One autumn night in 1991, I stood on the rooftop terrace of a tacky villa in Saranda once owned by Albania’s Stalinist dictator Enver Hoxha, beside three elderly former SOE officers who were returning to Albania for the first time since 1945. In an image that summed up the waste and the horror of the Cold War, David Smiley stared out over the dark water at the lights of Corfu, from where, on a similar night in October 1949, he had sent a group of dissidents, code-named the ‘Pixies’, to launch an insurgency — and wiped his eye in silence.

Smiley’s men had been ambushed as they landed, and then killed, on the tip-off from Kim Philby, the highest Russian agent to infiltrate British Intelligence, and in charge of anti-communist espionage. It was left to Smiley’s fellow SOE companion, Julian Amery, to murmur reflectively: ‘We might have saved Albania. We didn’t, and Albania became the Orwell caricature of communism.’

Philby looms large in Duncan White’s ambitious and constantly rewarding survey of writers who battled to get read in the Cold War. Although not strictly speaking an author, Philby was a mark of how far each side was committed to penetrating, understanding and subverting the other; a perversion, if you like, of the empathy that is the writer’s necessary condition, and which defines White’s chiefly Anglo/Soviet cast of novelists, poets and playwrights.

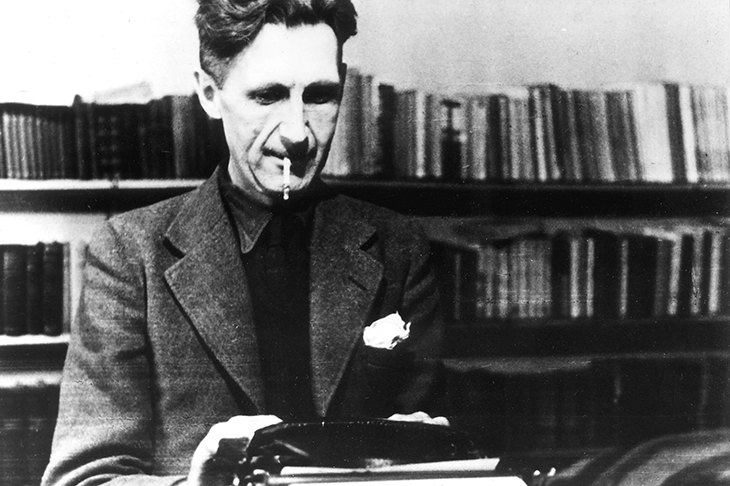

In the wake of the second world war, Russia and the West feared the domino effect of enfeebled countries like Albania falling into the clutches of imperialist capitalism or communism. Each side deployed literature as a frontline force in their struggle. For the CIA, which covertly funded magazines such as Encounter and Mundo Nuevo, books were ‘the most important weapon of strategic (long-term) propaganda’; for Alexander Solzhenitsyn, in a different context, his precious notes and drafts of The Gulag Archipelago ‘were as dangerous as atom bombs’. Books were lobbed into enemy territory like grenades. Between 1952 and 1957, from three sites in West Germany, a CIA operation codenamed ‘Aedinosaur’ launched millions of ten-foot balloons carrying copies of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, and dropped them over Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia — whose air forces were ordered to shoot the balloons down.

