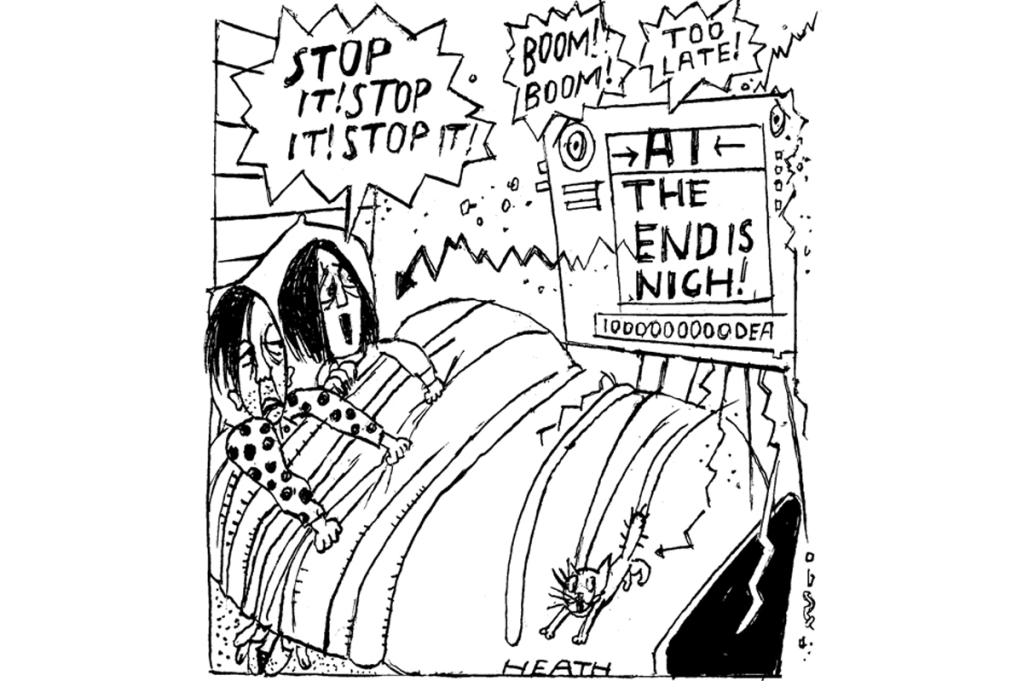

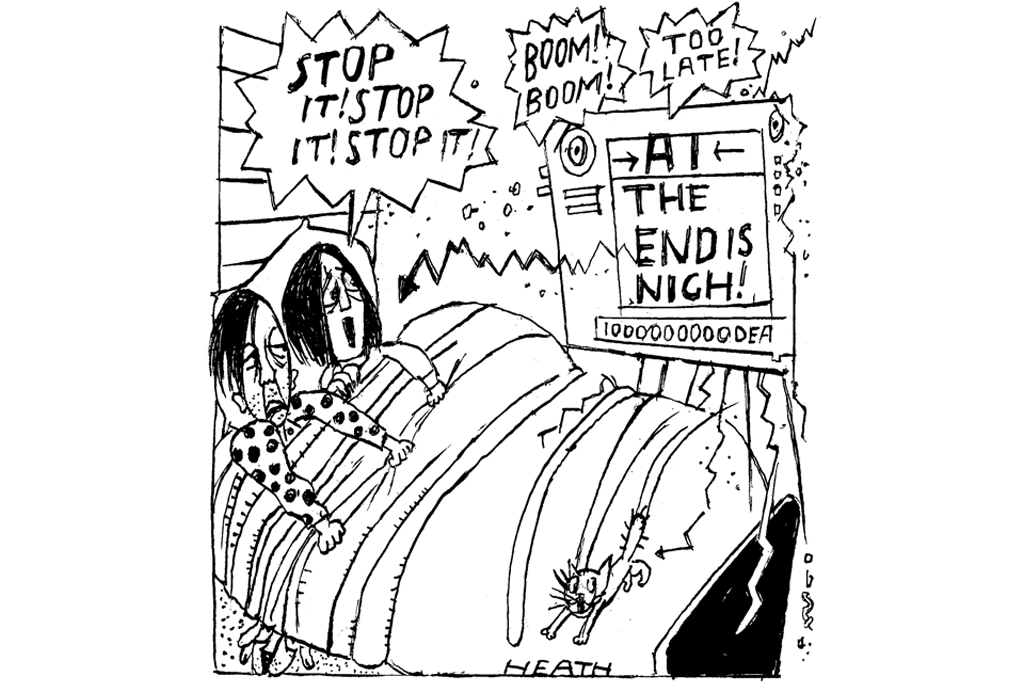

After years of blissful indifference, finally I’m scared of AI. I’ve been complacent, slept soundly beside my husband as he stares and mutters, sleepless with anxiety about robots. But now I’m frightened too. What happened was this.

