Five years ago President Xi Jinping gave a speech in Kazakhstan, launching the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’, a wildly ambitious set of Chinese-backed infrastructure projects stretching through the steppes of central Asia to the Baltic Sea. Hundreds of billions of dollars later, this project more than any other has come to define China’s radical ambitions to upend a world order long dominated by Americans and Europeans.

In 2015, Peter Frankopan, a dashing Oxford academic, wrote The Silk Roads, a weighty and widely acclaimed history of the ancient trading routes that once linked China to the world. It became a bestseller, partly because Frankopan, unusually for an academic, knows how to tell a yarn. But it can’t have hurt that there were so many modern echoes in his bold historical retelling, in which Herat, Kashgar and Samarkand were cradles of civilization on a par with Byzantium or Rome.

This contemporary itch seems to have sat with Frankopan, prompting him to write The New Silk Roads, a slimmer ‘sibling’ volume detailing the flow of goods and ideas that are now sweeping once again from east to west, many of them along the same routes traversed in antiquity by Marco Polo. ‘The world’s past has been shaped by what happens along the silk roads,’ he writes. ‘So too will its future.’

Much of this is indeed about China, given that these new silk roads are typically planned by Chinese technocrats, funded by Chinese banks and built by Chinese workers. This, in turn, gives Frankopan’s new volume its narrative brio, as he zips back and forth across the Eurasian landmass, from new Chinese rail projects in Laos to oil pipelines in Iran.

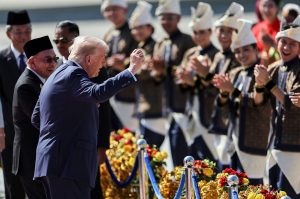

But this is a story about a more complex world too. The old powers of the West are in decline, accelerated by the missteps of Donald Trump, of whom Frankopan is no admirer. Into the vacuum step middling powers such as Turkey, Iran and India, ready to throw their weight around. Smaller nations in central and south-east Asia, long used to taking geopolitical dictation, are busily forging ties with one another. ‘That is what always happens along the silk roads, the networks that are the world’s central nervous system,’ Frankopan suggests.

This can be overplayed. China’s infrastructure largesse is indeed unprecedented, and also increasingly visible on the ground; a jaunty red and yellow freight train arrived in east London last year, having taken a 7,500 mile, 18-day journey overland from eastern China for the first time. Nonetheless, maritime trade remains much the most important conduit of global goods, while services zip around over the internet. The regions Frankopan describes as a central nervous system are in fact among the world’s least economically integrated and significant — a fact that won’t change quickly, no matter how much money China ploughs in. Even so, Frankopan’s is an entertaining and carefully researched account of a new Chinese chapter in global history, and one where it finally makes sense to see Eurasia, with Europe at one end and China at the other, as a single connected whole.

The book’s weakness is the thing you might not expect from an adventuring historian, namely its lack of a sense of the past. Slap bang up to date, The New Silk Roads manages to bring in events from just a few months ago, such as the election of Imran Khan as Pakistan’s prime minister. But it glances over the deeper historical forces shaping this new era of connectivity. This is a shame, not least because it’s a topic Frankopan is well placed to explore. ‘Talk of the silk roads of the past is helpful in providing a common narrative which binds people and cultures together,’ he writes at one point. Much the same would be true here in explaining China’s contemporary motivations, for instance, or the ways in which Xi’s plans challenge long-gestated ideas of western civilizational supremacy.

The original silk road was an ambiguous network of shifting trading routes, made comprehensible only in the 19th century, when the German scholar Ferdinand von Richthofen came up with the term seidenstraßen to describe them. A similar imaginative exercise in explanation is required today, given that neither the intentions behind this bout of lavish infrastructure spending, nor China’s ultimate objectives when they are all finished, are clearly or honestly articulated by the Chinese themselves.

Ultimately, Frankopan admires the audacity of China’s new empire, and remains oddly sanguine about the new world it might create — as well as ‘the trail of broken promises and the very real frictions’ that Xi’s silk-road building program tends to leave in its wake. The closer that world is connected to China, the more it is likely to take on Chinese traits and to be run along the kind of autocratic, opaque rules China chooses to govern itself. ‘What happens in the heart of the world in the next few years will shape the next hundred,’ Frankopan writes. For many in the West, that isn’t going to be a pleasurable experience.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.