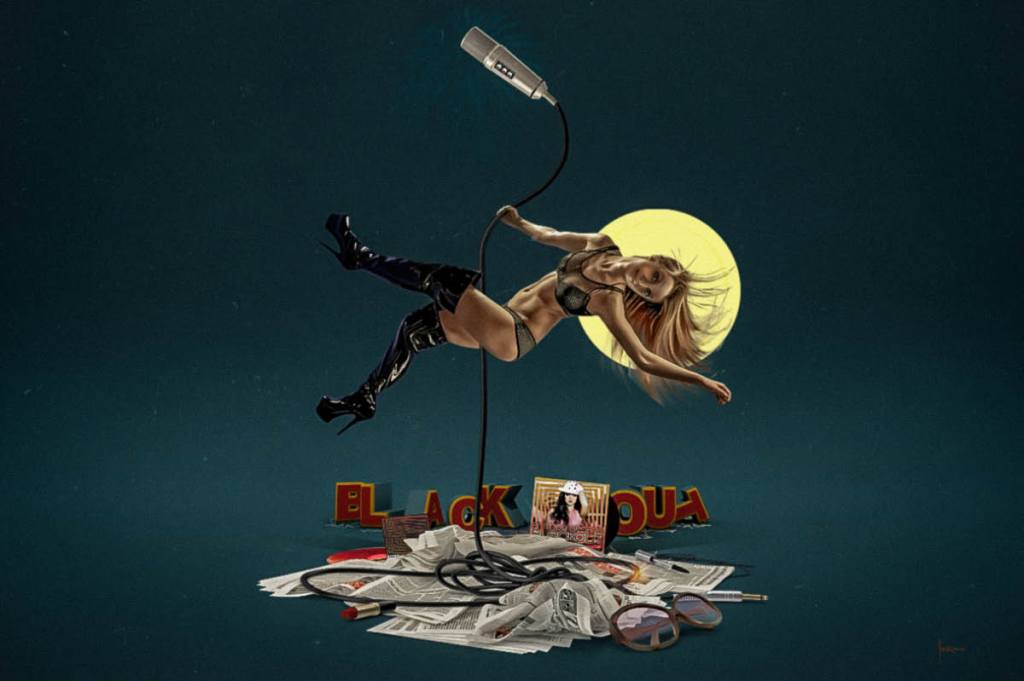

Those ten minutes would change pop history. “Freakshow” transported dubstep from London nightclubs to American pop radio, and it wasn’t even the most influential song on Spears’s 2007 album, Blackout. Recorded and released at the height of Spears’s public meltdown, Blackout mixed confessional lyrics, I don’t-give-a-fuck mantras (“It’s Britney, bitch,” “I’m crazy as a motherfucker / think I give a damn?”), EDM beats and experimental instrumentals into hit singles like “Gimme More” and “Piece of Me.” More importantly, it laid the foundation for the EDM revolution, Lady Gaga’s self-referential debut album, and the rest of the past fifteen years of pop.

It had a strange afterlife. Spears promoted Blackout via a disastrous lip-sync VMA performance of “Gimme More” and three low-end music videos. Although the viral VMA fiasco pumped “Gimme More” to number three on the charts, the album was Spears’s first album not to debut at number one. Yet over the past decade, it’s developed a cult following. There’s a reason music heads call it the “OK Computer of pop.”

Blackout is once again in the news because HBO’s new show The Idol revolves around a 2007-era Spears-like singer. “When was the last truly fucking nasty, nasty, bad pop girl?” actor Troye Sivan’s character asks in the trailer. Then “Gimme More” begins playing.

Following “Gimme More,” Spears’s personal dramas led to the court-ordered conservancy that allowed her father to control her life. But what made Blackout happen?

Blackout marked a departure from both Spears’s sound and her business team. She went on hiatus in 2004, and in the interim, she married Kevin Federline; wore a tracksuit to her wedding; filmed videos of herself partying, which she edited into the disastrous UPN reality show Chaotic; birthed a baby; got pregnant with another; and fired her longtime manager Larry Rudolph. She owed Jive another album, but nobody at the record label wanted a piece of her.

