Peter Schjeldahl’s essay ‘Renoir’s Problem Nudes‘ in The New Yorker has already attracted some portion of the contempt and ridicule it deserves. Here is my modest contribution to that task.

According to Schjeldahl, Renoir ‘sparks a sense of crisis.’ ‘Who doesn’t have a problem with Pierre-Auguste Renoir?’ he asks in his opening gambit. Can we have a show of hands on that? Pace Schjeldahl, Renoir is such an immensely popular because his painting is essentially celebratory; he looked upon the world with an oeil bienveillant, glorying in its sumptuousness. There is great intensity in some of Renoir’s portraits, but very little melancholy. The dominant mood is festive: a happy, sociable sensuousness.

You would not know this from Schjeldahl’s account. Renoir’s reputation, he asserts, ‘has fallen on difficult days.’ This is partly because of ‘class’ issues: Renoir, son of a tailor and a seamstress, ‘was bourgeois by aspiration’ rather than origin. Imagine: he actually celebrated prosperity.

Bad though that is for the virtue-signaling mandarins who read The New Yorker, much worse was his unenlightened attitude towards women. Renoir liked them, you see, but not in the way that people like Peter Schjeldahl can countenance. ‘In contemporary discourse,’ Schjeldahl observes, Renoir has ‘come to stand for “sexist male artist.”’ Uh oh.

Schjeldahl proceeds to dilate on the ‘presumptuous, slavering joy’ Renoir took in ‘looking at naked women,’ a joy sharply at odds with his actual painting, which, according to Schjeldahl, features ‘monotonously compact, rounded breasts and thunderous thighs, smushed into depthless landscapes and interiors…their faces nearly always look, not to put too fine a point on it, dumb.’ Renoir was adept at the difficult job of rendering hands, Schjeldahl grudgingly admits, but that was only to remind us that female hands are ‘good for doing things, perhaps around the house.’ Final verdict: Renoir’s attitude was ‘worse than misogyny.’

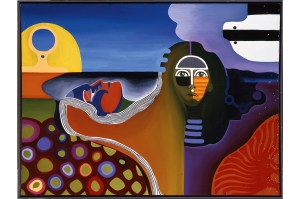

Let’s pause for a quick reality check. Consider, to take just one example, Renoir’s 1875 painting ‘Avant le bain,’ from the Barnes collection.

Notice any slavering? Monotony about the breasts? Any dumbness about the face?

Schjeldahl’s judgments about Renoir are a fastidiously composed congeries of up-to-the-minute elite opinion. There at The New Yorker, everyone will agree with Schjeldahl about Renoir or — the more important point — about subjugating him to the strictures prevalent among the beautiful people circa 2019. What made Schjeldahl’s essay notorious were not his particular judgments about Renoir’s art or character but rather his imperative anachronism. ‘An argument is often made that we shouldn’t judge the past by the values of the present,’ Schjeldahl writes, ‘but that’s a hard sell in a case as primordial as Renoir’s.’

Is it? As Ed Driscoll pointed out at Instapundit, Schjeldahl’s essay is sterling example of what C.S. Lewis described as ‘chronological snobbery,’ the belief that ‘the thinking, art, or science of an earlier time is inherently inferior to that of the present, simply by virtue of its temporal priority or the belief that since civilization has advanced in certain areas, people of earlier time periods were less intelligent.’ If, Driscoll observes, we add the toxic codicil that those previous times were ‘therefore wrong and also racist’ we would have ‘a perfect definition of today’s SJWs.’

Exactly. Driscoll goes on to quote Jon Gabriel, who has anatomized this process under the rubric of ‘cancel culture,’ a culture of willful and barbaric diminishment.

‘Cancel culture,’ Gabriel notes, ‘is spreading for one simple reason: it works. Instead of debating ideas or competing for entertainment dollars, you can just demand anyone who annoys you to be cast out of polite society.’ It’s already come to a college campus near you, and is epidemic on social and other sorts of media. not to mention through the so-called ‘Human Resources’ departments of many companies. Wander ever so slightly outside the herd of independent minds and, bang, it’s ostracism or worse.

There are many ironies attendant on the spread of ‘cancel culture.’ One irony is that, despite its origins in the effete eyries of elite culture, the new ethic of conformity exhibits an extraordinary and intolerant provincialism. The British man of letters David Cecil got to the nub of this irony when, in his book Library Looking-Glass, he noted that ‘there is a provinciality in time as well as in space.’

‘To feel ill-at-ease and out of place except in one’s own period is to be a provincial in time. But he who has learned to look at life through the eyes of Chaucer, of Donne, of Pope and of Thomas Hardy is freed from this limitation. He has become a cosmopolitan of the ages, and can regard his own period with the detachment which is a necessary foundation of wisdom.’

It has become increasingly clear as the imperatives of political correctness make ever greater inroads against free speech and the perquisites of dispassionate inquiry that the battle against this provinciality of time is one of the central cultural tasks of our age. It is a battle from which the traditional trustees of civilization — schools and colleges, museums, many churches — have fled. Increasingly, the responsibility for defending the intellectual and spiritual foundations of Western civilization has fallen to individuals and institutions that are largely distant from, when they are not indeed explicitly disenfranchised from, the dominant cultural establishment. Leading universities today command tax-exempt endowments in the tens of billions of dollars. Leading cultural organs like The New Yorker and The New York Times parrot the ethos of the academy and exert a virtual monopoly on elite opinion. But it is by no means clear, notwithstanding their prestige and influence, whether they do anything to challenge the temporal provinciality of their clients. No, let me amend that: it is blindingly clear that they do everything in their considerable power to reinforce that provinciality, not least by their slavish capitulation to the dictates of the enslaving presentism of political correctness.

The reputation of Pierre-Auguste Renoir can fend for itself, no matter the childish depredations of feminist aspirants like Peter Schjeldahl. The hilarious idea that Renoir’s art was an example of misogyny — or of something ‘worse than misogyny’ — could only occur to someone so besotted by the feminist deformations of political correctness that he had blinded himself to basic human realities that have been obvious to candid observes since before the author of the Book of Genesis recorded the drama of Adam and Eve. An art review in an increasingly irrelevant bulletin of sclerotic orthodoxy may seem beside the point. In substance, it is. But considered as a symptom, a bellwether, it another grim reminder of cultural disintegration and therefore worth all of the obloquy we can muster.