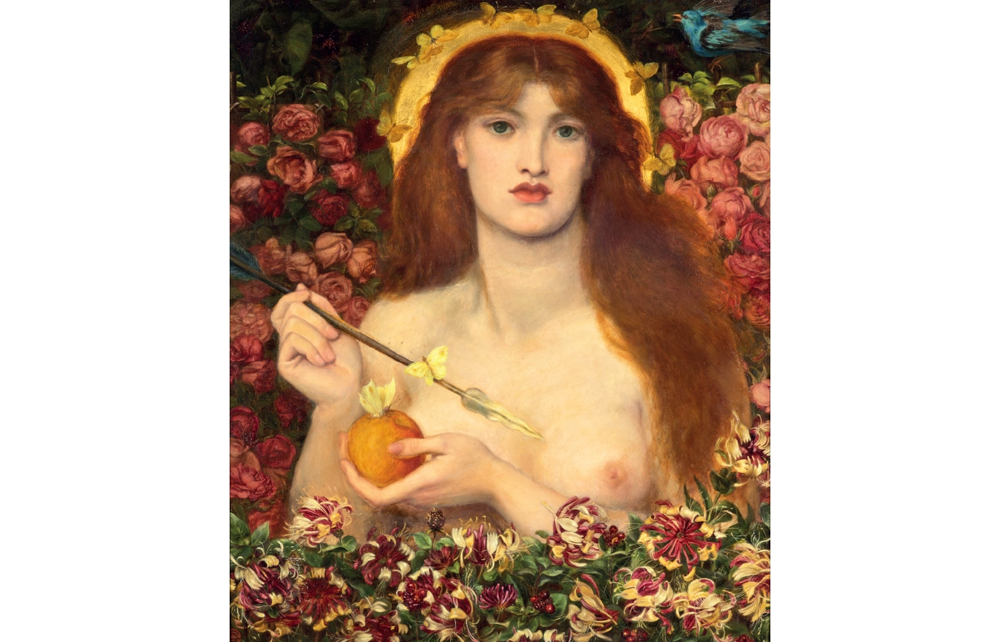

You may think that roses have always symbolized courteous romance, but art history describes their smuttier private life. Consider the pouting red blooms in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Venus Verticordia,” which the art critic John Ruskin considered so obscene that he refused to continue his friendship with the painter. Ruskin admired the execution when he first saw “Venus Verticordia” in Rossetti’s studio in 1865, but later reviled the crude suggestiveness. “I purposely used the word ‘wonderfully’ painted about those flowers,” he later wrote to Rossetti with deep concern. “They were wonderful to me, in their realism; awful – I can use no other word — in their coarseness.”

Ruskin’s anxiety reflected a common understanding of the red rose as a symbol of lust. The Victorian period witnessed a fad for floral symbolism, and multiple books were published to define the “language of flowers.” The red rose was deemed scandalously sensuous. The association persisted into the modern world. According to a well-known rumor, the enigmatic “Rosebud” of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane alluded to a private joke. William Randolph Hearst, the inspiration for the character of Charles Foster Kane, used it as the codeword for the pudenda of his mistress, Marion Davies.

The link between roses and lewdness extends like a taproot back into the classical world. In the poetry of Sappho from the sixth-century BC, there are references to planting roses at the shrine of Aphrodite, goddess of love and sexuality. Aphrodite and her Roman equivalent Venus are therefore usually accompanied by velvety-petalled roses when they are represented in art, as you can see in Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus” and Titian’s ‘Venus of Urbino.”

Ancient Greek poets such as Sappho and Anacreon inaugurated the association between roses and love. But in the hands of Roman historians, roses became linked to decadence, immorality, and rampant sexual desire. This reflects a more widespread Roman cultural obsession with roses, which they farmed in the flushed fields of Egypt and Spain and imported on an industrial scale. Our modern transnational flower industry is no different. As many as 250 million roses are harvested for Valentine’s Day from climate-controlled farms in Colombia, Kenya and the Netherlands, and delivered at the perfect moment in their lifecycle to customers across the globe.

