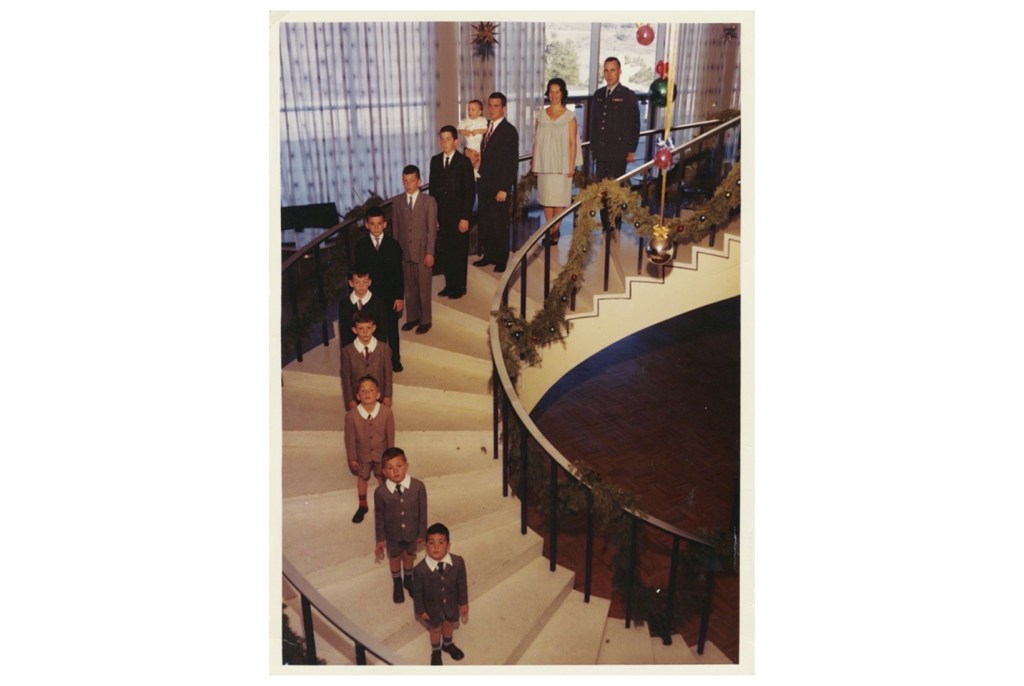

Don Galvin and Mimi Blayney married in December 1944. It was a shotgun wedding. They had been high school sweethearts. Just before Don was about to be shipped out to join the fighting in the South Pacific, Mimi called from New York to say she was pregnant. A rushed wedding across the Mexican border in Tijuana followed: a not uncommon wartime story. But Mimi’s pregnancy turned out to be the first of a dozen, each accompanied by severe morning sickness. Between 1945 and 1965, a procession of children arrived, ten boys and then, at last, even after Mimi’s gynecologist had warned that further pregnancies might prove life-threatening, came two girls.

Don had remained in the Navy after the war, but his career stalled. Perhaps, Robert Kolker suggests, his dalliance with an admiral’s wife may have had something to do with that. It would not be the handsome Don’s last affair, though his philandering remained hidden from his children for many years. Leaving his failing Navy career in 1950, Don joined the Air Force, which had just been established as a separate branch of the armed services. His ever-increasing family would spend most of their childhood in Colorado Springs, at the new Air Force Academy, where Don became a public relations flack and instructor, before moving to a career in the non-profit sector, overseeing federal grants to several western states.

Hidden Valley Road centers around a meticulous reconstruction of the lives of the Galvin parents and children. The family history Kolker provides is remarkable for its depth and for the sympathetic portrayal of a large cast of characters, each of whom is sketched with great skill. To accomplish this feat, the author spent years interviewing family members, their relatives, friends and acquaintances. He pored over family documents and photographs, and read voluminous case records of the many individuals’ encounters with the medical profession. And that last set of materials provides the clue to what would otherwise be a puzzling question: what drew Kolker to the Galvin family and prompted him to immerse himself so obsessively in their lives? It was a disturbing secret that Don and Mimi long sought to conceal from the world: six of their 10 sons went mad and ended up being diagnosed as schizophrenic.

The boys’ madness surfaced with full force as each of them reached adolescence. Don absented himself as much as possible from the toxic atmosphere that ensued, burying himself in work (and perhaps in affairs). Mimi tried to ignore what was happening around her and to pretend that domestic life was somehow under control and ‘normal’; but the degrees of mental disturbance the young men exhibited were extraordinary, and eventually impossible to conceal from the outside world.

