AD 79: Pliny the Elder, admiral of the Roman fleet and author of an encyclopedia of Natural History, sails towards Mount Vesuvius as it erupts.

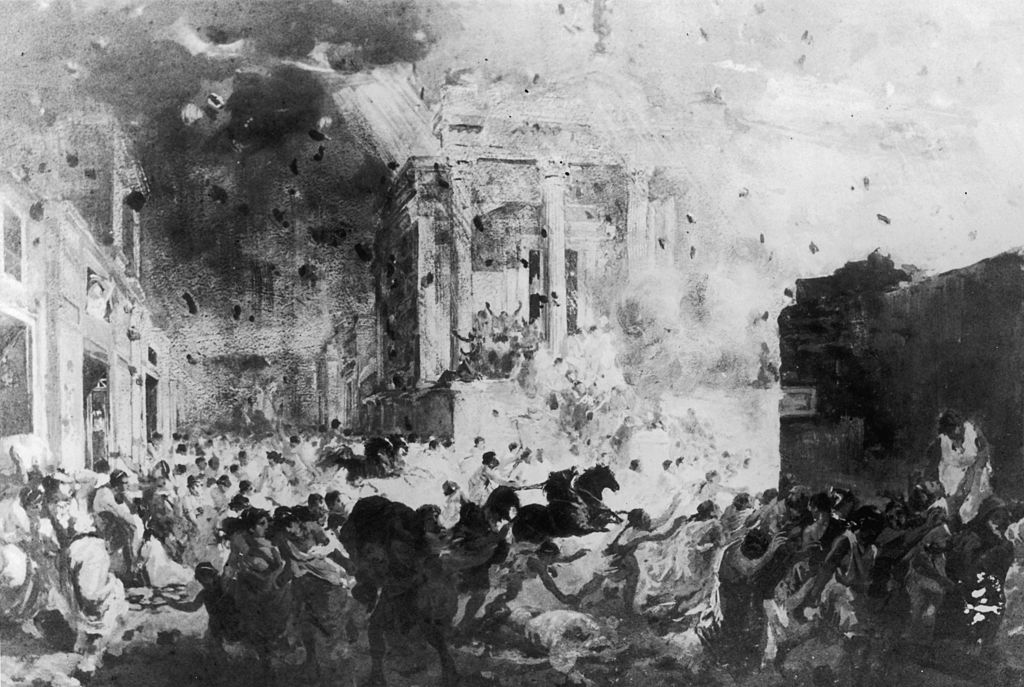

For several hours, the fleet held course across the Bay of Naples. Despite heading in the very direction whence others were now fleeing, Pliny the Elder was said to have been so fearless that ‘he described and noted down every movement, every shape of that evil thing, as it appeared before his eyes’. To any sailors who survived to tell the tale of their admiral’s fortitude, the chance of reaching land in safety must have seemed increasingly remote as they proceeded across the water. First ash rained down on them, then pumice, then ‘even black stones, burned and broken by fire’. This was no hail storm. The fall of grey-white pumice is thought to have lasted eighteen hours in total. By the time the ships had come within sight of the coast, the pumice had formed island-like masses on the sea, impeding them from advancing any further. When the helmsman advised turning back, Pliny the Elder adamantly refused. ‘Fortune favors the brave,’ he said.

They determined to put in where they could. Stabiae, a port town just south of Pompeii, lay about 16 kilometers (10 miles) from Vesuvius. As ash and pumice continued to pour down, Pliny the Elder went to find a friend, Pomponianus, who had already stowed his possessions aboard a ship, ‘set on flight if the opposing wind settled’. Pliny the Elder embraced him and requested a bath before joining him for dinner. ‘Either he was content,’ his nephew speculated later, ‘or he showed a semblance of contentment, which was just as great-hearted.’ As his host and his household watched flames leaping from the mountain and lighting up the night sky, Pliny the Elder told them that they were witnessing merely ‘the bonfires of peasants, abandoned through terror, and empty houses on fire’. As if soothed by his own deception, he soon fell asleep.

He was 55 years old, corpulent and had a weak windpipe. As the hot ash and pumice began to mount up on the pavement outside the doorway, his raw and narrow airways — call it asthma — for once proved to be a blessing. He might have been trapped inside had his noisy breathing not alerted Pomponianus’s household to his continued presence inside the house. Rousing him from his bedchamber, they gathered to make a final decision as to whether to stay put or leave while they still could. The weight of the pumice and repeated earth tremors had now begun to cause buildings to collapse. If they remained in the villa they might be crushed. If they ventured outside, then the pumice could still throw other structures down on top of them. About two meters (6’6″) of it would fall on the town of Stabiae alone.

As the earthquakes started to intensify across the Bay of Naples, buildings seemed to be swaying on their foundations and collapsing from their debris-laden roofs. Pliny the Elder remained sufficiently rational to realize that to stay inside, while the earth shook and the sky fell in, would be fatal. He, Pomponianus and the other men and women in the house gathered up pillows, strapped them to their heads, and ventured out into the darkness. Pumice is light and porous but a large piece of volcanic rock might easily have felled them.

