Apart from a passionate relationship with the common toad, what do George Orwell and David Attenborough have in common? H.G. Wells is the answer. The self-consciously ‘great’ old man’s bad, yet gripping, writing about utopias profoundly influenced Orwell. And Attenborough, as a lad, was entranced by Wells’s extravaganza A Short History of the World — biology, space science, archaeology, the past and the future, all delivered for children in digestible weekly parts. Attenborough said he derived from it the idea that you ought to know about everything. This ambitious lack of boundaries that they received from Wells liberated both men.

As Dorian Lynskey points out in this idiosyncratic and acutely written ‘biography’ of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, (written to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the book’s publication in June 1949), it was Wells’s cheery dedication to progress that Orwell needed — in order to react against it. Orwell asked in 1943: ‘Is there anyone who wants to live in a Wellsian utopia? … not to wake up in a hygienic garden suburb infested by naked schoolmarms has become a conscious political motive.’

Improbably, the Orwells asked Wells to dinner. The other guest, the startled poet William Empson, who had met Orwell for the first time the day before, watched aghast as it became clear that Wells had read Orwell’s essay ‘Wells, Hitler and World Civilization’ in Horizon, the classy thinking magazine of the decade, which claimed that Wells was ‘too sane to comprehend the modern world’ and that he had been squandering his talents since 1920. Lynskey points out that Orwell was proud of his ‘intellectual brutality’ and that knowing people never compromised his reviews. The argument ended with the two men squaring up with rolled-up copies of Horizon.

Orwell was himself a very sane man who pinned down the vertiginous, slippery descent into ‘glittering’ irrationality that characterized the rise of fascism and populism in the 1930s. Lynskey shows him gnawing away at why there was a market for cruelty and palpable un-truths; why people yearned for leaders; why savagery became an end in itself. He points out that even had Orwell lived, Nineteen Eighty-Four would have been a kind of ending. This last, tight fable was the culmination of the hundreds of thousands of words that Orwell had written before it.

Beside the mighty machine of Orwell’s reading and writing, Lynskey shows that the book was also forged in real history — communism’s betrayal of socialism in the Spanish civil war and World War Two. And Lynskey turns inward, to the direct personal circumstances that made Orwell as he wrote it: ‘the marrow-deep reserve’ that set in when his clever, wry wife Eileen unexpectedly died on the operating table; the bleak reality of being so very ill; and the quotidian satisfaction of being with his son Richard in Barnhill on Jura.

Lynskey indicates, too, that Orwell had a lifelong belief in the value of lived experience and everyday pleasures (those toads again). He disliked intellectuals — but was an intellectual snob. He never ‘truly believed something until he had in some way lived it. In Orwell’s writing, you often meant I’ .

Lynskey is beady about one part of the left’s strenuous attempts to undermine Orwell. He was a passionate socialist, committed to justice, and Lynskey points out a richer, longer story: in a way, Orwell is a kind of litmus test for revealing the narrow grip of orthodoxy. There is the familiar story of the ways in which Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four were rejected by publishers, and how Kingsley Martin, the legendary editor of the New Statesman, turned down Orwell’s essay about Spain. We get Arthur Calder-Marshall’s attack, in Reynolds News, on Orwell’s book and character; the Marxist Quarterly’s hatchet job in 1956: ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four is already on the way out. We need one push to get rid of it altogether’; and finally there were the comments of the much revered Marxist literary critic Raymond Williams, who wrote that Orwell was a road block:

‘If you engaged in any kind of socialist argument there was the enormously inflated statue of “Orwell warning you to go back”.’

Yet Stalin is back in fashion: not just in the Kremlin and the Oval Office or as the play sheet for any number of new authoritarian leaders. It is rumored that the present Labour leader’s office ground to a halt over a bitter dispute about the dictator’s reputation.

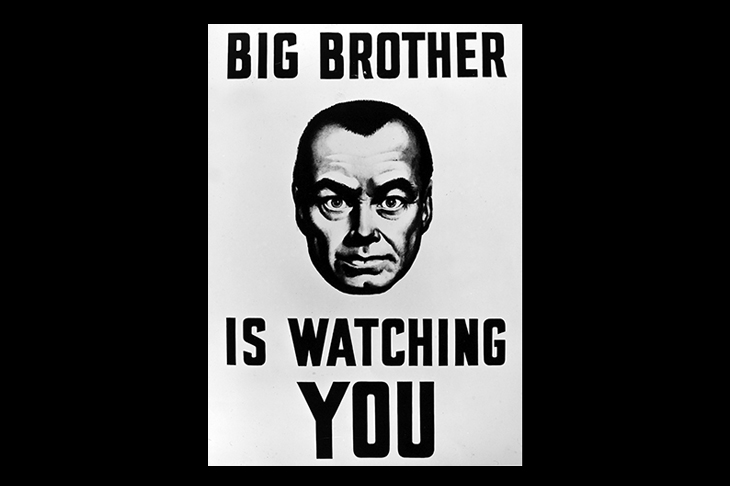

The second half of Lynskey’s book looks at how other artists used Nineteen Eighty-Four and its imaginative landscape. David Bowie, coming out of a period of ‘paranoid, cocaine-maddened, sleep-deprived’ confusion was neurotically unable to fly. So, on the way back from his 1973 Japanese tour, he got the Trans-Siberian railway from Khabarovsk to Moscow. What began as a bit of fun changed Bowie, as he watched the Soviet military parade in Moscow. He tried to write a musical based on Nineteen Eighty-Four (Orwell’s second wife, Sonia Brownell, refused it permission). Lynskey shows how Bowie’s song ‘Somebody Up There Likes Me’ — a brilliant, sinister merging of celebrity, advertising and demagoguery — was a direct response to Orwell. Bowie was putting himself into Big Brother’s brain. Margaret Atwood began writing The Handmaid’s Tale in Berlin in 1984, consciously re-engineering what she took from Orwell with a sophisticated feminist reading of a future.

Lynskey’s biography of the book is personal, and all the better for it — measuring our present against the future set out by Orwell. Dystopias are, he argues, prophylactic. If this future can be described in detail, perhaps it won’t happen. He quotes Orwell saying that ‘liberal values are not indestructible and they have to be kept alive partly by conscious effort’. In other words, the future might be dreadful, it might be ‘swindle, racket and humbug’, unless you do something about it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.