This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

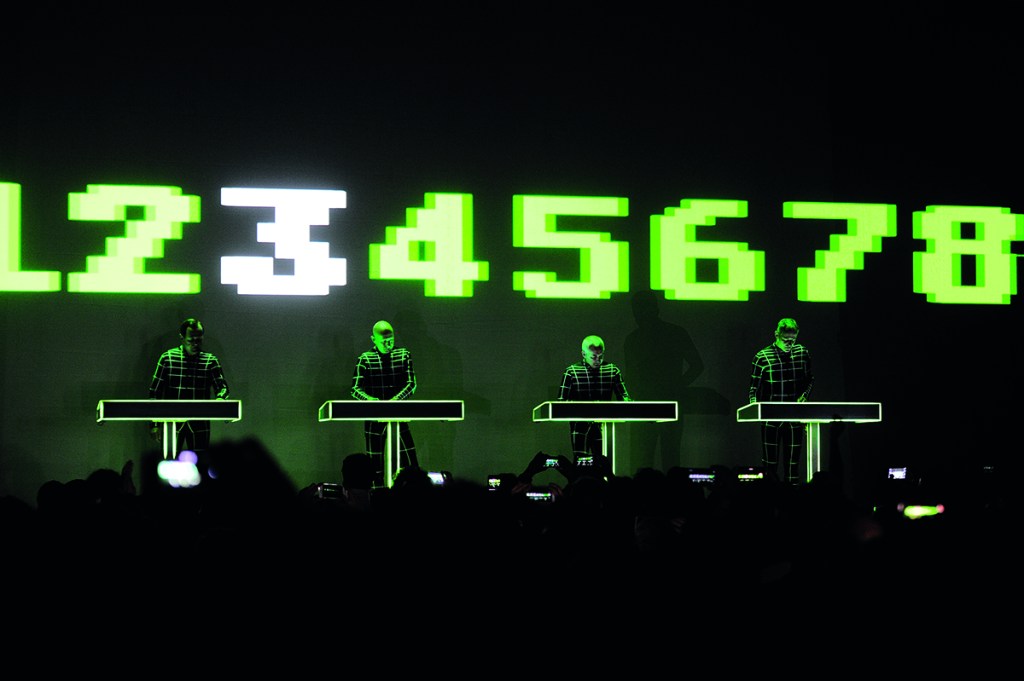

Right from the beginning, everything about Kraftwerk was odd. They had no frontman, they seemed to play no instruments and their strange, electronic music owed nothing to blues, soul or any of the other forms of music that underpinned 20th-century pop. Instead, a Kraftwerk gig consisted of four gauche-looking fellows from Düsseldorf standing in a row, each poking at a synthesizer while strange, apparently unconnected images appeared on screens behind them.

A Kraftwerk album could be just as confounding. The cover of 1977’s TransEurope Express featured the band in suits and ties, looking more like the partners at an accounting firm than a pioneering electronica band.

Odd they may have been, but Kraftwerk were revelatory for being the first group in history to make purely electronic music. Their sound, a torrent of synth tones, drum machines and electronically mangled voices, was so different as to be almost alien. Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, who met in 1968 and founded the band in 1970, called their sound industrielle Volksmusik, which David Bowie, a big fan, translated as ‘folk music of the factories’.

Perhaps the most surprising thing of all about Kraftwerk was that the band turned out to be a colossal success. Autobahn, their fourth album, should by any reckoning have been a commercial disaster when it was released in 1974. The first side comprised a single track, nearly 23 minutes long, about the joy of German motorways. The cover art was, you guessed it, a motorway sign. Almost unbelievably, the album went to number five on the Billboard chart and stayed on the chart for more than four months.

Stranger still was the resonance that Kraftwerk’s rather buttoned-up European style had with black communities in the United States. The crossover between Kraftwerk and hip hop is an intriguing one, shining a revealing light on both strains of music. Postwar German artists were set on creating new forms of expression in order to escape their country’s tainted history. Similarly, black American artists were also looking to move beyond their own deeply troubled past. It was this search for the new that made Kraftwerk so appealing not only to hip hop artists such as Afrika Bambaataa and Run-DMC, but also to Prince, George Clinton and the enormously influential Detroit techno scene, whose music returned to the land of Kraftwerk’s birth as house.

It was 1978’s The Man-Machine that won Kraftwerk a global reputation. This brilliantly conceived work included ‘The Model’, the single that went to number one worldwide. It also presented the most famous image of the band, as a four-piece of strange, automaton-like figures, dressed identically in red shirts, black ties and dark trousers. It was a daring move for a German group to present itself as a cadre of robotic, uniformed young men dressed in black and red. The Nazi association was subtle but unmistakable.

Of course, Kraftwerk had no Nazi sympathies. As much as it was a band, Kraftwerk was an intellectual project, an idea born of the conceptualist art movements of the 1960s and strongly influenced by Karlheinz Stockhausen, the German composer who had first used electronic sounds in the 1950s. The flirtation with forbidden imagery was a signal, a warning of the dangers of conformity, but also an indication the band dared to reach back into Germany’s past for its inspiration. As Hütter explained, ‘Our roots were in the culture that was stopped by Hitler; the school of Bauhaus, German Expressionism.’ Kraftwerk’s ambition, then, was nothing less than a re-animation of German culture.

Their aim was to achieve this through the creation of what Wagner called the Gesamtkunstwerk — the ‘total work of art’. For Kraftwerk, the music, graphics, artwork, outfits and videos were parts of a whole. It was a lesson the band had also learned from Warhol: pop culture had to transcend the dividing lines between the various art forms.

But of all the divides they broke down, the most significant was that between musician and sound engineer. Kraftwerk popularized the idea that not only a musical instrument could be played: the mixing desk itself could be an instrument. Kraftwerk, in their synth-lined Kling Klang studio (no visitors allowed), were the first producer-artists of an era when electronic sounds became dominant, in a line stretching from Quincy Jones to Dr Dre to house music, all the way through to the current proliferation of bedroom-laptop wannabes.

As this strange, slightly jumbled, rather intense book notes, ‘music is the movement of sound through time’. It’s a good line. As the music of the 20th century fades from our ears, Kraftwerk’s sound is still moving.

This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.