In early October 2021 President Joe Biden, the CIA director William Burns and other top members of the US’s national security team gathered in the Oval Office to hear a disturbing briefing from US military chief General Mark Milley. “Extraordinary detailed” intelligence gathered by western spy agencies suggested that Vladimir Putin might be planning to invade Ukraine. According to briefing notes that Milley shared with the Washington Post, the first and most fundamental problem facing Biden was how to “underwrite and enforce the rules-based international order” against a country with extraordinary nuclear capability “without going to World War Three.” Milley offered four possible answers: “No. 1: Don’t have a kinetic conflict between the US military or NATO with Russia. No. 2: Contain war inside the geographical boundaries of Ukraine. No. 3: Strengthen and maintain NATO unity. No. 4: Empower Ukraine and give them the means to fight.”

As the first anniversary of Putin’s disastrous invasion approaches, the US has pushed all four of its own red lines to their very limits. The war remains geographically contained, but the Russian foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, in December accused the United States and NATO of playing a “direct and dangerous role” in the war, just a shade short of declaring NATO an actual combatant. NATO remains largely united, though cracks are appearing in the alliance. Croatia’s president, Zoran Milanović, recently announced that he was “against sending any lethal arms [to Ukraine] as it prolongs the war” and called the West’s support for Kyiv “deeply immoral because there is no solution.” Ukraine’s army is now better equipped than those of most NATO members, but it is struggling to contain Russian advances in the Donbas and could suffer badly from an early spring offensive.

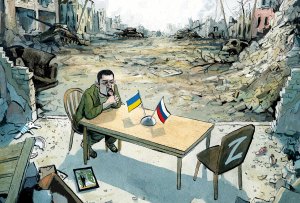

So as the West crosses the Rubicon of supplying battle tanks to Kyiv, it’s worth revisiting Milley’s first and most pressing conundrum — how to avoid the Ukraine conflict turning into a world war. And worth considering, realistically, the various scenarios for the war’s end.

The Ukrainian victory scenario is clear-cut: to expel Russian troops from every inch of its territory, including Crimea and the self-proclaimed Donbas “republics” annexed by Russia. Some Kyiv officials have also spoken of forcing Russia to pay reparations and putting its commanders — up to and including Putin — in the dock of an international war crimes tribunal.

But this has not always been Zelensky’s position. In the early days of the war, as well as during several rounds of failed negotiations between Moscow and Kyiv that were brokered by the Turks in March and April, Zelensky broadly hinted that both full NATO membership and the status of Crimea and Donbas were negotiable, subject to internationally supervised plebiscites after a withdrawal of Russian troops to pre-February 24 borders (which would probably have left Crimea under Russian control).

In retrospect, that was a deal that Putin should have taken. But the talks broke down because of Russian arrogance and intransigence, because Ukraine was starting to win tactical victories on the battlefield, and, perhaps most importantly, because the West’s groundswell of military support allowed Zelensky to abandon his early pragmatism — born of weakness — and shift to a maximalist position that was morally clearer but politically and militarily riskier.

According to Gideon Rose, author of How Wars End, every war ever fought has had three phases: the opening attack, the struggle for advantage and the endgame. That endgame inevitably has one of two outcomes: either the tide of war turns irreversibly in one side’s favor, like the Allied victories in 1918 and 1945, or the conflict ends in some kind of mutually agreed peace — at best a negotiated one, like that between Egypt and Israel in 1973, at worst an exhausted stalemate, like in Korea in 1953 or Cyprus in 1974.

The war in Ukraine is currently still in its middle phase: the struggle for advantage. Neither Russia nor Ukraine is interested in negotiating because each side is still either trying to win outright, or at the very least enhance its position on the battlefield and thus have a stronger position from which to eventually make peace terms. NATO’s top European leaders have come into line with the US position of supplying offensive arms to Kyiv. Even the German chancellor, Olaf Scholz — who before the invasion was willing to send nothing more deadly to Kyiv than a shipment of 5,000 helmets — has finally agreed to send Leopard 2 battle tanks.

But dig a little deeper into this apparent allied unity, and a clear gulf emerges between NATO’s vision of victory and Ukraine’s. Zelensky insists that Crimea must be retaken to restore the territorial integrity of Ukraine. Prominent western commentators such as the retired lieutenant-general Ben Hodges, former commander of the United States army in Europe, insist that seizing Crimea is “strategically vital” for Ukraine’s future military security. But it’s also clear that the fight to take back Crimea and the former rebel republics of the Donbas will entail fighting a very different kind of war. Instead of liberation, it will be a war of conquest. Russia’s 2014 annexation of the Crimean peninsula was clearly illegal and the subsequent referendum where 97 percent of voters chose to join the Russian Federation was far from free or fair. But it’s equally clear that a significant majority of those living in Crimea now are Russians who do not wish to be Ukrainian.

