Even rock and roll can have produced few stranger paths than the one that led a then physically unprepossessing, raspy-voiced African-American named Anna Mae Bullock from her early days as a devoutly Baptist sharecropper’s daughter in Depression-era Tennessee, to her final years as a practicing Buddhist living in a whitewashed mansion overlooking the dove-blue haze of Lake Geneva. That was the life trajectory of the artist known to the world as Tina Turner, who died Wednesday at the age of eighty-three.

It seems almost redundant to again trot out the chronology of a life that was chronicled in no fewer than three memoirs, a biopic, a jukebox musical, and the well-received 2021 HBO/Sky joint production Tina, which drew the best TV documentary ratings since the Michael Jackson expose, Leaving Neverland. At one time Turner, like God, seemed to be everywhere, whether it was her face staring back at us through record store windows, or the woman herself strutting across stage in one of her trademark black leather miniskirts and gravity-defying wigs. In the end, she also had the good sense to retire gracefully, rather than to suffer the indignities of other elderly performers going through the motions one more time with their corsets and dubious hairlines. Like professional sport, rock music’s standard currency has always been one of aspirational fantasy, not nuanced reality, and Turner understood the need to preserve her audiences’ image of her better than certain other marquee acts of her era.

The basic facts of Turner’s life can be quickly recalled: born in the one-stoplight town of Nutbush, Tennessee, where her churchgoing ideals were soon compromised by her secular interests, she moved to St. Louis as a teenager, in short order meeting her future husband — the saturnine, guitar-playing Ike Turner – and becoming the only female member of his band, the Kings of Rhythm. It proved a musically fruitful, if personally fraught — and ultimately violent – relationship. “My life with Ike was doomed the day he figured out I was going to be his moneymaker,” Turner wrote in her last autobiography. “He needed to control me, economically and psychologically, so I could never leave him.”

In the end, she did leave, literally running away from her husband following a fight en route to a show in Dallas, with just thirty-six cents in her pocket, setting the stage for an unlikely and prolonged second act as a solo artist. Turner’s musical highpoint during her years with Ike was 1966’s Phil Spector-produced “River Deep — Mountain High”, as well as some notably energetic dates in support of the Rolling Stones, among others. Her personal legacy from the divorce was less impressive: two secondhand cars, and the rights to her stage name.

Turner’s ultimate comeback wasn’t quite as seamless as recalled in one or two of her instant obituaries. She recorded three unsuccessful albums in the late 1970s, but then hit the big time again with 1984’s Private Dancer and its ubiquitous hit single “What’s Love Got to Do with It,” which between them won four Grammy awards, including Record of the Year. One or two churlish critics found they could resist the song itself, with its pedestrian tempo and somewhat cheesy synthesized harmonica solo, but it undoubtedly afforded Turner a new lease on life. Over time she would become a model of endurance in an industry that tends to jettison even its more successful female artists in early middle age. Turner announced her eventual retirement shortly after she turned sixty in 2000, although in true showbusiness fashion she then returned with a farewell tour marking the fiftieth anniversary of her career, synchronized with the compilation album Tina: The Platinum Collection. After that she was content to settle down to a Swiss retirement with her German-born husband Erwin Bach, although it was said that she still sang at her local Buddhist temple, and eventually appeared on four largely chanted albums by Beyond, an all-female group of fellow devotees.

How should we best measure the success of a public entertainer? In Turner’s case, the box denoting sheer scale — she sold over 100 million records worldwide — clearly gets a tick. The style box gets ticked as well, because of the nonstop oomph of her live performances, with their generous quota of flashing video screens, fast-changing lights, lashings of dry ice and other effects, along with the skimpily glittering outfits favored by the artist herself. Also to be considered is sheer resilience: whatever you may think of Turner’s music, it took guts for her to bounce back to the top as she did in her mid-forties, quite apart from her inspirational example to other domestic-abuse victims.

