At first glance, nostalgia does not seem like a subject much suited to exploration via the medium of the pop song; after all, this is the topic which inspired, at least in part, Ulysses and À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, two of the greatest and longest novels of the 20th century. What can one say in three minutes that hasn’t already been said in six volumes?

On the one hand, we have such warnings from history as ‘Those Were the Days’ by Mary Hopkin or Terry Jacks’s implacably awful ‘Seasons in the Sun’, a rendition of Jacques Brel’s ‘Le Moribond’ which loses not just something but everything in translation. On the other hand, during the 1980s both The Smiths and Pet Shop Boys looked back on their lives, often with a sense of shame, to melancholy yet memorable effect: ‘Back to the Old House’, ‘Cemetry Gates’, ‘This Must Be the Place I Waited Years to Leave’. Ah the 1980s, the good old days when bands really knew how to write nostalgic songs.

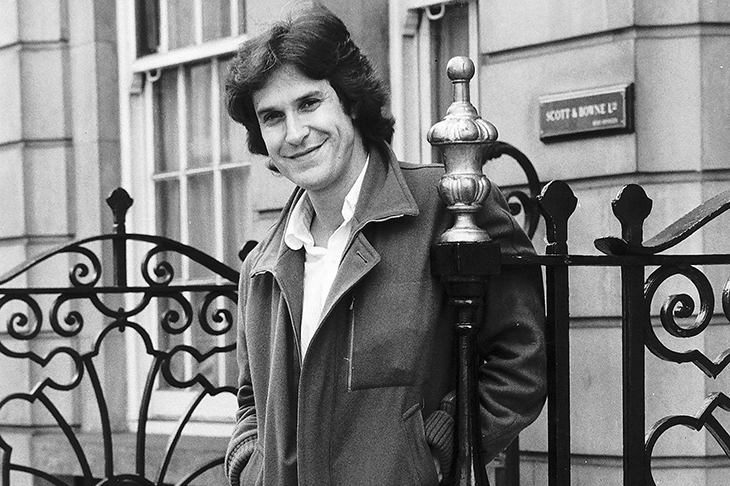

In fact, the great pioneer of looking back — in three minutes or under — was Ray Davies, the chief singer and songwriter of the Kinks. Only 20 when the Kinks topped the charts with ‘You Really Got Me’ in 1964, Davies grew increasingly preoccupied with nostalgia when all around were raving in discotheques or fighting in the streets: ‘Where Have All the Good Times Gone’; ‘Autumn Almanac’; ‘Do You Remember Walter?’; ‘The Way Things Used to Be.’

The Kinks’ 1968 single ‘Days’ and LP The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society are the summit of this theme and arguably the group’s artistic peak, a magical collection of songs which deal explicitly with the bittersweet lure of the past. In 1975 Davies wrote a lyric in which he told himself to snap out of it, ‘No More Looking Back’, but to little avail; a few years later ‘Come Dancing’, a paean to the lost dance halls of Davies’s youth, proved to be the Kinks’ last big hit.