Donald, the eldest, wandered naked around the house, hallucinating and voicing a variety of religious delusions. Later on, when Mimi couldn’t confine his disturbed behavior within the house, he became the first of the boys to be institutionalized. Here, his clinical records reveal that he was ‘assaultive, destructive, belligerent, suicidal, hyperactive, over-talkative and grandiose’.As soon as large doses of drugs sedated him sufficiently, he was released back to his family, just as his equally disturbed brothers would be. The revolving door is a central feature of the ‘management’ of mental illness at the time.

Jim, the second boy, secretly molested at least one of his brothers, and then raped his sisters. (He may have been prompted down this pathway by the Catholic priest who had arrived to convert his mother to the faith and, treated as a family friend, proceeded to sexually abuse more than one of the boys.) Still another son, Brian, would eventually shoot his wife and then turn the gun on himself, a murder-suicide that haunted one of the few brothers who emerged from this house of horrors to enjoy some semblance of a normal life — though, as one might imagine, no one survived this upbringing without incurring deep emotional scars.

Kolker’s reconstruction of this nightmarish perversion of suburban family life is extraordinarily well done. It reminded me in many ways of the portraits drawn by Andrew Solomon of out-of-the-ordinary children and their families in Far from the Tree (2012). But Kolker wants to do more than merely provide a family history that reads like a series of gothic horror stories. He also explores the evolving views of psychiatrists on the nature and etiology of schizophrenia, and discusses the treatments they administered to the Galvin sons.

These sections of the book, while valuable, strike me as insufficiently thought through and sometimes seriously deficient. Kolker mentions the Freudian attempts to attribute schizophrenia to refrigerator mothers and ineffectual or absent fathers; and though there is much in his description of Galvin family life that suggests a deeply pathological environment, he dismisses these theories as victim-blaming. Certainly, he faced an almost impossible task when it came to disentangling whether the family environment was productive of pathology, or the pathology of the domestic scene was the product of coping somehow, anyhow, with extraordinarily difficult circumstances.

Periodically, Kolker notes that the drug and shock treatments that later became psychiatry’s stock response to schizophrenia were of dubious efficacy and may have worsened the sons’ problems. Almost certainly that was true. The men became obese, exhibited the symptoms of Parkinsonism and other movement disorders, and in some cases became diabetic and developed heart problems — all known complications of antipsychotic medication.

Drugs and ECT at best rendered them somnolent and inactive, and were administered cavalierly. Peter, for example, was simultaneously on eight different drugs — Geodon, Risperidone, Neurontin, Risperdal Consta (an injectable drug), Zyprexa, Prolixin, Trileptal and Thorazine — and when those failed to calm him was given ECT once a week. (Bizarrely, Kolker claims that ECT ‘seems to be able to adjust serotonin and dopamine levels more effectively than any medication’, an assertion for which there is zero scientific evidence.)

Two other brothers were given the extremely dangerous though sometimes effective drug Clozapine, and not properly monitored. Both subsequently died from neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a recognized side effect of the treatment. These issues, and the more general deficiencies of psychiatry in the closing decades of the 20th century, should have been highlighted and discussed more thoroughly than Kolker manages to do.

Finally, he uncritically embraces some fringe notions about the genetic origins of schizophrenia. That six of the 12 children became mentally ill obviously attracted the attention of researchers who sought to explain schizophrenia as the product of genetic defects. But research in this area has proved extraordinarily frustrating, and periodic claims to have discovered the Holy Grail have repeatedly failed the test of replication.

Few now believe that there is a single gene for schizophrenia, and many have doubts that there is a single disorder gathered together under that name. (It is worth reminding ourselves that the man who invented the term, Eugen Bleuler, spoke of ‘the schizophrenias’.) Yet Kolker spends large portions of his book promoting the notion that two researchers he encountered along the way may have uncovered ‘the gene’ that explains much of the pathology — though each points to a different abnormality and neither has persuaded the larger scientific community that he or she has discovered the ‘germ of madness’.

The infatuation with these two scientists is distinctly odd, not least because Kolker elsewhere acknowledges that the most comprehensive recent review of the genetics of mental disorder, which compared a vast amount of data from a host of schizophrenic patients, failed to unmask a clear suspect or suspects. Myriad suspicious genetic variants were investigated. ‘Each of these genetic irregularities, taken by itself, accounted for a minuscule increased chance of an individual having schizophrenia.’ Even taken together, these genetic markers ‘would only increase one’s chances of having the disease by about 4 per cent’.

I can only conclude that for someone who has witnessed so much pathology and unhappiness, the urge to believe that a miracle cure lurks just around the corner is irresistible. But, sadly, it remains a pious hope, not our present reality. We live in a world where the problems of coping with the grave disruptions that serious mental illness brings in its wake fall squarely on the shoulders of families, if the patients in question are not simply abandoned to the gutters and the gaols. And Kolker has given us an exceptional and moving dissection of what this means for those forced to live with the depredations of madness.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.