In 2011, when the editor of Charlie Hebdo put Muhammad on the cover, he did so as the heir to more than 200 years of a peculiarly French brand of anti-clericalism. Just as radicals in the Revolution had desecrated churches and smashed icons, so did cartoonists at France’s most scabrous magazine delight in satirizing religion. Although Catholicism was their principal target, they were perfectly happy to ridicule Islam too. If Jesus could be caricatured, then why not Muhammad?

Sure enough, one year after the prophet’s first appearance on the cover of Charlie Hebdo, he was portrayed again, this time crouching on all fours and with his genitals bared. The mockery would not cease, so the magazine’s editor vowed, until ‘Islam has been rendered as banal as Catholicism’. This would be, in a secular society, for Muslims to be treated as equals.

Except that they were not being treated as equals. The scorning of Islam was a tradition in France that reached back far beyond the time of Voltaire and Diderot. The earliest European caricature of Muhammad served to illustrate a work by Peter the Venerable, a 12th-century abbot in Burgundy. Peter’s Summa totius haeresis Saracenorum — ‘A Summary of the Entire Heresy of the Saracens’ — did what it said on the tin. Islam was a monstrous perversion of Christian teachings. Not merely a heresy, it was the sump of all heresies. Muhammad, its founder, was ‘the chosen disciple of the Devil’. The caricature of him which accompanied Peter’s text duly showed him as a siren: a monstrous compound of the human and the bestial, luring the unwary to their doom.

This portrayal of Muhammad as a heresiarch, a charlatan who had thrived by twisting the truths of Christianity to his own pestilential ends, was in turn heir to an even older tradition. As John Tolan points out in his new book, condemnation of Islam as a heresy did at least derive from a recognition on the part of Latin Christians that it was not an entirely alien faith: that it honored the biblical prophets; that it laid claim to a divine law; that it was monotheistic.

It had taken time, however, for scholars in the heartlands of Christendom to attain even this degree of familiarity with the beliefs of Saracens. Initially, the assumption had been that — like the Vikings or the Magyars or the Wends — they were pagans. ‘When northern Europeans of the 11th and 12th centuries did hear the name of the Muslim prophet, they often imagined that this “Mahomet” must be the Saracens’ god.’ In French, ‘mahommet’ signified ‘idol’ the whole way through the Middle Ages.