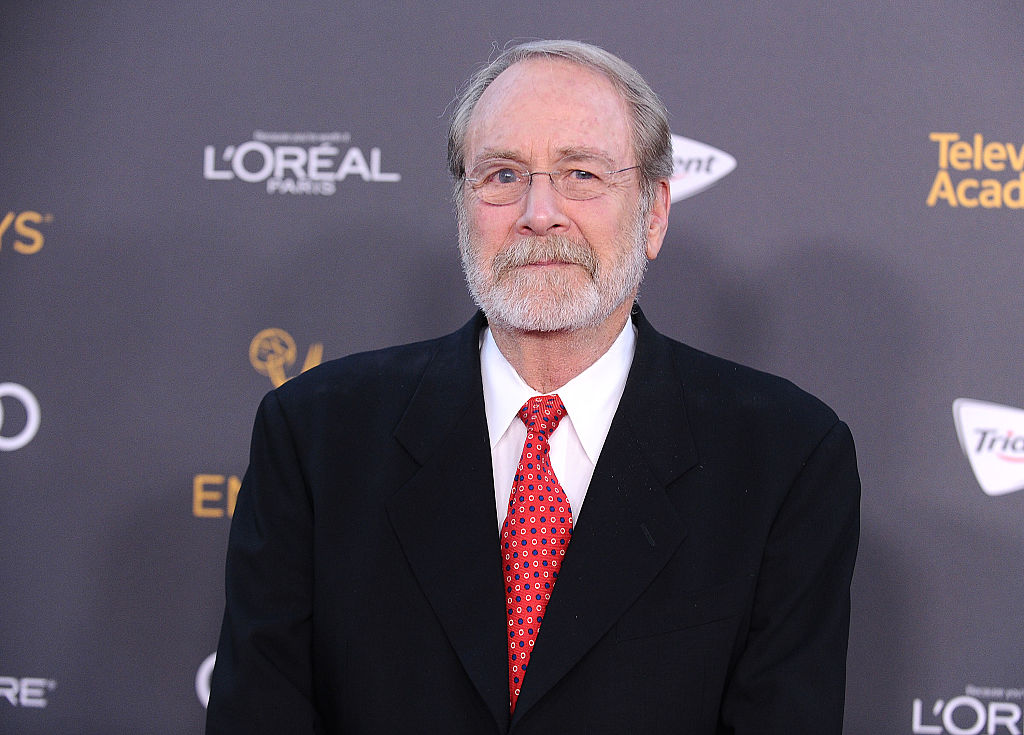

Here in 2020, writing about the Kinks — about any of the groups of the 1960s —is increasingly a nostalgic act, a paean to a lost world of hit parades, Top of the Pops, the Beatles v. the Stones, albums and singles, the dwindling ecology of pop music as it once was. As a series of 80th birthdays and 60th anniversaries hove into view in the decade ahead, what until recently still felt like celebration is beginning to assume the quality of commemoration. They are knighting the survivors, among them Sir Ray Davies. So it is to Mark Doyle’s considerable credit that in this book he succeeds in making the Kinks’s records, these historical recordings from a bygone era, seem brand new, fresh and relevant; and he does so by recreating the past.

In Songs of the Semi-Detached, Doyle’s approach is to isolate key phases of both Davies’s songwriting and the Kinks’ recording of those songs, a significant distinction, and build up the personal, social and historical context around each of them. ‘Although the Kinks had deep roots in a particular social milieu (postwar working-class north London) and participated in a distinctive cultural moment,’ he writes in the introduction, ‘they were never fully a part of either world.’

This point is crucial to understanding the Kinks fully; although at this distance one might be tempted to believe that, like the Beatles in their second feature film Help!, all the big pop groups lived in adjoining houses in the same street, Ray and his younger brother Dave were not like everybody else. Moreover, they knew it (and wrote a song about it). It is this sense of partial detachment that Doyle identifies as the thread running through all the styles Davies, via the Kinks, would adopt between 1964 and 1971: rocker, satirist, pop anthropologist, nostalgic and social commentator. The author concludes that each of these phases, from ‘A Well-Respected Man’ to ‘Sunny Afternoon’ to the album Muswell Hillbillies, was the product of Davies’s working-class upbringing and what he perceived as a variety of threats to that world:

‘He is worried about what has happened to the tight-knit community that reared him, pessimistic, as always, but not without hope. He borrows liberally from his own past and that of his family, appropriates musical styles long out of vogue, sings like an old man, sounds jocular when he’s actually sad, sounds sad when he’s actually uncertain and explores decidedly unfashionable topics like slum clearance and air pollution.’

The result is a book that distinguishes between the musical and lyrical conservatism of which Davies has been accused and the ambivalence and compassion which informs his best songs. I know these records inside out, but Doyle sent me back to them with fresh insights and enthusiasm. He frames The Village Green Preservation Society, for instance, as Pop Art rather than anthems of ‘Little England’; he presents Arthur as a song cycle, the roots of which lie in suburbia, the small pleasures, aspirations and frustrated dreams of its inhabitants.

There are more straightforward accounts of the Kinks’s career available, including some by members of the group, but few are as eloquent, persuasive or fully engaged as Songs of the Semi-Detached.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.