The sound of a person you love goes straight to your heart. You respond instinctively and emotionally

A few weeks ago a friend received a phone call from her son, who lives in another part of Britain. “Mum, I’ve had an accident,” said the son’s voice. She could hear how upset he was. Her heart began to pound. “Are you OK? What happened?” she said.

“I’m so sorry Mum, it wasn’t my fault, I swear!” The son explained that a lady driver had jumped a red light in front of him and he’d hit her. She was pregnant, he said, and he’d been arrested. Could she come up with the money needed for bail?

It was at this point that my friend, though scared and shocked, felt a prick of suspicion. “OK, but where are you? Which police station?”

The call cut off. Instead of waiting for her son to ring back, she dialed his cell phone number: “Where are you being held?” But this time she was speaking to her real son, not a fake of his voice generated by artificial intelligence. He was at home, all fine and dandy, and not in a police station at all.

Voice scams are on the rise in a dramatic way. They were the second most common con trick in America last year, and they’re headed for the top spot this year. In the UK: who knows? Our fraud squad doesn’t seem to be counting.

It’s just so horribly easy to con people when you’ve an AI as an accomplice. With only a snippet of someone speaking to learn from — a Facebook video, say — an AI tool can produce a voice clone that will sound just like them, and can be instructed to say anything.

In January, a British start-up called Eleven-Labs released its voice-cloning platform. Just a week later someone used it to cook up the voice of the actress Emma Watson reciting Mein Kampf. I didn’t think much of it at the time. Now all I can think of are the millions of elderly parents, the sitting ducks in their sitting rooms, all eager for a call from their kids, all primed.

In Canada, an elderly couple called Perkin were conned out of $21,000 in a scam nearly identical to the one my pal went through. One afternoon they received a call from a man who said he was a lawyer and told them that their boy had run over a US diplomat. The lawyer passed the phone to the “son” who told his frightened parents that he loved them and that yes, he urgently needed cash. What did they know? It was their son’s voice, says Mrs. Perkin. They paid up, and now the money’s gone. No one’s liable.

Even after she knew it was a con, she still couldn’t shake the feeling that she’d spoken to her son, says Mrs. Perkin. And this is what seems so brutal to me about deepfake voices. If you love a person, the sound of them goes straight to your heart. You respond instinctively and emotionally.

If I even imagine taking a call from my husband, hearing him tell me that my son’s been hurt, my blood pressure rises. I’d send him my bank details in a heartbeat, and if I thought to pause to check his identity, that in itself would feel wrong. “Logic wasn’t even helping me,” says my friend of her experience, “because one of my ‘logical’ thoughts was that the voice was too much like M not to be him. I thought I was just grasping for any excuse to not believe what I was hearing.”

Now that it’s obvious how easily AI can hack into and manipulate human emotions, I feel daft for not being afraid before. For that, I blame memes and porn.

We’ve all known about deepfake video for a while. One famous clip shows a very real-looking Tom Cruise playing pranks, doing magic tricks and eating lollipops. I’ve been reassured by this because on close scrutiny it’s clearly not actually Tom Cruise. No AI-generated Tom can replicate the real one’s look of suppressed rage; the scalding contempt in which the original holds ordinary humans.

Obviously, predictably, most of the demand for deepfake video has been in pornography. In 2019 it was estimated that a very amusing 96 percent of deepfake material online is porn. There’s a lot of media fuss about deepfake sex tapes but again, this doesn’t worry me one jot. It’s a self-correcting problem: the more people know about the possibility of pornographic deepfakes, the more plausible any denial — even when the footage is real.

In January a gamer called Brandon Ewing — online name “Atrioc” — was busted with deepfake pornography of his female colleagues and friends. The colleagues and friends said they were angry and hurt but… what did they think would happen? There’s a reason deepfake video services are advertised on Pornhub.

But anyway — who cares about sex tapes really? It’s the parents and grandparents I mind about, and in this new world of AI crime they’re almost completely alone. There’s nothing the cops can do, except to insist that they’re recruiting “cyber-experts” and that the fraud squad is “taking it very seriously.” It’s going to be up to you and me to warn our relatives. I can’t see it going so well.

“Mum, if you hear me on the phone saying I’ve had an accident, be careful…”

“You’ve had an accident?”

“No Mum, it’s just, if I ask for money, make sure it’s me.”

“You need money, darling?”

I lie awake now next to my husband, both of us sleepless in the half dark. I imagine all the ways in which deepfake audio could be used. I imagine a call in later life from a spoofed number: “Hi Mum, I’m just at the front door. Can you come down and let me in?”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.