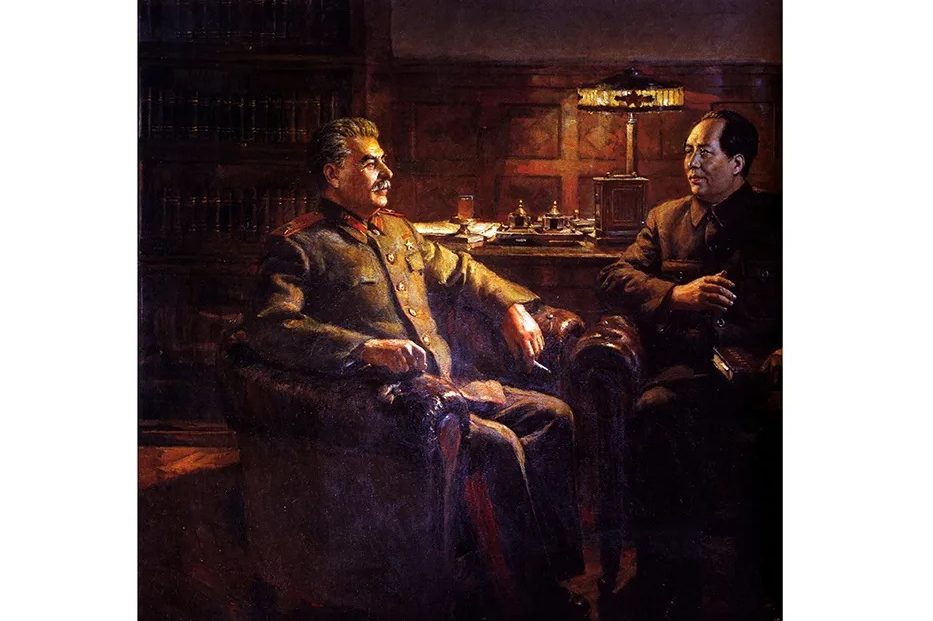

It was Orwell, ‘the iconic writer of a generation’, who gave the Cold War its name. He had had his acidic baptism in the Spanish Civil War, alongside Arthur Koestler and Stephen Spender. ‘We started off by being heroic defenders of democracy, and ended by slipping over the border with the police panting on our heels.’ Even though he had been shot in the throat by a nationalist bullet, Orwell was denounced as a ‘confirmed Trotskyist’ by a fanatical English communist, David Crook, who had been recruited to Stalin’s NKVD by the agent who later assassinated Trotsky, Ramón Mercader — and whose unrepentant Canadian widow I met years later in Beijing, where she and Crook were imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution. It had not altered the course of her reverence. ‘When I was locked up, I read Volumes I-IV of Mao’s complete works three and a half times.’ And? ‘I loved his rare shafts of humor.’

Isabel Crook had obliterated from her memory how humor was a dangerous commodity in the Cold War. Along with 2.4 million others, the poet Osip Mandelstam was incarcerated for an epigram he wrote about Stalin’s grub-fat fingers — as was Solzhenitsyn, for cracking a joke about Stalin. Distinctly shy of humor was Mikhail Gorbachev, the Russian leader who did more than anyone to end the Cold War. When Václav Havel, the Czech playwright-turned-dissident-leader, suggested coming to Moscow to smoke with him a ceremonial pipe of peace that Havel had been given by a North American tribe, Gorbachev stammered: ‘But I… I don’t smoke.’

For all its balloon-filling hot air, the Cold War was a deadly serious affair, even if it seemed hard to take seriously early on. Orwell’s factual account of his experiences in Spain, Homage to Catalonia, sold just 638 copies. Only when he was sent for review Koestler’s fictionalized account of the same conflict, Darkness at Noon (half a million copies were sold in France alone), did he recognize that fiction, rather than journalism or memoir, was, in White’s words, ‘the most effective way to communicate the essence of totalitarianism’.

The American novelist Mary McCarthy later explained it like this:

‘Readers put perhaps not more trust but a different kind of trust in the perception of writers they know as novelists… What we can do, perhaps better than the next man, is smell a rat.’

Written to undermine Stalinism and the rabid purges that Orwell witnessed in Spain — ‘the special world created by secret police forces, censorship of opinion, torture and frame-up trials’ — Animal Farm was completed in three weeks. Nineteen Eighty-Four took three years longer. Published in 1949, and set, not in Russia, but in a future Britain which, White nicely reminds us, had become a mere colony of the US, renamed ‘Airstrip One’, it was immediately recognized as ‘the most powerful weapon yet deployed in the cultural Cold War’.