In Horace’s Odes, roses are consistently presented in the context of love affairs and sumptuous feasts. According to Suetonius, Nero demanded a courtier throw a banquet in his honor and spend no less than four million sesterces on roses. The Historia Augusta, meanwhile, describes how the scandal-magnet Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (known as Heliogabalus) delighted in dropping flower petals over his dinner parties from an overhead trapdoor. His overexcitement led to bigger and bigger payloads and ended with several guests reportedly suffocating under a sweet-smelling tsunami. This episode is immortalized in a painting by the nineteenth-century artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who emulated the decadence of his Roman forebears by having fresh batches of roses delivered throughout the winter from the French Riviera so that he could better capture their plushness.

Victorian authors were obsessed by the notion that roses were indecently heady. Swinburne, for example, contrasted the “lilies and languors of virtue” with the “raptures and roses of vice.” Rooms that witness scenes of sultry indulgences and untamable passions are decorated with roses in the writing of Émile Zola and Oscar Wilde.

Tales of the decadent Romans and their mania for roses influenced all these nineteenth-century writers and artists. But they were also enthused by the courtly literature of the Middle Ages, particularly the “Roman de la Rose” of 1275, written by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun. This strange poem describes a “Dream Lover” and his quest to possess an alluring, delicately scented and voluptuous rosebud. He spies it in a walled garden, but it is tantalizingly out of reach. After a series of fantastical misadventures and the authors’ various scholarly digressions, the protagonist finally encounters the alluring flower. The clinching episode is a scantly veiled allegory of sexual conquest, the author bragging:

This much more I’ll tell you: at the end,

when I dislodged the bud, a little seed

I spilled just in the center, as I spread

The petals to admire their loveliness,

Searching the calyx to its inmost depths.

The poem was incredibly popular in its day and its influence spread across Europe like a lava flow, enflaming readers in their thousands. But the work had two formidable critics: the church and a certain French female poet.

The “Roman de la Rose” was an affront to the Christian church because they had a separate tradition of symbolism for roses that had taken hold a thousand years before the poem had been penned. Ambrose of Milan, writing in the fourth century AD, described the rose as the flower of paradise, and the Virgin Mary as a “rose without thorn.” Later writers, including Bernard of Clairvaux, perpetuated this image. It inspired a tradition in art of depicting Mary surrounded by roses, or suggesting her presence with a single rose, as the Spanish artist Zurbaran did with such understated grace in the seventeenth century. The holy significance of roses is further manifested in artifacts like rosary beads and the “Golden Rose” of the Pope, which is blessed annually on the fourth Sunday of Lent and periodically awarded to a worthy recipient.

In February 1402, Christine de Pizan — reputed to be the first woman to earn her living through writing alone — was completing a series of letters decrying the influence of the “Roman de la Rose.” She was dismayed by the cocksure, objectifying masculinity of the poem. She believed it to be a manifesto of misogyny, showing men treating the opposite sex as a passive commodity to be hunted and possessed without consent, utterly corrupting the rose’s Christian symbolism.

So, the same year, de Pizan completed a poetic riposte titled “Le Dit de la Rose.” Like the “Roman de la Rose” it also described a dream vision. But here she imagines a chivalric order of knights who, rather than exercising their male privilege to plunder what they desire, give their sweethearts a rose with honor, without assuming reciprocation. Unlike the earlier poem, De Pizan’s describes the dream occurring on Valentine’s Day. This would have been seen as a fashionably modern point of reference, as Valentine’s Day had been nominated as the day of love only twenty years earlier by Geoffrey Chaucer in his 1382 poem “Parliament of Fowls.”

De Pizan would go on to write further tracts proclaiming the rights of women, including The Book of the City of Ladies which describes the construction of a mental citadel by and for women under the tutelage of justice, reason and righteousness. Her writing is seen as an important precursor to feminism, but her other accomplishment was to make what is probably the earliest recommendation to send roses to your sweetheart on February 14.

She rescued the flower’s reputation, transfiguring it from a symbol of decadence, excess and carnal desire into one of chivalric decency. Out of prurience came purity: the Valentine’s Day rose was born.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.