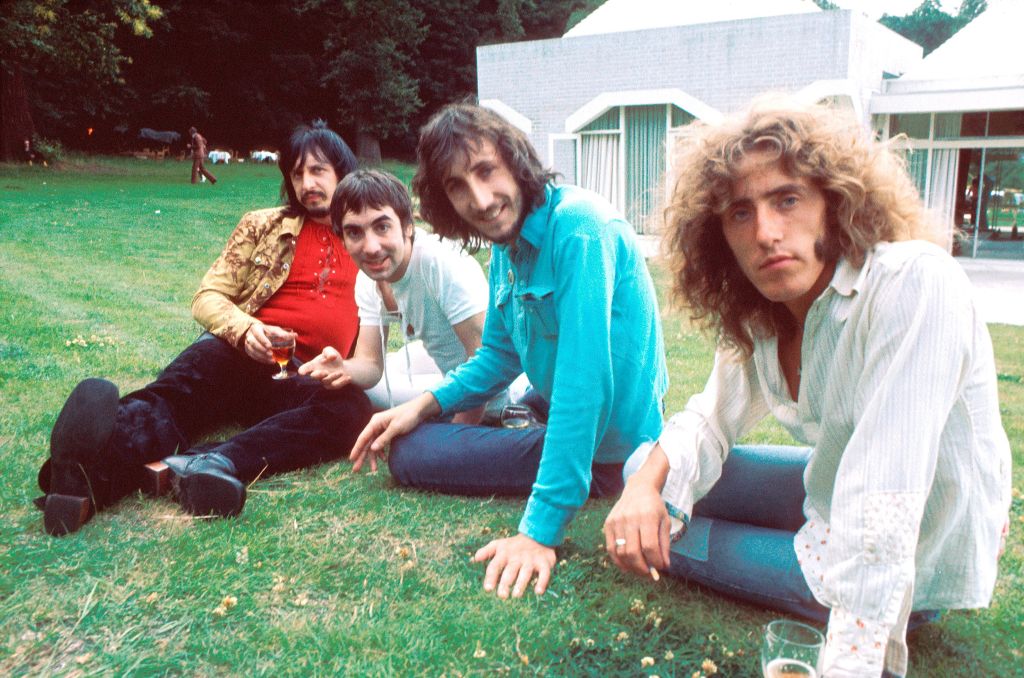

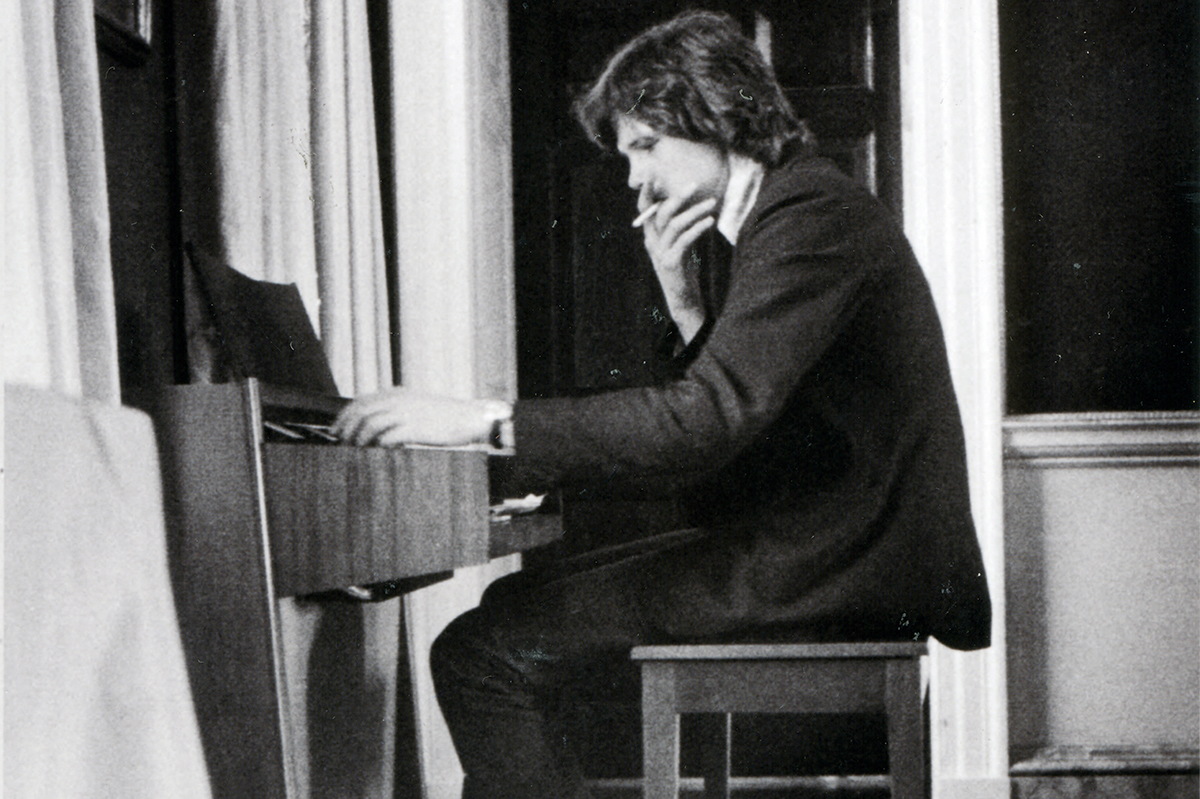

Turner’s influence was also unusually broad, and extends beyond the obvious candidates like Madonna, Lady Gaga and Beyoncé, the last of whom she performed with at the Grammy awards in 2008. The young Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, who spent hours watching in the wings as the Ike and Tina Revue, with their somehow familiar-seeming double act of the gyrating singer and the stony-faced guitarist, went through their paces. Jagger may have enjoyed an even closer relationship even than this with his primary role model. The Rolling Stones’ first tour manager Tom Keylock assured me that he’d once “tripped over Mick and Tina in an extremely relaxed pose backstage at a concert in England.” It may well be true — this was the Sixties — although it would have taken a brave man to risk the wrath of Ike Turner, an artist who once recorded a song which contained the line “Things go better with cocaine” (he died of an overdose in 2007, at the age of seventy-six), and who was at one time arrested for shooting his newspaper delivery-boy for having allegedly kicked his dog.

Perhaps in the end we should remember a different Tina Turner to the high-kicking performer with the big hair. She was something much more universal than that: a survivor.