A new Jive A&R executive, Teresa LaBarbera Whites, did, though. Whites was one of the most successful music execs of her generation; she made her name discovering Jessica Simpson and signing Destiny’s Child, and she would go on to A&R Beyoncé’s Lemonade.

Whites doesn’t remember when she first met Spears — she explains that she measures time by songs, not years — but the singer was coming off her reality show and media coverage of her driving around the Hollywood Hills with a baby in her lap. Whites went to Spears’s mansion for a brief meeting. They didn’t discuss the headlines; music was on Spears’s mind.

“You’ve got to come with where you are now,” Whites recalls saying. “You’ve had a baby, and you’re a little bit older. So what does that sound like?”

To answer that question, they took an experimental approach. Instead of coming up with a creative brief, as execs typically do with pop albums, Whites and Spears assembled a suicide squad of unexpected partners. Blackout was them against the world.

Early producers and writers ranged from American Idol judge Kara DioGuardi to Eminem’s go-to-guy, Fredwreck. “[Her voice] has a texture,” he explains. “One thing about me as a producer, I really like working with people that have very distinctive voices. Snoop has a very distinctive voice. He’s not a very hard rapper, but he’s got a very smooth and distinctive texture — Britney has the same texture.”

“You always know it’s Britney,” says DioGuardi, who wrote “Oh Oh Baby.” “[She’s] sort of a throwback. It’s got a bit of a Broadway element to it. It’s a character voice, which has been adapted to the pop market… You have a brand of Britney. You can experiment. You can do a lot of things, and your fans are willing to follow along with you, as long as it’s still authentic.”

Whites was looking for a central producer, so she asked around LA. She kept hearing, “You got to try this guy [Danja] out. He’s like Tim’s secret weapon. He’s the guy in the closet making all [the beats].” Tim was Timbaland. Everyone from Nelly Furtado to Justin Timberlake to Björk to Madonna hired the producer in the mid-aughts. Whites wanted something different.

She met with Danja, and he played her beats. “His tracks were just fresh,” Whites said. She brought along Danja and his songwriting and production collaborators, including Jim Beanz and the Clutch: a collective that included Ezekiel “Zeke” Lewis and Keri Hilson. In that first meeting, Beanz remembers Whites telling him, “Definitely, be as crazy as we want. Try not to be too on the nose, or on the cuff, as far with her personal life, or anything like that.”

Returning from In the Zone were the “Toxic” masterminds, Christian “Bloodshy” Karlsson and Pontus “Avant” Winnberg. Whites’s sales pitch: make anything besides “Toxic.” “You’re never going to find another ‘Toxic,’” Whites says. “You are lucky you got the first ‘Toxic.’” Karlsson agreed. Karlsson wanted to work with Spears again because, unlike other pop girls, he says, “She was always giving me all the tools I needed to be free and do what I do best.” Spears didn’t want to create another “Toxic”; she wanted to experiment.

Whites’s one demand was that Spears work on the songs instead of having producers spoonfeed her material. “You should be a part of this,” Whites said. “You got something to say.”

“What did she have to say?” I asked Whites.

“Well, it’s in the songs.”

Recording commenced early on in Vegas, the same city where Spears would later headline one of the city’s most profitable residencies of all time. Ahead of the first session, Danja, Lewis, Beanz and Hilson were nervous. They were unsure how involved Spears would want to be. She arrived late in sweats, pregnant with her second son. While chewing on ice, she asked questions. “It took me by surprise how interactive she was,” Danja recalls. “How free she was.” Her ice-chewing made noise, Beanz noticed it, and penned a lyric for what would become the third single, “Break the Ice.”

Similar inspiration took hold whether the recording occurred in Vegas, LA or New York. The team would often create instrumentals before Spears arrived. In one studio, Danja played the bones of a song: the beat, bassline, tempo and drums — what he calls “the groove.” Hilson and Beanz layered on lyrics. Eventually, they had “Gimme More.”