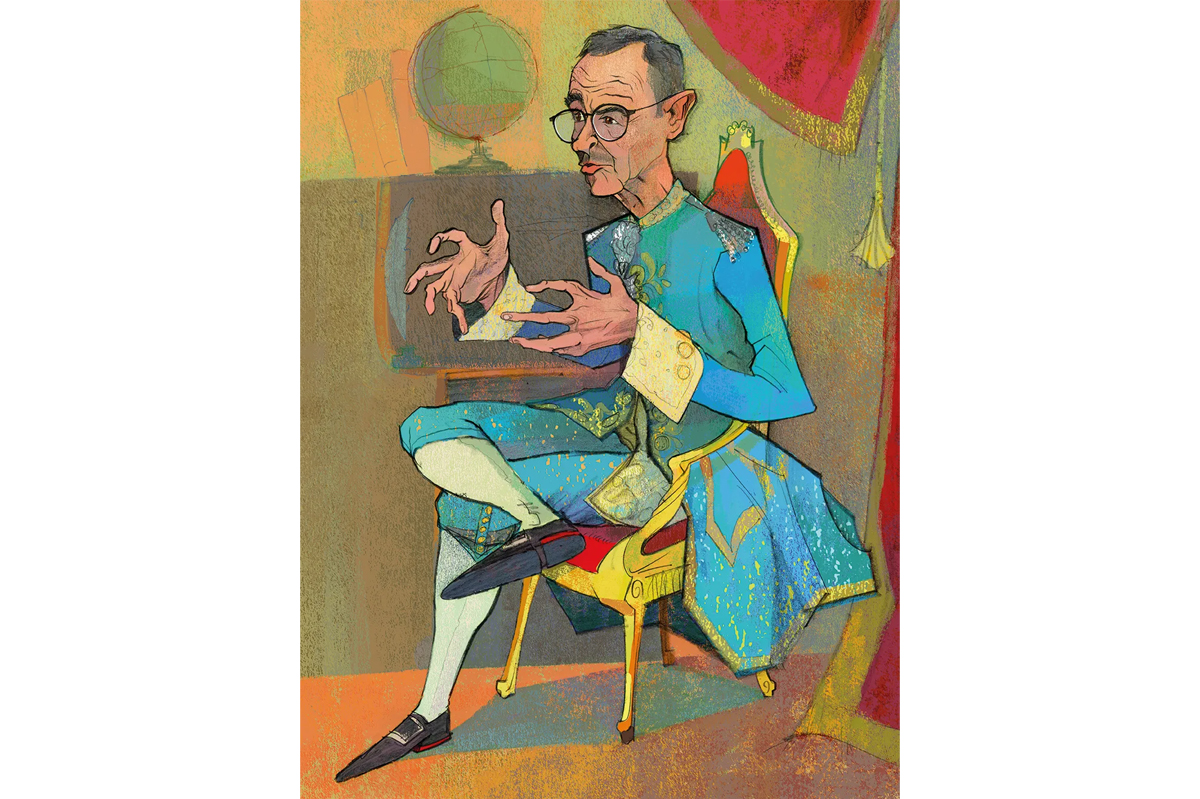

All of which, of course, reveals a good deal more about medieval Christendom than it does about Muhammad himself. In Tolan’s expert study, ‘Western perceptions of the prophet of Islam from the Middle Ages to today’ serve him as an index, not of Islam’s evolution, but of the West’s. Inevitably, the overwhelming impression is of a mingled fear and dislike of the civilization which, from Spain to the Balkans, provided the Christians of Europe with the great counterpoint to their own, a doppelgänger no less universalist and potent in its ambitions than Christendom itself. Tolan shows us a Muhammad made of gold, worshipped in Jerusalem as the Antichrist; a Muhammad who tricks his gullible followers by means of assorted bogus ruses; a Muhammad who is variously epileptic, lecherous and stained in blood. Here is the Muhammad condemned by Peter the Venerable as ‘detestable’.

Yet this is not the whole story. Had it been, then Tolan’s book would not be nearly as interesting as it is. Scholars in medieval and early modern Europe rarely wrote about Muslim history because it was the primary focus of their concerns. ‘Many of these authors,’ as Tolan puts it, ‘were interested less in Islam and its prophet than in reading in Muhammad’s story lessons that they could apply to their own preoccupations and predicaments.’ Peter the Venerable, when he condemned ‘Mahomet’ as the prince of heretics, was quite as anxious to reclaim Spain from the Moors as he was to combat the spread of heresy in Christendom itself. In 17th-century England, pamphlets about Islam were invariably disguised polemics about the monarchy, or Cromwell’s protectorate, or the Church of England. Voltaire’s condemnation of Muhammad as the archetype of fanaticism was aimed, principally, not at Islam, but at that perennial bugbear of his, the Catholic Church.

The result, spanning the course of European history, was a series of engagements with the Muslim prophet that, despite their general tone of hostility, were marked as well by ambivalence and complexity. Increasingly, Muhammad came to serve European intellectuals as a vehicle for their hopes as well as their fears. Even Peter the Venerable, writing to Muslims, sought to win them for Christianity in a spirit of amity — ‘not as our men often do, with arms, but with words; not with violence but reason; not with hate but love’.

In 17th-century England, in the wake of the civil war, hostility to the doctrine of the Trinity led some Protestant radicals to go so far as to compare Islam favorably with the Anglican church. ‘The Arabians,’ wrote Henry Stubbe, author of the first wholly positive biography of Muhammad ever written by a European Christian, ‘liken him to the purest streams of some river gently gliding along, which arrest and delight the eyes of every approaching passenger.’ A century on, and there were many enthusiasts for the Enlightenment similarly delighted by the contemplation of a prophet who had scorned both the metaphysical complexities of Christian theology and the entire apparatus of a priesthood. Even Voltaire, towards the end of his life, was prepared to acknowledge Muhammad as the most brilliant founder of a sect who had ever lived.

This, then, is the 1,000-year line of descent in which Charlie Hebdo stands. Yet if its editor — like Peter the Venerable, like Stubbe, like Voltaire — was chiefly interested in the figure of Muhammad as a mirror held up to his own preoccupations, then no longer is the mirror quite as distant as once it was. What Tolan coyly terms ‘the furor around the caricatures of Muhammad’ —the murder in January 2015 of 12 of the magazine’s staff by two vengeful gunmen — served brutally to demonstrate that ‘Western perceptions of the prophet of Islam’ no longer exist in isolation from the Muslim world. This, of course, had been glaringly apparent for decades — ever since, on Valentine’s Day back in 1989, Ayatollah Khomeini condemned Salman Rushdie to death for blasphemy. The Satanic Verses, the work of a writer obsessed by the interface between the Western and Islamic worlds, was a novel deeply informed by the long history of Christian misrepresentations of Muhammad. But such literary subtleties had cut no ice with the Ayatollah. Unsurprisingly, then, medieval polemics against Islam are a topic that novelists have tended to keep clear of ever since.

Meanwhile, though, in the darker reaches of internet chatrooms and on the stump at far right rallies, they are being given a new lease of life. Tolan, a scholar whose preference is clearly for writing about scholars, avoids concluding his book by exploring just how topical its theme has lately become. Amazingly, he does not mention The Satanic Verses at all. The Charlie Hebdo killings and the Danish cartoons controversy are touched on in only the most gingerly of fashions. The anti-Islamic blogosphere — which at its most extreme has inspired murderous rampages from Utøya in Norway to Christchurch, New Zealand — is dealt with in a mere couple of sentences.

Instead, we get a chapter on the attitude of various 20th-century Christian intellectuals to Muhammad. Interesting though this may be, it is hard not to feel that Tolan has taken his eye somewhat off the ball. Faces of Muhammad is a learned, panoramic and fascinating book. But it is also far more timely than its author seems comfortable acknowledging.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.