The situation in the rebel republics of the Donbas is less clear-cut — not least because of massive de facto ethnic cleansing that has seen up to two-thirds of the pre-war populations of the Donetsk and Lugansk Peoples’ Republics leave, both for Ukraine and Russia. But Anne Nivat of France’s Le Point, one of the few independent western journalists to visit Russian-controlled Donbas at the end of last year, tells me that she “did not meet anyone wanting to rejoin Ukraine.” That tallies pretty closely with my own reporting in Donetsk and Lugansk (Luhansk in Ukrainian) back in 2014 — those people sympathetic to Kyiv had been bullied and terrorised into fleeing, while those who remained were more or less uniformly anti-Ukrainian. The male populations of the rebel republics have been ruthlessly conscripted en masse, and poorly equipped Donbas locals — some of whom were photographed going into battle with 1930s-pattern Mosin rifles — have made up much of Russia’s cannon fodder. Whether their shed blood makes them and their loved ones more or less sympathetic to Kyiv remains to be seen, but a recent New York Times report highlighted divided loyalties even among the locals of Kherson and parts of Donbas liberated by Kyiv’s troops.

That raises a very uncomfortable question — does the West want to be in the business of coercing people to rejoin a nation they don’t wish to be part of? In Ukraine, the subject was taboo even before the war. Zelensky’s first foreign minister, Vadym Prystaiko, now Ukraine’s admirable ambassador in London, was sacked after suggesting the future of the Donbas should be left for the locals to decide.

The tragedy of this war is that there is no equitable or safe solution. To formally cede control of parts of Donbas and Crimea to Putin would reward aggression and create a massive moral hazard. It would leave Ukraine with no natural or defensible border, and would leave a Kremlin regime in power that remains a clear danger to Kyiv and its neighbors. Conversely, supporting Ukraine’s advance to its 1991 borders would entail backing what the local population would see as a coercive war of conquest. More seriously, the loss of the Donbas and Crimea would — certainly if Russian history is anything to go by — be as fatal to the Putin regime as the defeat in the Russo-Japanese war, World War One and Afghanistan were to the czars and to the USSR. Many Ukrainians, for painfully obvious reasons, would welcome exactly that, as would many of Kyiv’s supporters in the West. But a cornered, collapsing, nuclear-armed Russia would risk precisely the Armageddon scenario which the US has been at such pains to avoid.

The Biden administration’s compromise solution has been to steadily grind down Russia’s military while not provoking a direct confrontation between the Kremlin and NATO, at the same time working to keep sceptical members on board. But Hungary, Austria and Croatia remain defiantly opposed to sending more military hardware; the Italian right is deeply split; and there have been sporadic anti-war demonstrations in Germany and the Czech Republic. Not to mention a small but vocal caucus in the US Republican Party led by the firebrand Georgia congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, who said in November that “under Republicans, not another penny will go to Ukraine… our country comes first.”

Putin, for his part, still has massive reserves of men and low-tech arms to throw into the conflict even as his arsenal of high-precision rockets runs low. While the main constraint on Kyiv’s war effort is material, the Kremlin’s main concern is political. Further mobilization is risky for Putin, but by no means fatally so. And in a military contest between quality and quantity — Kyiv’s superior morale, discipline, training and equipment versus Moscow’s Soviet-style steamroller might — unfortunately there comes a point where quantity wins. That is why Putin is by all accounts preparing a major offensive, probably from several directions, to build on recent bloody advances around Soledar and create a tactical advantage on the ground before western tanks can be deployed and their Ukrainian crews. Russia cannot hope to win this war, but it still has a fighting chance of not losing it.

Zelensky is also in a far more precarious position than his current popularity suggests. He has promised his people total victory, and polls say that close to 90 percent of voters believe him. Failing to deliver would be politically fatal. So would signing any peace deal that involves a loss of Ukrainian land. That will, almost inevitably, put Zelensky and his western backers on a collision course. If Putin advances, then announces a ceasefire and calls for talks, the NATO alliance will immediately split between those members who want justice and those who want peace. That won’t, in itself, stop Ukraine from fighting on. But it’s NATO which has its hand on the throttle of materiel, and a potential forever war will test the resolve even of Ukraine’s staunchest allies. Even the optimistic scenario of forcing the Russians back to pre-invasion borders would still leave Ukraine dismembered and Putin probably still in power. Tragically, there is almost no realistic outcome for this war that will not end in the Ukrainians crying “Betrayal!” But if the alternative would be fighting World War Three, that may end up being the least bad option.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.