Danja knew he’d have a brief period to play it for Spears,who tended to pop in for fifteen minutes at a time. Beanz recalls her assistant asking if Spears could use the bathroom. Then she vanished. It became a joke. “I don’t have to come in on cue,” Beanz said. “I’m Britney, bitch.” The control room laughed.

“Oh my gosh,” Beanz said. “I should tell her to say, ‘It’s Britney, bitch.’”

“No, don’t say that,” Danja said. The adult in the room, he worried Spears would flip out.

But when Spears climbed into the recording booth that day, Beanz said, “Excuse me, Brit, would you mind saying, ‘It’s Britney, bitch?’”

“It’s Britney, bitch,” she said. No questions asked.

Danja placed it as the lead for “Gimme More,” the opening track of Blackout. He was nervous about Whites’s reaction. When he played it, she said, “We’re keeping that in there. Hell yeah.”

Although Spears wrote little of the album, her taste dominated what she chose to record. She rejected some songs, but when Danja asked her to sing, “I’m crazy as a motherfucker, think I give a damn?” on “Get Naked,” she jumped at the opportunity.

“She was totally into [that line],” Whites said.

“She loved it,” Danja said. “I think she recognized it as something a little bit different than what she normally would do. It was hard-hitting and edgy and she could dance to it, and she was loving it… At this point, we were working with Britney, who has done a lot. She’s done numerous singles, numerous albums, numerous sales. It was perfect timing for her to come a completely different way, a little bit more raw, a little bit more edgy, which is the way music was headed anyway, and that’s the sound that we introduced.”

Near the end of recording, the media had overwhelmed Spears. Whites remembers seeing this firsthand one day when Spears was exiting Sony’s New York studio, holding her baby, into a swarm of cameramen. Whites was behind Spears at the door and watched her nearly fall to the pavement, baby in arm.

“It was like, ‘Oh, Britney almost dropped the baby,’” Whites said. “Well, the part they didn’t fucking write is that the motherfucking paparazzi bum-rushed her and hit her. Door opens and they just came from nowhere, like locusts and ants and just about knocking her down, and she just got back in the car. So cruel. So mean. And I watched it all unfold and I was so angry.”

Whites called Karlsson and Winnberg to pen an anthem about the press. The next time they were in the studio, Karlsson asked Spears to describe how she was feeling. “People usually don’t want to talk about those things,” Karlsson says. Instead of writing a sad ballad, Karlsson and Winnberg penned an aggressive, proud middle-finger to the press. They worked in the studio with their Swedish friend Robyn, whose album Body Talk would get Brooklyn hipsters dancing a few years later; they asked Robyn to sing backup vocals. Then they added a snare drum that sounded like a chain hitting the floor. Spears sang:

I’m Miss bad media karma Another day another drama Guess I can’t see no harm In working and being a mama And with a kid on my arm I’m still an exception And you want a piece of me

It would take years for the public to recognize Spears’s liberation. Danja recalls knowing it would take time for Blackout to take off, even back in 2007. The name even played off the idea. “This was after the turmoil, after some of the things started happening, and they had to turn this whole thing into something,” Danja says. Spears was tuning out the public noise, dancing on her own to the music she wanted to hear. As Danja says, “It was just like a lights-out type of aggressive thing.”

Some critics claim that Spears contributed few vocals to Blackout, citing the lack of studio time, but each producer disputes the argument. During production, background vocalists sang extensive vocals, but in mixing, producers brought her voice to the forefront. DioGuardi believes the album works because of the centrality of the voice: “You always know it’s Britney, and when a producer doesn’t accentuate that part of her tone to make sure you know it’s Britney, they’ve done her a disservice.”

Blackout would be the last time Spears would ever be artistically free. By the time she commenced work on its sequel, Circus, she was in a conservatorship and working with Larry Rudolph again. It was no longer possible for a pop star to go punk. Fifteen years later, in the words of The Idol, we’re still waiting for the next truly nasty pop girl.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.