Behind the Iron Curtain, Stalin’s chief cultural propagandist, Andrei Zhdanov, insisted that Soviet literature was ‘the most advanced literature in the world’ because ‘it does not and cannot have other interests besides the interests of the state’. In pursuit of ‘socialist realism’, brigades of writers were encouraged to write collective novels about the factory to which they had been assigned. The penalty for not doing so was in general as dire as the result. The poet Anna Akhmatova, who, like Solzhenitsyn, had to tear up and swallow or bury her work, reckoned that ‘not a single piece of literature’ was printed under Stalin’s poisonous rule.

One of myriad mediocre talents hitched to communism’s disintegrating band-wagon was the Russian novelist Alexander Fadeyev. Co-founder and chairman of the Union of Soviet Writers, he had signed letters which led to his fellow authors being arrested, and sometimes worse: an estimated 1,500 writers lost their lives in Stalin’s purges, among them Mandelstam, Isaac Babel and Boris Pilnyak. But the price of selling his soul to ‘the satrap Stalin’ became too high, and on May 13, 1956 Fadeyev shot himself. His suicide note mourned how literature had been ‘debased, persecuted and destroyed’, and the best writers ‘physically exterminated’.

Dissident writers were treated less barbarically in America. One famous leader of the communist cause was Howard Fast, who at a protest against anti-communists was observed ‘fighting with a Coke bottle in each hand’. Still, his books were burned and removed from libraries in Senator Joe McCarthy’s witch-hunt, and Fast was sent to prison at Mill Point where he conceived his novel Spartacus, which became a self-published bestseller and Hollywood movie.

Nor was the US spared its enemy’s hypocrisies and complicities. America’s declared pre-war wish to champion self-determination lost out to the stronger impulse to contain the spread of communism and find new resources, as in oil-rich Iran, where a joint CIA–SIS coup toppled the elected leader. Elsewhere, America propped up repressive right-wing dictatorships in South Vietnam (as fictionalized in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American), Cuba (Our Man in Havana) and South and Central America, the supreme act of hypocrisy being the Iran-Contra Affair.

It’s a big subject. White wants us never to forget that ‘the Cold War was a conflict of truly global scope’, and though not pretending to be comprehensive, his research is impressive, presented in crisp, efficient prose with an eye for the encapsulating detail (e.g. Ho Chi Minh catching frostbite while queuing to pay homage to Lenin’s corpse). Even so, his parameters are a bit loosey-goosey. While prepared to bring Nicaragua into his sphere of interest, he strangely neglects to travel further south, most glaringly to Chile, where the CIA’s overthrow of the communist president Salvador Allende merits just half a paragraph.

Many of this period’s outstanding writers were the products of Latin America’s Guerra Fría, yet White finds no space for Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, Gabriel García Márquez or Guillermo Cabrera Infante. Nor does China get a look-in; or East Germany, where writers such as Christa Wolf became irrelevant overnight once the Berlin Wall was broached. A further absence is a considered voice from the other side — for example, a poet like Yevgeny Yevtushenko, who appeared to straddle the divide; or a representative of the victorious Spanish Nationalists like the novelist Camilo José Cela, a censor for Franco who in the epochal year of 1989 won the Nobel Prize. Perhaps the subject is too big.

That said, Cold Warriors fascinates in the areas it does choose to cover, and serves as a nostalgic reminder of a time when literature was a life-or-death matter. White writes: ‘It is hard to imagine the publication of a novel precipitating a geopolitical crisis in the manner of Dr Zhivago or The Gulag Archipelago.’

As for the future, Václav Havel, the Czech writer who lived to become president, predicted two possibilities only. Either ‘the independent life of society’, that seemed won when the Cold War ended, will grow and grow until society changes. Or else, we are doomed to face what happened in Albania — ‘some dreadful Orwellian vision of a world of absolute manipulation’.

This article was originally published in The Spectator‘s UK magazine.