When morning rose over Stabiae, it was unlike any morning the people had known. It was like night, only ‘blacker and denser than all the nights there have ever been’. Pliny the Elder took a torch and made his way to the shore to see whether there was any chance of escape. The sea was wild. The wind was against them. And so he lay down on a cloth on the beach. He called out once, then a second time, for some cold water. And he waited…

Pliny the Elder was a scholar as well as an admiral. An exception to his own rule that ‘there is nothing in Nature that does not like the change provided by holidays, after the example of day and night’, he worked through darkness and daylight. He was not like the beasts of burden who ‘enjoy rolling around when they’re freed from the yoke’, or the dogs who do the same after the chase, or the tree that ‘rejoices to be relieved of its continuous weight, like a man recovering his breath’. Believing that a moment away from his books was a moment wasted, he had developed an extraordinary ability to study in any situation: not only while he ate and while he sunbathed, but even while he was rubbed down after his bath (he used to pause only for the bath itself). On one occasion when he was taking notes over dinner, a guest deigned to correct the pronunciation of the slave who was reading to them from a book: ‘But you must have understood him?’ Pliny the Elder asked. ‘Then why did you make him repeat the word? We have lost at least 10 verses because of your interruption!’ His nephew, Pliny the Younger, remembered how he used to chastise him for walking everywhere when he might have travelled by sedan chair, as he did, ‘You could avoid losing those hours!’

A furious night-writer, Pliny the Elder was fortunate to possess ‘a sharp intellect, incomparable concentration, and formidable ability to stay awake’. There were moments when he nodded off during the day, but these were as nothing to the time other people wasted. If his passion for night-writing was born of necessity, then it was driven by the need he felt to make the most of the time he had. Humans are not wronged by the fact that their lives are brief, he wrote, but do wrong by spending the life they do have asleep. For to sleep is to lose half of one’s allotted time — more than half, given that infancy, ailing old age, indeed the hours lost to insomnia, cannot truly constitute living. He went so far as to establish a memorable formula to express these beliefs. Vita vigilia est, he wrote: ‘To be alive is to be awake’.

The idea was a logical solution to a theme found in Homer. If wakefulness was life, then it was because sleep was akin to death. The Homeric epics taught that Sleep and Death were brothers. When Zeus’s mortal son Sarpedon falls at Troy in the Iliad, Sleep and Death carry his body from the battlefield. A painting of them straining beneath the weight of the warrior’s bleeding corpse became the unlikely adornment for a wine bowl in the late 6th century BC. The brothers are formidable figures, with richly textured wings, armored body plates and long dark beards. One grasps Sarpedon’s legs, the other his gigantic shoulders, while blood gushes from his wounds like wine from a ruptured wine skin. Distributing his weight between them, Sleep and Death raise him from the ground as the god Hermes watches. There is life in Sarpedon’s tendons yet, but his head is slumped, the final insult to the divine father who could not save him. To preserve what is left of his dignity, Sleep and Death must carry his body to his native Lycia for burial.

Sleep and Death were united in Pliny the Elder’s mind in the same way as they were on the archaic pot. They were strange and inimitable brothers, shadows of one another, complementing each other in their work. To embrace Sleep as the brother of Death was to recognize wakefulness as the sister of life.

Pliny the Elder’s nephew, Pliny the Younger, was a lawyer, senator, collector of villas, curator of drains, and personal representative of the emperor overseas. Inspired by his uncle’s choice of life over deadly sleep, Pliny the Younger established a rigorous routine of his own. In the winter months he rose early, albeit some hours later than his uncle, and worked continuously throughout the day, dispensing with both the afternoon siesta and after-dinner entertainment he normally enjoyed in summer in order to persevere with his notes. His uncle shielded his hands from the cold with gloves, ‘so that not even the bitterness of the weather could snatch any time away from his studies’. The younger Pliny relied on his underfloor heating.

There is no clearer reflection of the kind of orderly, upright and morally unblemished life the younger Pliny aspired to live than in his descriptions of his occasional dinners. He was almost irritatingly exacting about their composition. However much he tried to make light of it with his friends, there was no concealing the pedant inside him:

To Septicius Clarus,

How dare you! You promise to come to dinner, but never show up? Here’s your sentence: you shall reimburse the full costs to the penny. They’re not small. We had prepared: a lettuce each, three snails, two eggs, spelt with honeyed wine and snow (you shall pay for this too, a particular expense since it melts into the dish), olives, beetroot, gourds, onions, and many other choice items. You would have heard a comedy or a reader or a lyre- player or – if I was feeling generous – all three. But you no doubt chose instead to dine with someone who gave you oysters, womb of sow, sea urchins and dancing girls from Cadiz . . .

Plinius.

Lettuce, snails, eggs, spelt, snow, olives, onions: these were his hors d’oeuvres. Too frugal to be particularly appetizing and too precise in their arrangement to put a man at ease, they were the plate form of Pliny the Younger’s considered and compartmentalized life. Lettuce, sown upon the winter solstice, was served to aid digestion, promote sleep, and regulate the appetite (‘no other food stimulates the palate more while also curbing it’). Eggs soothed the stomach and throat. Olives were picked for salt, and onions sliced for sweetness. Not too much of anything. Each ingredient was self-contained and recognizable to the Roman eye, the snow alone seeping everywhere.

Perennially attracted to the idea of a quiet retirement spent enjoying books, baths and country air, Pliny the Younger also savored the spice of Rome and had ambitions of becoming a famous poet. He was forever darting between the city, coast, countryside and lake and adapting his daily routine to each. It felt as natural to him to change houses and rooms through the year as it did to the Roman general who asked Pompey the Great, ‘Do I seem to you to have less common sense than the cranes and storks and thus not to change my living arrangements in accordance with the seasons?’ Believing that a man is happiest when he can be confident that this name will live forever, Pliny the Younger was strategic in the ways he divided his time. The problem was that he wanted eternal fame and daily contentment. His life was in many ways an exercise in how to achieve both.