By the time you read this piece, Prince Harry’s autobiography Spare will have been published in the United States. The question of whether it’s any good will be decided swiftly by the newspaper and online literary critics, but we in the monthly magazine trade have, alas, been denied the opportunity to see it before our publication deadlines. Under normal circumstances, this would bode very badly indeed. As with films that are not screened for critics beforehand — “because we want the audience to discover the magic for themselves” — books that have very tight publication schedules and are embargoed to the hilt are usually seen as flops-in-prospect. Add the strange decision not to release Spare in time for the lucrative Christmas market, and the book might seem to have all the makings of a turkey, rather than the golden goose its publisher Penguin Random House hopes that it will be.

But — and I am writing this sight unseen, so I might be deeply embarrassed by the time this issue is published — there are grounds to be cautiously optimistic about the book. Prince Harry’s choice of ghostwriter in J.R. Moehringer is a good one: not only did Moehringer work wonders with Andre Agassi’s memoir Open — he certainly likes his meaningful single-word titles — he is a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer whose own autobiography, The Tender Bar, was filmed by George Clooney (a close friend of the Sussexes) and explored the complexities of father-son relationships, just as Open did. It is inevitable that Spare will concentrate on Harry’s father, now King Charles III; it will presumably shed light on what is said to be a troubled and combative relationship, although distinguishing hearsay and gossip from documentable fact will be a difficult task for both Moehringer and the book’s named author.

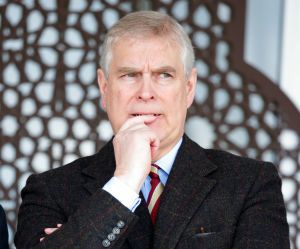

There has been scuttlebutt about Spare in both the British and American media for months. It has been suggested that Harry reserves especial resentment for Camilla, the queen consort, because he blames her primarily for destroying his parents’ marriage: given that Camilla, aided by some skillful PR, is generally regarded as popular and accessible and an asset to the royal family, it will be interesting to see whether this is made explicit in the finished book, subtly alluded to, or omitted altogether. Likewise, Harry has apparently been told that, in the wake of the Queen’s death and the forthcoming coronation of his father in May, he’d better have toned down the most incendiary material or expect to be cast out of “the Firm,” joining his Uncle Andrew in reputational Siberia.

The question is not so much whether any of this is true, but whether Prince Harry cares any longer. Ever since he and his wife staged their quasi-abdication from the royal family at the beginning of 2020 — just in time for lockdown! — he has been transformed from the good-hearted playboy prince of tabloid speculation to a furious figure, railing against his family’s mistreatment of him and his wife to anyone who will give him a platform.

Given that companies have been lining up to get into bed with them both (figuratively speaking), there is little doubt that Spare will enjoy a marketing boost that most other authors could only dream of: Netflix, Spotify and Penguin Random House are a formidable multinational trio, and undoubtedly others will make themselves known in due course, queuing up to take a piece of the royal dollar. Because make no mistake, ladies and gentlemen, Britain’s royal family sells books like nobody’s business. Dead or alive, stick a king, queen, prince or princess on the front of your title, and watch the sales roll in. Easy money, isn’t it?

Not exactly. The problem with writing about the royals is that it is a spectacularly well-trodden path. Unless one wishes to explore, say, the life of Princess Maud of Wales, the difficulty is that the story a royal biographer wishes to tell has been written about countless times before. A cursory search for “Elizabeth II biography” throws up literally thousands of books, ranging from serious, in-depth titles written by historians with decent access to archives and sources and an innate knowledge of the period to the cheapest and most tawdry of cash-ins that recycle the same hoary anecdotes known to anyone with even the most passing interest. And then there are the children’s titles, the picture books, the self-published erotica…

Perhaps not the last category. But where Harry is marking new ground for himself — or at least, ground not trodden for seventy years — is in being a member of the Firm who is publishing his own memoir. While many royals have dabbled in writing themselves (King Charles has released everything from children’s books to A Vision of Britain, a book about contemporary architecture, and the Duchess of York is now making a living writing romance novels for the imprint Mills & Boon), few have ever gone against the family’s unofficial motto of “never complain, never explain” and released their own cri de coeur. There is, as ever, one major exception to this, and that comes in the dapper form of the former Edward VIII, latterly the Duke of Windsor.

As someone who is currently writing his third work of narrative nonfiction with the duke as a major character, I can confidently report that he is the gift that keeps on giving. His letters hum and seethe with petulance and rage; his public antics become increasingly tawdry and pathetic, as he becomes obsessed by chasing dollars at all costs, dignity be damned; and his relationship with Wallis Simpson, much pored-over by gossipmongers and serious historians alike, is a fascinatingly complicated one many have compared to a similar dynamic between the Duke and Duchess of Sussex. All this is as may be, but the Duke of Windsor is especially intriguing in that he is the only member of the royal family to have published a tell-all memoir. Until now, that is.

A King’s Story was first published in the United States on April 14, 1951, to universal acclaim. Stephen Spender’s review in the New York Times the next day went so far as to compare Edward’s downfall to that of Byron and Wilde, and suggested that, in his “important and highly interesting book,” the duke had redeemed himself in the public eye, even if the saga remained “on the level of serious comedy rather than tragedy.” Spender, perhaps not entirely au fait with the wider details of the duke’s relationship with his family, wrote that the abdication crisis — “a situation pregnant with disaster” — had “ended with comparative happiness all round.”

This was a very generous assessment. The duke, in collaboration with the ghostwriter Charles Murphy, had produced a book that had to be toned down because of the ferocity of its attacks on his enemies, not least his brother George VI, who was extremely ill with the lung cancer that would kill him only months after it was published. Heeding the advice of such friends as Winston Churchill and the newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook, the duke produced a gossipy, acid memoir that happily laid into old foes such as the former prime minister Stanley Baldwin and the Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Lang, and, even if it avoided a full-frontal attack on his own family, featured enough barbed remarks to make him extremely unpopular with the Firm forever after. If, of course, he hadn’t been persona non grata already.

It remains to be seen whether Spare has the same incendiary effect as A King’s Story. The current Harry and Meghan series on Netflix, which was much-anticipated for months, has ended up being something between boring and tawdry, and there is the possibility that audiences turned off by that will lose interest in yet another tell-all book that repeats many of the same stories. Or it is possible that it will be as jaw-dropping as his Uncle Andrew’s notorious BBC Newsnight interview, and that it will damn his reputation forever. Still, I can rest assured in one regard: whatever happens with Spare, it will not represent the end of this particular saga. After all, his wife has to write her memoir next, and then the fur will truly fly.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.