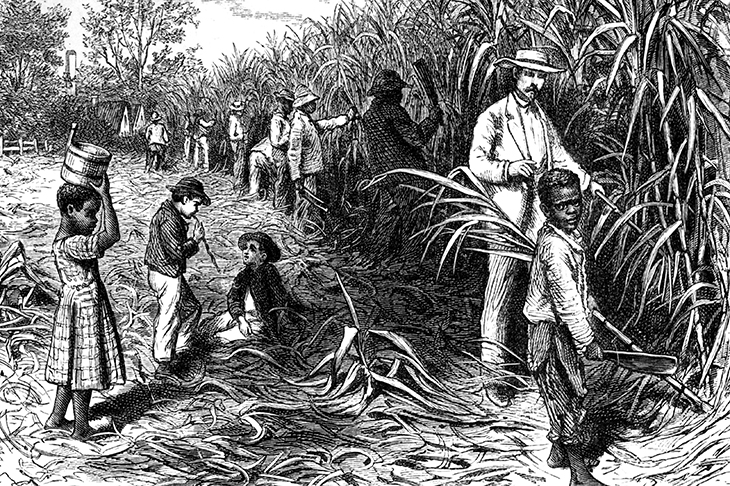

It’s 1830, and among the sugar cane of Faith Plantation in Barbados, suicide seems like the only way out. Decapitations and burnings are performed with languorous cruelty. Women give birth and are sent straight back to work after lying their ‘tender-skinned newborns down in the furrows to wail against the hot sun’. Esi Edugyan’s third novel does not retreat to softer ground after her last, Half-Blood Blues, dealt with Nazi ideology. Both Germany and Barbados have chapters in their histories when humans were treated like mere creatures.

Hope arrives with the plantation master’s brother, Christopher ‘Titch’ Wilde, a scientist, inventor and abolitionist. Titch chooses a slave boy, George Washington Black, to be his apprentice. Wash, as we come to know him, may be a ‘brute born for hard toil’, but he is singularly sensitive. The youth has a gift for observation, whether sketching the tentacles of a jellyfish or witnessing a mutilated corpse with its ‘explosion of teeth and bone, like bloated rice on the blood-slicked grass’. As Titch schools Wash in the ways of science, art and literature, affection and respect bloom between them.

The ‘Cloud-cutter’, Titch’s aerodynamic contraption, is finally ready for the pair to make their escape. But like a marginally more fortunate Daedalus and Icarus, they don’t stay airborne for long. A picaresque adventure ensues on storm-washed ships to Arctic igloos, through London squalor, to the desert hinterlands of Morocco. As Titch’s passions come to include the camera obscura, scenes take on a disorientating, almost magical quality which call out for an ambitious Hollywood director.

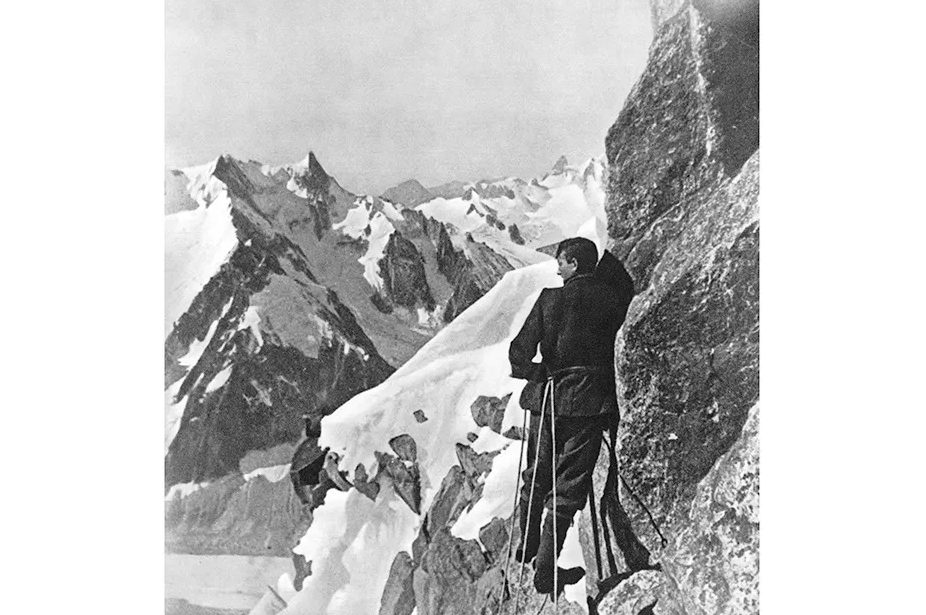

The novel is a pacey yet thoughtful exploration of freedom, and our moral compulsion to act. Titch embodies the shared imperative between abolitionism and science, ‘to doubt appearances and to seek substances in their stead’. As a side-project, Titch is in Barbados to report on the cruelty he witnesses on the plantation, but his scientific code of objectivity prevents him from intervening to stop the atrocities. And so Edugyan avoids the naive assumption that science is always a force for good. One Dr Quinn has ‘ready access to the slaves for his experiments’, to dabble in a ‘putrid fever’ vaccine. When we meet Titch’s father, he is so committed to remaining an observer that after a flying experiment fails, he pontificates on the theory of gases while the balloonist drowns.

Wash seeks freedom in captivity by setting up the world’s first aquarium, where ‘people could come to view these creatures they believed nightmarish, to understand these animals were in fact beautiful and nothing to fear’. And so the novel becomes a joyful celebration of another creature-liness, of our affinities with nature, from the German identical twins whose ship rescues Wash, to the two-headed cetacean which becomes one of his exhibited specimens.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.