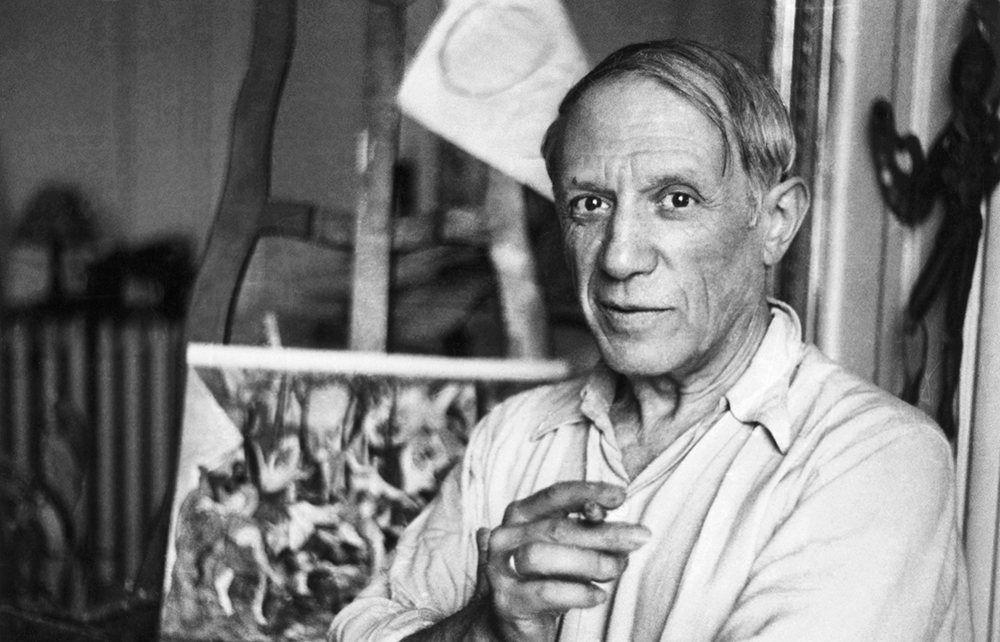

“Well, they can’t cancel Picasso.” That was my optimistic take some months ago when a friend in the art world said: “Watch out, they’re coming for him next.”

It doesn’t really matter that, like Paul Johnson — late of this parish — I don’t feel unadulterated admiration for Pablo Picasso’s work. The late period seems to me a commercial art factory that would have made Andy Warhol blush. But the fact he was a cast-iron genius is beyond doubt, proven by the fact that no one who came after him could go around him. Like Stravinsky in music, you couldn’t continue afterwards as though nothing had happened; Picasso had happened, and for a long time that was that.

If you are a person of exceptional talent it’s expected that you’ll break certain things, including conventions

Everybody always knew that the great Spaniard was not a great human being — and with the fiftieth anniversary of his death this month it appears that those facts are going to be more than rehearsed. Yes, he loved women but did not always treat them well. He could be drunk and despotic. I don’t think anybody within living memory has been surprised by these facts.

I remember George Weidenfeld telling me of a writers’ and artists’ congress that took place in Russia after the last war. By George’s telling, the dinner was made more chaotic — and amusing — by Picasso getting so steamingly drunk that he stripped to his trousers and stormed among his fellow diners informing them that he wanted to leave a baby in Moscow. Perhaps I am less shockable than some people, but I do not find this at all shocking. I think it amusing. Anyway, he was a genius and geniuses are allowed to behave worse than other people.

This last point is a contentious one, but I am willing to defend it. Our culture has always had a genius exemption. If you are a person of exceptional talent it is expected that you are going to break certain things, including conventions. Naturally there is a risk here of people who behave as though they deserve the exemption but are not geniuses. Anyone wondering where this line can be drawn need only study the difference between DJs’ attitudes towards playing Gary Glitter vs Michael Jackson.

That aside, it seems beyond argument to me that genius deserves a leeway which can stretch pretty far. Consider how retrospectives of Caravaggio always talk up his murder of a man as though it is a boon among the master’s achievements; as though there might have been something he saw in those moments which transmogrified into his art and made it worth it.

Or take a less serious but more up-to-date example. Francis Bacon was not just one of the great painters of the late twentieth century but, famously, one of the great drinkers. Four years ago Duncan Fallowell related in these pages an occasion in the Colony Room in Soho when Bacon was pouring Champagne and spilt some on a hand which he promptly shoved down the front of Fallowell’s trousers. “I was only drying my hands,” Bacon said to the younger man, with a grin “like strychnine trying to smile.”

Again, you can laugh about this, as Fallowell did and I would have, or you can tut. But Bacon doing it seems unarguably different from an ordinary pub drunk doing it. It’s also different when it’s a man doing it to a man rather than a man doing something similar to a woman. But the point is not the sexual etiquette. The issue is simply some acceptance that not everybody always behaves perfectly — and geniuses tend to behave less perfectly than others.

Which brings me back to the efforts to cancel Picasso. Some of them come from a recent interview with the remarkable Françoise Gilot, now 101, who has talked about the ten years she spent with Picasso and the two children she had with him before she eventually walked. “I never heard anyone say no to Picasso,” she told the Spanish press last week. “In fact, he called me ‘The woman who says no’ because when I had to say no, I said it.” Good for her. But, as she says, not many people did say no and that gives a chap — especially a genius — a certain license.

So it is that with the fiftieth anniversary of his death, Picasso has been made “problematic” (to use the terrible jargon of our day). The Musée Picasso in Paris has handed its collection over to the bland British designer Paul Smith in an apparent attempt to sanitize itself. Several books attacking Picasso are about to emerge. The Brooklyn museum has announced a commemorative show titled “It’s Pablo-matic.” Curated by an Australian feminist comedian it will apparently feature nearly 100 works, mainly by women artists, looking at Picasso’s “complicated legacy through a critical, contemporary and feminist lens.”

Elsewhere, curators, collectors and critics are lining up to reassess Picasso. One wrote this week that the artist’s reputation has “nosedived.” “When Picasso died at the age of ninety-one the Guardian called him the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Today, Picasso is more often talked about as a misogynist and cultural appropriator, the ultimate example of problematic white guys clogging up the artistic canon.” Those damn white male geniuses, eh?

Another critic has complained: “Even as other ‘great artists’ are beginning to be held to account, Picasso has clung on to his status. Genius transcends misogyny, apparently.”

I suppose if that’s your gig then it’s your gig. But what is this business of holding people (especially geniuses) to account? I’m happy to have great artists be anything — or at least anything but prim, censorious, talentless. Eras tend to produce the artists they deserve. How appropriate that ours would produce a class of person so practiced at “holding to account,” “problematizing” and “re-contextualizing.” People able to do every-thing but create. They are eunuchs trying to take down a bull.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.